Summary

The domed Mauritius giant tortoise (Cylindraspis triserrata) is an extinct species of giant tortoise. It was endemic to Mauritius.

| Domed Mauritius giant tortoise | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull of Cylindraspis triserrata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | †Cylindraspis |

| Species: | †C. triserrata

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Cylindraspis triserrata Günther, 1873

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Description edit

One of two different giant tortoise species which were endemic to Mauritius, this domed species seems to have specialised in grazing of grass, as well as fallen leaves and fruit on forest floors. Its sister species was likely a browser of higher branches, and although similarly sized, the two species differed substantially in their body shape and bone structure. The domed species had a flatter, rounder shape, with thinner bones and shell. The species name triserrata actually refers to the three bony ridges on this animal's mandibles—possibly a specialisation for its diet.

Extinction edit

This species was previously numerous throughout Mauritius—both on the main island and on all of the surrounding islets. As Mauritius was the first of the Mascarene Islands to be settled, it was also the first to face the extermination of its biodiversity—including the tortoises. The tortoise species, like many island species, were reportedly friendly, curious and not afraid of humans.

With the arrival of the Dutch, vast numbers of both tortoise species were slaughtered—either for food (for humans or pigs) or to be burned for fat and oil. In addition, they introduced invasive species such as rats, cats and pigs, which ate the tortoises' eggs and hatchlings.

The species was likely extinct on the main island of Mauritius by about 1700, and on most of the surrounding islets by 1735.

Round Island refuge edit

At least one of the two Mauritius giant tortoise species might have survived on Round Island, just north of Mauritius, until much later, according to the 1846 Lloyd report. The Lloyd expedition in 1844 found several very large specimens of giant tortoise surviving on Round Island, although the island was by then already overrun with enormous numbers of introduced rabbits.

In 1870, the Governor Sir Henry Barkly was concerned about the vanishing species and, in his enquiries, was told about the 1844 expedition by one of its members, Mr. William Kerr. Kerr informed the Governor that Mr. Corby, one of the other 1844 explorers, "captured a female land tortoise in one of the caves on Round Island and brought it to Mauritius, where it produced a numerous progeny, which were distributed among his acquaintance."

The Governor was unable to locate any of the progeny and, although hypothetically an 1845 hatchling could easily have lived into the 21st century, it is not known what happened to the hatchlings.

Round Island itself, already badly damaged by rabbits, had goats introduced to it soon afterwards. This—or some other factor—led to the total extinction of the giant tortoises in their last refuge. At the unknown point when the last of Corby's hatchlings died or was killed, the species would have become totally extinct.[3][4][5]

References edit

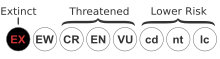

- ^ World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Cylindraspis triserrata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T6064A12390055. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T6064A12390055.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 278. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. ISSN 1864-5755. S2CID 87809001.

- ^ A.Cheke, J.P.Hume: Lost Land of the Dodo: The Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion and Rodrigues. Bloomsbury Publishing. 2010. p.211.

- ^ Cheke AS, Bour R: Unequal struggle—how humans displaced the tortoise's dominant place in island ecosystems. In: Gerlach J, ed. Western Indian Ocean Tortoises: biodiversity. 2014.

- ^ "Non-native megaherbivores: The case for novel function to manage plant invasions on islands". aobpla.oxfordjournals.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2022.