Summary

Mauritius,[a] officially the Republic of Mauritius,[b] is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about 2,000 kilometres (1,100 nautical miles) off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Agaléga, and St. Brandon (Cargados Carajos shoals).[12][13] The islands of Mauritius and Rodrigues, along with nearby Réunion (a French overseas department), are part of the Mascarene Islands. The main island of Mauritius, where the population is concentrated, hosts the capital and largest city, Port Louis. The country spans 2,040 square kilometres (790 sq mi) and has an exclusive economic zone covering 2,300,000 square kilometres (670,000 square nautical miles).[14]

Republic of Mauritius | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Stella Clavisque Maris Indici (Latin)[1] "Star and Key of the Indian Ocean" | |

| Anthem: "Motherland" | |

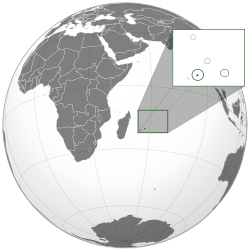

Islands of the Republic of Mauritius | |

Islands of the Republic of Mauritius labelled in black; Chagos Archipelago and Tromelin are claimed by Mauritius. | |

| Capital and largest city | Port Louis 20°12′S 57°30′E / 20.2°S 57.5°E |

| Official languages | None (de jure) (de facto)[2] |

| Lingua franca | Mauritian Creole |

| Language spoken at home (2022)[3] |

|

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Mauritian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Prithvirajsing Roopun | |

| Eddy Boissézon | |

| Pravind Jugnauth | |

| Sooroojdev Phokeer | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 12 March 1968 | |

• Republic | 12 March 1992 |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,040 km2 (790 sq mi) (169th) |

• Water (%) | 0.07 |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 1,265,475[6] (158th) |

• 2011 census | 1,235,260[7][8][3] |

• Density | 618.24/km2 (1,601.2/sq mi) (21st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2017) | 36.8[10] medium |

| HDI (2022) | high (72nd) |

| Currency | Mauritian rupee (MUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (MUT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +230 |

| ISO 3166 code | MU |

| Internet TLD | .mu |

It is believed Arab sailors first discovered the uninhabited island, around 975, naming it Dina Arobi.[15][16] In 1507, Portuguese sailors visited the uninhabited island with the island appearing with the Portuguese names Cirne or Do-Cerne on early Portuguese maps.[17] A Dutch fleet, under the command of Admiral Van Warwyck, landed at what is now the Grand Port District and took possession of the island in 1598, renaming the uninhabited islands after Maurice, Prince of Orange. A succession of short-lived Dutch attempts at permanent settlement took place over a century with the aim of exploiting the local ebony forests, establishing a consistent sugar and arrack production using cane plant cuttings imported from Java together with over three hundred Malagasy slaves, before abandoning their efforts.[18] France took the uninhabited island in 1715, renaming the island "Isle de France". In 1810, the United Kingdom seized the island, and four years later, under the Treaty of Paris, France ceded Mauritius and its dependencies to the United Kingdom. The British colony of Mauritius now included Rodrigues, Agaléga, St. Brandon, the Chagos Archipelago, and, until 1906, the Seychelles.[12][13] Mauritius and France dispute sovereignty over the island of Tromelin, as the treaty failed to mention it specifically.[19] Mauritius became the British Empire's main sugar-producing colony and remained a primarily sugar-dominated plantation-based colony until independence, in 1968.[20]

In 1965, the UK split off the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritian territory to create the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT).[21] The local population was forcibly expelled and the largest island, Diego Garcia, was leased to the United States.[22] Ruling on the sovereignty dispute between Mauritius and the UK, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea has ordered the return of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius.[23]

Given its geographic location and colonial past, the people of Mauritius is diverse in ethnicity, culture, language and faith. It is the only country in Africa where Hinduism is the most practised religion.[24][25] Indo-Mauritians make up the bulk of the population with significant Creole, Sino-Mauritian and Franco-Mauritian minorities. The island's government is closely modelled on the Westminster parliamentary system with Mauritius highly ranked for economic and political freedom being listed by the Economist's Democracy Index as the only country in Africa with full democracy.[26] Mauritius is the only African country with a very high Human Development Index, and the World Bank classifies it as a high-income economy.[27] It is amongst the most competitive and most developed economies in the African region.[28] The country is a welfare state. The government provides free universal healthcare, free education up through the tertiary level and free public transportation for students, senior citizens, and the disabled.[29] Mauritius is consistently ranked as the most peaceful country in Africa.[30]

Along with the other Mascarene Islands, Mauritius is known for its biodiverse flora and fauna with many species endemic to the country. The main island was the only known home of the dodo, which, along with several other avian species, became extinct soon after human settlement. Other endemic animals, such as the echo parakeet, the Mauritius kestrel and the pink pigeon, have survived and are subject to intensive and successful conservation efforts.

Etymology edit

The first historical evidence of the existence of the island now known as Mauritius is on a 1502 map called the Cantino planisphere which was smuggled out of Portugal, for the Duke of Ferrara, by the Italian 'spy' Alberto Cantino. On this purloined copy of a Portuguese map, Mauritius bore the name Dina Arobi (likely Arabic: دنية عروبي Daniyah ‘Arūbi or corruption of دبية عروبي Dībah ‘Arūbi).[31][32] In 1507, Portuguese sailors visited the uninhabited island after being blown off course from their route to India via the Mozambique channel. The island appears with the Portuguese names Cirne (a typographical error where the 's' of the Portuguese 'Cisne' (Swan) became an 'r) or Do-Cerne (typo of 'do Cisne' meaning 'of' or 'belonging to the Swan') on early Portuguese maps, almost certainly from the name of a ship called Cisne which was captained by Diogo Fernandes Pereira in the 1507 expedition which discovered Mauritius and Rodrigues which he called ilha de Diogo Fernandes but poorly transcribed by non-Portuguese speakers as Domigo Friz or Domingo Frias.[33] Diogo Fernandes Pereira may have been the first European to sail east of Madagascar island ('outer route' to the East Indies) rather than through the perceived safer route through the Mozambique channel, following the East African shore line.

In 1598, a Dutch squadron under Admiral Wybrand van Warwyck landed at Grand Port and named the island Mauritius, in honour of Prince Maurice van Nassau, stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. Later the island became a French colony and was renamed Isle de France. On 3 December 1810, the French surrendered the island to the United Kingdom during the Napoleonic Wars. Under British rule, the island's name reverted to Mauritius /məˈrɪʃəs/ ⓘ. Mauritius is also commonly known as Maurice (pronounced [mɔˈʁis]) and Île Maurice in French, Moris (pronounced [moʁis]) in Mauritian Creole.[34]

History edit

Early history edit

The island of Mauritius was uninhabited before its first recorded visit by Arab sailors in the end of the 10th century. Its name Dina Arobi has been associated with Arab sailors who first discovered the island.

The Treaty of Tordesillas purported to give the Kingdom of Portugal the right to colonise this part of the world. In 1507, Portuguese sailors came to the uninhabited island and established a visiting base. Diogo Fernandes Pereira, a Portuguese navigator, was the first European known to land in Mauritius. He named the island "Ilha do Cisne" ("Island of the Swan"). The Portuguese did not stay long as they were not interested in these islands.[35] The Mascarene Islands were named after Pedro Mascarenhas, Viceroy of Portuguese India, after his visit to the islands in 1512. Rodrigues Island was named after Portuguese explorer Diogo Rodrigues, who first came upon the island in 1528.

In 1598, a Dutch squadron under Admiral Wybrand Van Warwyck landed at Grand Port and named the island "Mauritius" after Prince Maurice of Nassau (Dutch: Maurits van Nassau) of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch inhabited the island in 1638, from which they exploited ebony trees and introduced sugar cane, domestic animals and deer. It was from here that Dutch navigator Abel Tasman set out to seek the Great Southern Land, mapping parts of Tasmania, New Zealand and New Guinea. The first Dutch settlement lasted 20 years. In 1639, the Dutch East India Company brought enslaved Malagasy to cut down ebony trees and to work in the new tobacco and sugar cane plantations.[36] Several attempts to establish a colony permanently were subsequently made, but the settlements never developed enough to produce dividends, causing the Dutch to abandon Mauritius in 1710.[35][37] A 1755 article in the English Leeds Intelligencer claims that the island was abandoned due to the large number of long tailed macaque monkeys "which destroyed everything in it," and that it was also known at the time as the Island of Monkeys.[38] Portuguese sailors had brought these monkeys to the island from their native habitat in Southeast Asia, prior to Dutch rule.[39]

French Mauritius (1715–1810) edit

France, which already controlled neighbouring Île Bourbon (now Réunion), took control of Mauritius in 1715 and renamed it Isle de France. In 1723, the Code Noir was established to regulate slavery; categorise one group of human beings as "goods", for the owner of these goods to be able to obtain insurance money and compensation in case of loss of his "goods".[40] The 1735 arrival of French governor Bertrand-François Mahé de La Bourdonnais coincided with development of a prosperous economy based on sugar production. Mahé de La Bourdonnais established Port Louis as a naval base and a shipbuilding centre.[35] Under his governorship, numerous buildings were erected, a number of which are still standing. These include part of Government House, the Château de Mon Plaisir, and the Line Barracks, the headquarters of the police force. The island was under the administration of the French East India Company, which maintained its presence until 1767.[35] During the French rule, slaves were brought from parts of Africa such as Mozambique and Zanzibar.[41] As a result, the island's population rose dramatically from 15,000 to 49,000 within thirty years. Slave traders from Madagascar - Sakalava or Arabs - bought slaves from slavers in the Arab Swahili coast or Portuguese Mozambique and stopped at the Seychelles for supplies before shipping the slaves to the slave markets of Mauritius, Réunion and India.[42] Of the 80,000 slaves imported to Réunion and Mauritius between 1769 and 1793, 45 % was provided by slave traders of the Sakalava people in North West Madagascar, who raided East Africa and the Comoros for slaves, and the rest was provided by Arab slave traders who bought slaves from Portuguese Mozambique and transported them to Réunion via Madagascar.[43] During the late eighteenth century, African slaves accounted for around 80 percent of the island's population, and by the early nineteenth century there were 60,000 slaves on the island.[36] In early 1729, Indians from Pondicherry, India, arrived in Mauritius aboard the vessel La Sirène. Work contracts for these craftsmen were signed in 1734 at the time when they acquired their freedom.[44]

From 1767 to 1810, except for a brief period during the French Revolution when the inhabitants set up a government virtually independent of France, the island was controlled by officials appointed by the French government. Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre lived on the island from 1768 to 1771, then went back to France, where he wrote Paul et Virginie, a love story that made the Isle de France famous wherever the French language was spoken. In 1796 the settlers broke away from French control when the government in Paris attempted to abolish slavery.[45] Two famous French governors were the Vicomte de Souillac (who constructed the Chaussée in Port Louis[46] and encouraged farmers to settle in the district of Savanne) and Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux (who saw to it that the French in the Indian Ocean should have their headquarters in Mauritius instead of Pondicherry in India).[47] Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen was a successful general in the French Revolutionary Wars and, in some ways, a rival of Napoléon I. He ruled as Governor of Isle de France and Réunion from 1803 to 1810. British naval cartographer and explorer Matthew Flinders was arrested and detained by General Decaen on the island from 1803 to 1810,[48][49] in contravention of an order from Napoléon. During the Napoleonic Wars, Mauritius became a base from which French corsairs organised successful raids on British commercial ships. The raids continued until 1810, when a Royal Navy expedition led by Commodore Josias Rowley, R.N., an Anglo-Irish aristocrat, was sent to capture the island. Despite winning the Battle of Grand Port against the British, the French could not prevent the British from landing at Cap Malheureux three months later. They formally surrendered the island on the fifth day of the invasion, 3 December 1810,[47] on terms allowing settlers to keep their land and property and to use the French language and law of France in criminal and civil matters. Under British rule, the island's name reverted to Mauritius.[35]

British Mauritius (1810–1968) edit

The British administration, which began with Sir Robert Farquhar as its first governor, oversaw rapid social and economic changes. However, it was tainted by the Ratsitatane episode. Ratsitatane, nephew of King Radama of Madagascar, was brought to Mauritius as a political prisoner. He managed to escape from prison and plotted a rebellion that would free the island's slaves. He was betrayed by his associate Laizaf and was caught by a group of militiamen and summarily executed.[50][51]

In 1832, d'Épinay launched the first Mauritian newspaper (Le Cernéen), which was not controlled by the government. In the same year, there was a move by the procureur-general to abolish slavery without compensation to the slave owners. This gave rise to discontent, and, to check an eventual rebellion, the government ordered all the inhabitants to surrender their arms. Furthermore, a stone fortress, Fort Adelaide, was built on a hill (now known as the Citadel hill) in the centre of Port Louis to quell any uprising.[46] Slavery was gradually abolished over several years after 1833, and the planters ultimately received two million pounds sterling in compensation for the loss of their slaves, who had been imported from Africa and Madagascar during the French occupation.[52][53] The abolition of slavery had important effects on Mauritius's society, economy and population. The planters brought a large number of indentured labourers from India to work in the sugar cane fields. Between 1834 and 1921, around half a million indentured labourers were present on the island. They worked on sugar estates, factories, in transport and on construction sites. Additionally, the British brought 8,740 Indian soldiers to the island.[35] Aapravasi Ghat, in the bay at Port Louis and now a UNESCO site, was the first British colony to serve as a major reception centre for indentured servants. The labourers brought from India were not always fairly treated, and a German, Adolph von Plevitz, made himself the unofficial protector of these immigrants. In 1871 he helped them to write a petition that was sent to Governor Gordon. A commission was appointed and recommended several measures that would affect the lives of Indian labourers during the next fifty years.[47]

In 1885, a new constitution was introduced. It was referred to as Cens Démocratique and it incorporated some of the principles advocated by one of the Creole leaders, Onésipho Beaugeard. It created elected positions in the Legislative Council – although the franchise was restricted mainly to the white French and fair-skinned Indian elite who owned real estate. In 1886, Governor John Pope Hennessy nominated Gnanadicarayen Arlanda as the first ever Indo-Mauritian member of the ruling council – despite the sugar oligarchy's preference for rival Indo-Mauritian Emile Sandapa. Arlanda served until 1891.[54] In 1903, motorcars were introduced in Mauritius, and in 1910, the first taxis came into service. The electrification of Port Louis took place in 1909, and in the same decade the Mauritius Hydro Electric Company of the Atchia Brothers was authorised to provide power to the towns of upper Plaines Wilhems.

The 1910s were a period of political agitation. The rising middle class (made up of doctors, lawyers, and teachers) began to challenge the political power of the sugar cane landowners. Eugène Laurent, mayor of Port Louis, was the leader of this new group; his party, Action Libérale, demanded that more people should be allowed to vote in the elections. Action Libérale was opposed by the Parti de l'Ordre, led by Henri Leclézio, the most influential of the sugar magnates.[47] In 1911, there were riots in Port Louis due to a false rumour that Laurent had been murdered by the oligarchs in Curepipe. This became known as the 1911 Curepipe riots. Shops and offices were damaged in the capital, and one person was killed.[55] In the same year, 1911, the first public cinema shows took place in Curepipe, and, in the same town, a stone building was erected to house the Royal College.[55] In 1912, a wider telephone network came into service, used by the government, business firms, and a few private households.

World War I broke out in August 1914. Many Mauritians volunteered to fight in Europe against the Germans and in Mesopotamia against the Turks. But the war affected Mauritius much less than the wars of the eighteenth century. In fact, the 1914–1918 war was a period of great prosperity, due to a boom in sugar prices. In 1919, the Mauritius Sugar Syndicate came into being, which included 70% of all sugar producers.[56] The 1920s saw the rise of a "retrocessionism" movement, which favoured the retrocession of Mauritius to France. The movement rapidly collapsed because none of the candidates who wanted Mauritius to be given back to France were elected in the 1921 elections. In the post-war recession, there was a sharp drop in sugar prices. Many sugar estates closed down, marking the end of an era for the sugar magnates who had not only controlled the economy but also the political life of the country. From the end of nominated Arlanda's term in 1891, until 1926, there had been no Indo-Mauritian representation in the Legislative Council. However, at the 1926 elections, Dunputh Lallah and Rajcoomar Gujadhur became the first Indo-Mauritians to be elected to the Legislative Council. At Grand Port, Lallah won over rivals Fernand Louis Morel and Gaston Gebert; at Flacq, Gujadhur defeated Pierre Montocchio.[57] 1936 saw the birth of the Labour Party, launched by Maurice Curé. Emmanuel Anquetil rallied the urban workers while Pandit Sahadeo concentrated on the rural working class.[58] The Uba riots of 1937 resulted in reforms by the local British government that improved labour conditions and led to the un-banning of labour unions.[59][60] Labour Day was celebrated for the first time in 1938. More than 30,000 workers sacrificed a day's wage and came from all over the island to attend a giant meeting at the Champ de Mars.[61] Following the dockers' strikes, trade unionist Emmanuel Anquetil was deported to Rodrigues, Maurice Curé and Pandit Sahadeo were placed under house arrest, whilst numerous strikers were jailed. Governor Sir Bede Clifford assisted Mr Jules Leclezio of the Mauritius Sugar Syndicate to counter the effects of the strike by using alternative workers known as 'black legs'.[62] At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, many Mauritians volunteered to serve under the British flag in Africa and the Near East, fighting against the German and Italian armies. Mauritius was never really threatened, but in 1943, several British ships were sunk outside Port Louis by German submarines. In the initial stages of the war, locally recruited military formations were raised in order to defend the country in case the British imperial troops had to leave. On 24 March 1943, the Mauritius Regiment, was created as an imperial unit and a new subsidiary of the East Africa Command (EAC). In late 1943, the 1st Battalion of the Mauritius Regiment (1MR) was sent to Madagascar for training, and in their place a battalion of the King's African Rifles (KAR) was stationed in Mauritius. The dispatch of the 1MR proved to be politically unpopular on the basis of some troops resenting conscription and the battalion overseas comprising solely non-white troops, exacerbating racial tensions in the country. The 1MR troops were further aggrieved at the segregation they were subject to, unequal pay, physically demanding training, and were fearful of the Japanese soldiers, all these factors culminated in the 1MR mutinying.[63]

During World War II, conditions were hard in the country; the prices of commodities doubled but workers' salaries increased only by 10 to 20 percent. There was civil unrest, and the colonial government censored all trade union activities. However, the labourers of Belle Vue Harel Sugar Estate went on strike on 27 September 1943.[64] Police officers eventually fired directly at the crowd, resulting in the deaths of four labourers.[65] This became known as the 1943 Belle Vue Harel Massacre.[66][67] Social worker and leader of the Jan Andolan movement Basdeo Bissoondoyal organised the funeral ceremonies of the four dead labourers.[68] Three months later, on 12 December 1943, Bissoondoyal organised a mass gathering at "Marie Reine de la Paix" in Port Louis, and the significant crowd of workers from all over the island confirmed the popularity of the Jan Andolan movement.[69]

After the proclamation of the 1947 Constitution of Mauritius, the general elections were held on 9 August 1948 – and, for the first time, the colonial government expanded the franchise to all adults who could write their name in one of the island's 19 languages, abolishing the previous gender and property qualifications.[70][71] Guy Rozemont's Labour Party won the majority of the votes with 11 of the 19 elected seats won by Hindus. However, the Governor-General Donald Mackenzie-Kennedy appointed 12 Conservatives to the Legislative Council on 23 August 1948 to perpetuate the predominance of white Franco-Mauritians.[72][70] In 1948, Emilienne Rochecouste became the first woman to be elected to the Legislative Council.[73] Guy Rozemont's party bettered its position in 1953, and, on the strength of the election results, demanded universal suffrage. Constitutional conferences were held in London in 1955 and 1957, and the ministerial system was introduced. Voting took place for the first time on the basis of universal adult suffrage on 9 March 1959. The general election was again won by the Labour Party, led this time by Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam.[74]

A Constitutional Review Conference was held in London in 1961, and a programme of further constitutional advance was established. The 1963 election was won by the Labour Party and its allies. The Colonial Office noted that politics of a communal nature was gaining ground in Mauritius and that the choice of candidates (by parties) and the voting behaviour (of electors) were governed by ethnic and caste considerations.[74] Around that time, two eminent British academics, Richard Titmuss and James Meade, published a report of the island's social problems caused by overpopulation and the monoculture of sugar cane. This led to an intense campaign to halt the population explosion, and the decade registered a sharp decline in population growth.[citation needed]

In early 1965, a political assassination took place in the suburb of Belle-Rose, in the town of Quatre Bornes, where Labour activist Rampersad Surath was beaten to death by thugs of rival party Parti Mauricien.[75][76] On 10 May 1965, racial riots broke out in the village of Trois Boutiques near Souillac and progressed to the historic village of Mahébourg. A nationwide state of emergency was declared on the whole British colony. The riot was initiated by the murder of Police Constable Beesoo in his vehicle by a Creole gang. This was followed by the murder of a civilian named Mr. Robert Brousse in Trois Boutiques.[77] The Creole gang then proceeded to the coastal historic village of Mahébourg to assault the Indo-Mauritian spectators who were watching a Hindustani movie at Cinéma Odéon. Mahébourg police recorded nearly 100 complaints of assaults on Indo-Mauritians.[78]

Independence (since 1968) edit

At the Lancaster Conference of 1965, it became clear that Britain wanted to relieve itself of the colony of Mauritius. In 1959, Harold Macmillan had made his famous "Wind of Change Speech" in which he acknowledged that the best option for Britain was to give complete independence to its colonies. Thus, since the late fifties, the way was paved for independence.[79]

Later in 1965, after the Lancaster Conference, the Chagos Archipelago was excised from the territory of Mauritius to form the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). A general election took place on 7 August 1967, and the Independence Party obtained the majority of seats. In January 1968, six weeks before the declaration of independence the 1968 Mauritian riots occurred in Port Louis leading to the deaths of 25 people.[80][81]

Mauritius adopted a new constitution, and independence was proclaimed on 12 March 1968. Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam became the first prime minister of an independent Mauritius – with Queen Elizabeth II remaining head of state as Queen of Mauritius.

In 1969, the opposition party, Mauritian Militant Movement (MMM), was founded, led by Paul Bérenger. Later, in 1971, the MMM – backed by unions – called a series of strikes in the port, which caused a state of emergency in the country.[82]

The coalition government of the Labour Party and the PMSD (Parti Mauricien Social Démocrate) reacted by curtailing civil liberties and curbing freedom of the press.[55] Two unsuccessful apparent assassination attempts were made against Paul Bérenger in 1971, killing his supporter Fareed Muttur[83] and dock worker and activist Azor Adélaïde.[84] General elections were postponed and public meetings were prohibited. Members of the MMM, including Paul Bérenger, were imprisoned on 23 December 1971. The MMM leader was released a year later.[85]

In May 1975, a student revolt that started at the University of Mauritius swept across the country.[86] The students were unsatisfied with an education system that did not meet their aspirations, and that gave limited prospects for future employment. On 20 May, thousands of students tried to enter Port-Louis over the Grand River North West bridge, and clashed with police. An act of Parliament was passed on 16 December 1975 to extend the right to vote to 18-year-olds. This was seen as an attempt to appease the frustration of the younger generation.[51]

The next general elections took place on 20 December 1976. The Labour-CAM coalition won only 28 seats out of 62.[87] The MMM secured 34 seats in Parliament but outgoing Prime Minister Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam managed to remain in office, with a two-seat majority, after striking an alliance with the PMSD of Gaetan Duval.

In 1982 an MMM-PSM government (led by PM Anerood Jugnauth, Deputy PM Harish Boodhoo and Finance Minister Paul Bérenger) was elected. However, ideological and personality differences emerged within the MMM and PSM leadership. The power struggle between Bérenger and Jugnauth peaked in March 1983. Jugnauth travelled to New Delhi to attend a Non-Aligned Movement summit; on his return, Bérenger proposed constitutional changes that would strip power from the Prime Minister. At Jugnauth's request, PM Indira Gandhi of India planned an armed intervention involving the Indian Navy and Indian Army to prevent a coup under the code name Operation Lal Dora.[88][89][90]

The MMM-PSM government split up nine months after the June 1982 election. According to an Information Ministry official the nine months was a "socialist experiment".[91] Harish Boodhoo dissolved his party PSM to enable all PSM parliamentarians to join Jugnauth's new party MSM, thus remaining in power whilst distancing themselves from MMM.[92] The MSM-Labour-PMSD coalition was victorious at the August 1983 elections, resulting in Anerood Jugnauth as PM and Gaëtan Duval as Deputy PM.

That period saw growth in the EPZ (Export Processing Zone) sector. Industrialisation began to spread to villages as well, and attracted young workers from all ethnic communities. As a result, the sugar industry began to lose its hold on the economy. Large retail chains began opening stores in 1985 and offered credit facilities to low-income earners, thus allowing them to afford basic household appliances. There was also a boom in the tourism industry, and new hotels sprang up throughout the island. In 1989 the stock exchange opened its doors, and in 1992, the freeport began operation.[55] In 1990, the Prime Minister lost the vote on changing the Constitution to make the country a republic with Bérenger as president.[93]

Republic (since 1992) edit

On 12 March 1992, twenty-four years after independence, Mauritius was proclaimed a republic within the Commonwealth of Nations and the British monarch removed as head of state.[35] The last Governor-General of Mauritius, Sir Veerasamy Ringadoo, became the first President.[94] This was under a transitional arrangement, in which he was replaced by Cassam Uteem later that year.[95] Political power remained with the prime minister.

Despite an improvement in the economy, which coincided with a fall in the price of petrol and a favourable dollar exchange rate, the government did not enjoy full popularity. As early as 1984, there was discontent. Through the Newspapers and Periodicals Amendment Act, the government tried to make every newspaper provide a bank guarantee of half a million rupees. Forty-three journalists protested by participating in a public demonstration in Port Louis, in front of Parliament. They were arrested and freed on bail. This caused a public outcry and the government had to review its policy.[55]

There was also dissatisfaction in the education sector. There were not enough high-quality secondary colleges to answer the growing demand of primary school leavers who had got through their CPE (Certificate of Primary Education). In 1991, a master plan for education failed to get national support and contributed to the government's downfall.[55]

In December 1995, Navin Ramgoolam was elected as PM of the Labour–MMM alliance. In October 1996, the triple murder of political activists at Gorah-Issac Street in Port Louis led to several arrests and a long investigation.[96]

The year 1999 was marked by civil unrest and riots in February and then in May. Following the Kaya riots, President Cassam Uteem and Cardinal Jean Margéot toured the country and calm was restored after four days of turmoil.[97] A commission of enquiry was set up to investigate the root causes of the social disturbance. The resulting report delved into the cause of poverty and qualified many tenacious beliefs as perceptions.[98] In January 2000, political activist Rajen Sabapathee was shot dead after he escaped from La Bastille jail.[99]

Sir Anerood Jugnauth of the MSM returned to power in September 2000 after securing an alliance with the MMM. In 2002, the island of Rodrigues became an autonomous entity within the republic and was thus able to elect its own representatives to administer the island. In 2003, the prime ministership was transferred to Paul Bérenger of the MMM, and Sir Anerood Jugnauth became President. Bérenger was the first Franco-Mauritian Prime Minister in the country's post-Independence history.

In 2005 elections, Navin Ramgoolam became PM under the new coalition of Labour–PMXD–VF–MR–MMSM. In the 2010 elections the Labour–MSM–PMSD alliance secured power and Navin Ramgoolam remained PM until 2014.[100]

The MSM–PMSD–ML coalition was victorious at the 2014 elections under Anerood Jugnauth's leadership. Despite disagreements within the ruling alliance that led to the departure of PMSD, the MSM–ML stayed in power for their full 5-year term.[101]

On 21 January 2017, Sir Anerood Jugnauth announced his resignation and that his son and Finance Minister Pravind Jugnauth would assume the office of prime minister.[102] The transition took place as planned on 23 January 2017.[103]

In 2018, Mauritian president Ameenah Gurib-Fakim resigned over a financial scandal.[104] The incumbent president is Prithvirajsing Roopun[105] who has served since December 2019.

In the November 2019 Mauritius general elections, the ruling Militant Socialist Movement (MSM) won more than half of the seats in parliament, securing incumbent Prime Minister Pravind Kumar Jugnauth a new five-year term.[106]

On 25 July 2020, Japanese-owned bulk carrier MV Wakashio ran aground on a coral reef off the coast of Mauritius, leaking up to 1,000 tonnes of heavy oil into a pristine lagoon.[107] Its location on the edge of protected fragile marine ecosystems and a wetland of international importance made the MV Wakashio oil spill one of the worst environmental disasters ever to hit the western Indian Ocean.[108]

Geography edit

The total land area of the country is 2,040 km2 (790 sq mi). It is the 170th largest nation in the world by size. The Republic of Mauritius comprises Mauritius Island and several outlying islands. The nation's exclusive economic zone covers about 2.3 million km2 (890,000 sq mi) of the Indian Ocean, including approximately 400,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi) jointly managed with the Seychelles.[109][110][111]

Mauritius Island edit

Mauritius is 2,000 km (1,200 mi) off the southeast coast of Africa, between latitudes 19°58.8'S and 20°31.7'S and longitudes 57°18.0'E and 57°46.5'E. It is 65 km (40 mi) long and 45 km (30 mi) wide. Its land area is 1,864.8 km2 (720.0 sq mi).[112][113] The island is surrounded by more than 150 km (100 mi) of white sandy beaches, and the lagoons are protected from the open sea by the world's third-largest coral reef, which surrounds the island.[114] Just off the Mauritian coast lie some 49 uninhabited islands and islets, several of which have been declared natural reserves for endangered species.

Mauritius Island (Mauritian Creole: Lil Moris; French: Île Maurice, pronounced [il moʁis]) is relatively young geologically, having been created by volcanic activity some 8 million years ago. Together with Saint Brandon, Réunion, and Rodrigues, the island is part of the Mascarene Islands. These islands emerged as a result of gigantic underwater volcanic eruptions that happened thousands of kilometres to the east of the continental block made up of Africa and Madagascar.[115] They are no longer volcanically active and the hotspot now rests under Réunion Island. Mauritius is encircled by a broken ring of mountain ranges, varying in height from 300 to 800 metres (1,000 to 2,600 ft) above sea level. The land rises from coastal plains to a central plateau where it reaches a height of 670 m (2,200 ft); the highest peak is in the south-west, Piton de la Petite Rivière Noire at 828 metres (2,717 ft). Streams and rivers speckle the island, many formed in the cracks created by lava flows.

Rodrigues Island edit

The autonomous island of Rodrigues is located 560 km (350 mi) to the east of Mauritius, with an area 108 km2 (42 sq mi).[115] Rodrigues is a volcanic island rising from a ridge along the edge of the Mascarene Plateau. The island is hilly with a central spine culminating in the highest peak, Mountain Limon at 398 m (1,306 ft). The island also has a coral reef and extensive limestone deposits. According to Statistics Mauritius, at 1 July 2019, the population of the island was estimated at 43,371.[116]

Chagos Archipelago edit

The Chagos Archipelago is composed of atolls and islands, and is located approximately 2,200 kilometres north-east of the main island of Mauritius. Mauritius claims sovereignty over the archipelago, which forms the British Indian Ocean Territory and is de facto controlled by the United Kingdom.

To the north of the Chagos Archipelago are Peros Banhos, the Salomon Islands and Nelsons Island; to the south-west are The Three Brothers, Eagle Islands, Egmont Islands and Danger Island. Diego Garcia is in the south-east of the archipelago.[13] In 2016, the Chagossian population was estimated at 8,700 in Mauritius, including 483 natives; 350 Chagossians live in the Seychelles, including 75 natives, while 3,000, including 127 natives, live in the UK (the population having grown from the 1200 Chagossians who moved there).[117]

St. Brandon edit

St. Brandon, also known as Cargados Carajos Shoals, is located 402 kilometres (250 mi) northeast of Mauritius Island. Saint Brandon is an archipelago composed of the remnants of the lost micro continent of Mauritia[118] and consists of five island groups, with between 28 and 40 islands in total, depending on seasonal storms, cyclones, and related sand movements. In 2008, the Privy Council (United Kingdom) judgment (Article 71) confirmed Raphaël Fishing Company as the holder of a Permanent Grant of the thirteen islands mentioned in the 1901 Deed (transcribed in Vol TB25 No 342) subject to the conditions therein referred to;[119] In 2002, St. Brandon was classified in 10th place globally by UNESCO for inclusion as a World Heritage Site well ahead of any other Mauritian candidates at the time.[120]

Agaléga Islands edit

The twin islands of Agaléga are located some 1,000 kilometres (600 miles) to the north of Mauritius.[115] Its North Island is 12.5 km (7.8 mi) long and 1.5 km (0.93 mi) wide, while its South Island is 7 by 4.5 km (4.3 by 2.8 mi). The total area of both islands is 26 km2 (10 sq mi). According to Statistics Mauritius, at 1 July 2019, the population of Agaléga and St. Brandon was estimated at 274.[116]

Tromelin edit

Tromelin Island lies 430 km north-west of Mauritius. Mauritius claims sovereignty over Tromelin island, though it is registered as a part of France.

The French took control of Mauritius in 1715, renaming it Isle de France. France officially ceded Mauritius including all its dependencies to Britain through the Treaty of Paris, signed on 30 May 1814 and in which Réunion was returned to France. The British Colony of Mauritius consisted of the main island of Mauritius along with its dependencies Rodrigues, Agaléga, St. Brandon, Tromelin (disputed) and the Chagos Archipelago, while the Seychelles became a separate colony in 1906. It is disputed whether the transfer of Isle de France (as Mauritius was previously known under French rule) and its dependencies to Britain in 1814 included Tromelin island. Article 8 of the Treaty of Paris stipulate the cession by France to Britain of Isle de France "and its dependencies, namely Rodrigues and the Seychelles". France considers that the sovereignty of Tromelin island was never transferred to Britain. Mauritius's claim is based on the fact that the transfer of Isle de France and its dependencies to Britain in 1814 was general in nature, that it was beyond those called out in the Treaty of Paris, and that all the dependencies of Isle de France were not specifically mentioned in the Treaty. Mauritius's claim is that since Tromelin was a dependency of Isle de France, it was 'de facto' transferred to Britain in 1814. The islands of Agaléga, St Brandon and the Chagos Archipelago were also not specifically mentioned in the Treaty of Paris but became part of the British Colony of Mauritius as they were dependencies of Isle de France at that time. In addition, the British authorities in Mauritius had been taking administrative measures with respect to Tromelin over the years; for instance, British officials granted four guano operating concessions on Tromelin island between 1901 and 1951.[19] In 1959, British officials in Mauritius informed the World Meteorological Organization that it considered Tromelin to be part of its territory.[121] A co-management treaty was reached by France and Mauritius in 2010 but has not been ratified.[122]

Wildlife edit

Chagos Archipelago territorial dispute edit

Mauritius has long sought sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago, located 1,287 km (800 mi) to the north-east. Chagos was administratively part of Mauritius from the 18th century when the French first settled the islands. All of the islands forming part of the French colonial territory of Isle de France (as Mauritius was then known) were ceded to the British in 1810 under the Act of Capitulation signed between the two powers.[123] In 1965, three years before the independence of Mauritius, the United Kingdom split the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius and the islands of Aldabra, Farquhar and Desroches from the Seychelles to form the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). The islands were formally established as an overseas territory of the United Kingdom on 8 November 1965. On 23 June 1976, Aldabra, Farquhar and Desroches were returned to Seychelles as a result of its attaining independence. The BIOT now comprises the Chagos Archipelago only. The UK leased the main island of the archipelago, Diego Garcia, to the United States under a 50-year lease to establish a military base.[123][124] In 2016, Britain extended the lease to the US till 2036.[125] Mauritius has repeatedly asserted that the separation of its territories is a violation of United Nations resolutions banning the dismemberment of colonial territories before independence and claims that the Chagos Archipelago, including Diego Garcia, forms an integral part of the territory of Mauritius under both Mauritian law and international law.[126] Between 1968 and 1973, British officials forcibly expelled over 1,000 Chagossians to Mauritius and the Seychelles. As part of the deportation, British officials have been accused of ordering the island's dog population of 1,000 to be gassed.[127][128] At the United Nations and in statements to its Parliament, the UK stated that there was no "permanent population" in the Chagos Archipelago and described the population as "contract labourers" who were relocated.[12] Since 1971, only the atoll of Diego Garcia is inhabited, home to some 3,000 UK and US military and civilian contracted personnel. Chagossians have since engaged in activism to return to the archipelago, claiming that their forced expulsion and dispossession were illegal.[129][130]

Mauritius considers the territorial sea of the Chagos Archipelago and Tromelin island as part of its exclusive economic zone.[14]

On 20 December 2010, Mauritius initiated proceedings against the United Kingdom under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to challenge the legality of the Chagos Marine Protected Area (MPA), which the UK purported to declare around the Chagos Archipelago in April 2010. The dispute was arbitrated by the Permanent Court of Arbitration. The Tribunal's decision determined that the UK's undertaking to return the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius gives Mauritius an interest in significant decisions that bear upon possible future uses of the archipelago.[131]

On 25 February 2019, the judges of the International Court of Justice by thirteen votes to one stated that the United Kingdom is under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible. Only the American judge, Joan Donoghue, voted in favor of the UK. The president of the court, Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf, said the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago in 1965 from Mauritius had not been based on a "free and genuine expression of the people concerned". "This continued administration constitutes a wrongful act", he said, adding "The UK has an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible and that all member states must co-operate with the United Nations to complete the decolonization of Mauritius."[132]

On 22 May 2019, the United Nations General Assembly debated and adopted a resolution that affirmed that the Chagos Archipelago, which has been occupied by the UK for more than 50 years, "forms an integral part of the territory of Mauritius". The resolution gives effect to an advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), demanded that the UK "withdraw its colonial administration ... unconditionally within a period of no more than six months". 116 states voted in favour of the resolution, 55 abstained and only Australia, Hungary, Israel and Maldives supported the UK and US. During the debate, the Mauritian Prime Minister described the expulsion of Chagossians as "a crime against humanity".[133] While the resolution is not legally binding, it carries significant political weight since the ruling came from the UN's highest court and the assembly vote reflects world opinion.[134] The resolution also has immediate practical consequences: the UN, its specialised agencies, and all other international organisations are now bound, as a matter of UN law, to support the decolonisation of Mauritius even if the UK claim that it has no doubt about its sovereignty.[133]

Environment and climate edit

The environment in Mauritius is typically tropical in the coastal regions with forests in the mountainous areas. Seasonal cyclones are destructive to its flora and fauna, although they recover quickly. Mauritius ranked second in an air quality index released by the World Health Organization in 2011.[135] It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.46/10, ranking it 100th globally out of 172 countries.[136]

Situated near the Tropic of Capricorn, Mauritius has a tropical climate. There are 2 seasons: a warm humid summer from November to April, with a mean temperature of 24.7 °C (76.5 °F) and a relatively cool dry winter from June to September with a mean temperature of 20.4 °C (68.7 °F). The temperature difference between the seasons is only 4.3 °C (7.7 °F). The warmest months are January and February with average day maximum temperature reaching 29.2 °C (84.6 °F) and the coolest months are July and August with average overnight minimum temperatures of 16.4 °C (61.5 °F). Annual rainfall ranges from 900 mm (35 in) on the coast to 1,500 mm (59 in) on the central plateau. Although there is no marked rainy season, most of the rainfall occurs in the summer months. Sea temperature in the lagoon varies from 22–27 °C (72–81 °F). The central plateau is much cooler than the surrounding coastal areas and can experience as much as twice the rainfall. The prevailing trade winds keep the east side of the island cooler and bring more rain. Occasional tropical cyclones generally occur between January and March and tend to disrupt the weather for about three days, bringing heavy rain.[137]

Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth declared an environmental state of emergency after the 25 July 2020 MV Wakashio oil spill.[138] France sent aircraft and specialists from Réunion and Greenpeace said that the leak threatened the survival of thousands of species, who are at "risk of drowning in a sea of pollution".[139]

Biodiversity edit

The country is home to some of the world's rarest plants and animals, but human habitation and the introduction of non-native species have threatened its indigenous flora and fauna.[129] Due to its volcanic origin, age, isolation, and unique terrain, Mauritius is home to a diversity of flora and fauna not usually found in such a small area. Before the Portuguese arrival in 1507, there were no terrestrial mammals on the island. This allowed the evolution of a number of flightless birds and large reptile species. The arrival of humans saw the introduction of invasive alien species, the rapid destruction of habitat and the loss of much of the endemic flora and fauna. In particular, the extinction of the flightless dodo bird, a species unique to Mauritius, has become a representative example of human-driven extinction.[140][141][142] The dodo is prominently featured as a (heraldic) supporter of the national coat of arms of Mauritius.[143]

Less than 2% of the native forest now remains, concentrated in the Black River Gorges National Park in the south-west, the Bambous Mountain Range in the south-east, and the Moka-Port Louis Ranges in the north-west. There are some isolated mountains, Corps de Garde, Le Morne Brabant, and several offshore islands, with remnants of coastal and mainland diversity. Over 100 species of plants and animals have become extinct and many more are threatened. Conservation activities began in the 1980s with the implementation of programmes for the reproduction of threatened bird and plant species as well as habitat restoration in the national parks and nature reserves.[144]

In 2011, the Ministry of Environment & Sustainable Development issued the "Mauritius Environment Outlook Report," which recommended that St Brandon be declared a Marine protected area. In the President's Report of the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation dated March 2016, St Brandon is declared an official MWF project to promote the conservation of the atoll. [145]

The Mauritian flying fox is the only remaining mammal endemic to the island,and has been severely threatened in recent years due to the government sanctioned culling introduced in November 2015 due to the belief that they were a threat to fruit plantations. Prior to 2015 the lack of severe cyclone had seen the fruit bat population increase and the status of the species was then changed by the IUCN from Endangered to Vulnerable in 2014. October 2018, saw the authorisation of the cull of 20% of the fruit bat population, amounting to 13,000 of the estimated 65,000 fruit bats remaining, although their status had already reverted to Endangered due to the previous years' culls.[146]

Government and politics edit

The politics of Mauritius take place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic, in which the President is the head of state and the Prime Minister is the head of government, assisted by a Council of Ministers. Mauritius has a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the Government. Legislative power is vested in both the Government and the National Assembly.

The National Assembly is Mauritius's unicameral legislature, which was called the Legislative Assembly until 1992, when the country became a republic. It consists of 70 members, 62 elected for four-year terms in multi-member constituencies and eight additional members, known as "best losers", appointed by the Electoral Service Commission to ensure that ethnic and religious minorities are equitably represented. The UN Human Rights Committee (UNHRC), which monitors member states' compliance with the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights (ICPCR), has criticised the country's Best Loser System following a complaint by a local youth and trade union movement.[147] The president is elected for a five-year term by the Parliament.

The island of Mauritius is divided into 20 constituencies that return three members each. The island of Rodrigues is a single district that returns two members.

After a general election, the Electoral Supervisory Commission may nominate up to eight additional members with a view to correct any imbalance in the representation of ethnic minorities in Parliament. This system of nominating members is commonly called the best loser system.

The political party or party alliance that wins the majority of seats in Parliament forms the government. Its leader becomes the Prime Minister, who selects the Cabinet from elected members of the Assembly, except for the Attorney General of Mauritius, who may not be an elected member of the Assembly. The political party or alliance which has the second largest group of representatives forms the Official Opposition and its leader is normally nominated by the President of the Republic as the Leader of the Opposition. The Assembly elects a Speaker, a Deputy Speaker and a Deputy Chairman of Committees as some of its first tasks.

Mauritius is a democracy with a government elected every five years. The most recent National Assembly Election was held on 7 November 2019 in all the 20 mainland constituencies, and in the constituency covering the island of Rodrigues. Elections have tended to be a contest between two major coalitions of parties.

The 2018 Ibrahim Index of African Governance ranked Mauritius first in good governance.[148] According to the 2017 Democracy Index compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit that measures the state of democracy in 167 countries, Mauritius ranks 16th worldwide and is the only African-related country with "full democracy".[149]

| Office held | Office holder | Incumbency[150] |

|---|---|---|

| President | Prithvirajsing Roopun | 2 December 2019[151] |

| Prime Minister | Pravind Jugnauth | 23 January 2017 |

| Vice President | Marie Cyril Eddy Boissézon | 2 December 2019[151] |

| Deputy Prime Minister | Steven Obeegadoo | 25 June 2020 |

| Chief Justice | Rehana Mungly-Gulbul | 18 November 2021 |

| Speaker of the National Assembly | Sooroojdev Phokeer | 21 November 2019 |

| Leader of the Opposition | Xavier-Luc Duval | 4 March 2021 |

Administrative subdivisions edit

Mauritius has a single first-order administrative division, the Outer Islands of Mauritius (French: Îles éparses de Maurice), which consists of the islands of Mauritius and several outlying islands.[152]

Mauritius comprises the island of Mauritius and Outer Islands of Mauritius. The following are the island-groups in Mauritius:

- Island of Mauritius

- Rodrigues

- Saint Brandon (Cargados Carajos)

- Agaléga

The island of Mauritius is subdivided into nine districts, which are the country's second-order administrative divisions.

Military edit

All military, police, and security functions in Mauritius are carried out by 10,000 active-duty personnel under the Commissioner of Police. The 8,000-member National Police Force is responsible for domestic law enforcement. The 1,400-member Special Mobile Force (SMF) and the 688-member National Coast Guard are the only two paramilitary units in Mauritius. Both units are composed of police officers on lengthy rotations to those services. Mauritius has also a special operations military known as 'GIPM' that would intervene in any terrorist attack or high risk operations.[153]

Foreign relations edit

Mauritius has strong and friendly relations with various African, American, Asian, European and Oceanic countries. Considered part of Africa geographically, Mauritius has friendly relations with African states in the region, particularly South Africa, by far its largest continental trading partner. Mauritian investors are gradually entering African markets, notably Madagascar, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. The country's political heritage and dependence on Western markets have led to close ties with the European Union and its member states, particularly France. Relations with India are very strong for both historical and commercial reasons. Mauritius established diplomatic relations with China in April 1972 and was forced to defend this decision, along with naval contracts with the USSR in the same year. It has also been extending its Middle East outreach with the setting up of an embassy in Saudi Arabia[154] whose Ambassador also doubles as the country's ambassador to Bahrain.[155]

Mauritius is a member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the African Union, the Commonwealth of Nations, La Francophonie, the Southern Africa Development Community, the Indian Ocean Commission, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, and the Indian Ocean Rim Association.

Legal system edit

Mauritius has a hybrid legal system derived from English common law and the French civil law. The Constitution of Mauritius established the separation of powers between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary and guaranteed the protection of the fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual. Mauritius has a single-structured judicial system consisting of two tiers, the Supreme Court and subordinate courts. The Supreme Court is composed of various divisions exercising jurisdiction such as the Master's Court, the Family Division, the Commercial Division (Bankruptcy), the Criminal Division, the Mediation Division, the Court of First Instance in civil and criminal proceedings, the Appellate jurisdiction: the Court of Civil Appeal and the Court of Criminal Appeal. Subordinate courts consist of the Intermediate Court, the Industrial Court, the District Courts, the Bail and Remand Court and the Court of Rodrigues. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council is the final court of appeal of Mauritius. After the independence of Mauritius in 1968, Mauritius maintained the Privy Council as its highest court of appeal. Appeals to the Judicial Committee from decisions of the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court may be as of right or with the leave of the Court, as set out in section 81 of the Constitution and section 70A of the Courts Act. The Judicial Committee may also grant special leave to appeal from the decision of any court in any civil or criminal matter as per section 81(5) of the Constitution.[156]

There are no legal restrictions against homosexuality in Mauritius.[157][158]

Demographics edit

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port Louis Vacoas-Phoenix |

1 | Port Louis | Port Louis | 155,226 | Beau Bassin-Rose Hill Curepipe | ||||

| 2 | Vacoas-Phoenix | Plaines Wilhems | 115,289 | ||||||

| 3 | Beau Bassin-Rose Hill | Plaines Wilhems | 111,355 | ||||||

| 4 | Curepipe | Plaines Wilhems | 78,618 | ||||||

| 5 | Quatre Bornes | Plaines Wilhems | 77,308 | ||||||

| 6 | Triolet | Pamplemousses | 23,269 | ||||||

| 7 | Goodlands | Rivière du Rempart | 20,910 | ||||||

| 8 | Centre de Flacq | Flacq | 17,710 | ||||||

| 9 | Bel Air Rivière Sèche | Flacq | 17,671 | ||||||

| 10 | Mahébourg | Grand Port | 17,042 | ||||||

Mauritius had a population of 1,235,260 (608,090 males, 627,170 females) according to the final results of the 2022 Census. The population on the island of Mauritius was 1,191,280 (586,590 males and 604,690 females), and that of Rodrigues island was 43,650 (21,330 males and 22,320 females); Agalega island total population of 330 (170 males and 160 females).[7][8][3] Mauritius has the second highest population density in Africa. According to the 2022 census, the average age of the population was 38 years.[7][8][3] 2022 Census indicated that: The proportion of children aged below 15 years went down from 20.7% in 2011 to 15.4% in 2022; The share of persons aged 60 years and over has risen from 12.7% in 2011 to 18.7% in 2022.[3] Subsequent to a Constitutional amendment in 1982, the census does not compile data on ethnic identities anymore but still does on religious affiliation. The 1972 census was the last one to measure ethnicity.[160][161] Mauritius is a multiethnic society, drawn from Indian, African, Chinese and European (mostly French) origin.

According to the Constitution of Mauritius, there are 4 distinct communities on the island for the purposes of representation in the National Assembly. Schedule I, Paragraph 3(4) of the Constitution states that The population of Mauritius shall be regarded as including a Hindu community, a Muslim community, and a Sino-Mauritian community, and every person who does not appear, from his way of life, to belong to one or other of those three communities shall be regarded as belonging to the General Population, which shall itself be regarded as a fourth community.[162] Thus each ethnic group in Mauritius falls within one of the four main communities known as Hindus, General Population, Muslims and Sino-Mauritians.[163][164]

As per the above constitutional provision, the 1972 ethnic statistics are used to implement the Best Loser System, the method used in Mauritius since the 1950s to guarantee ethnic representation across the entire electorate in the National Assembly without organising the representation wholly by ethnicity.[165]

Religion edit

According to the 2011 census conducted by Statistics Mauritius, 48.5% of the Mauritian population follows Hinduism, followed by Christianity (32.7%), out of which 26.3% are Catholic, Islam (17.2%) and other religions (0.7%). 0.7% reported themselves as non-religious and 0.1% did not answer.[5] The constitution prohibits discrimination on religious grounds and provides for freedom to practice, change one's religion or not have any. The Roman Catholic Church, Church of England, Presbyterian Church of Mauritius, Seventh-day Adventists, Hindu Temples Associations and Muslim Mosques Organisations enjoy tax-exemptions and are allocated financial support based on their respective share of the population. Other religious groups can register and be tax-exempt but receive no financial support.[166] Public holidays of religious origins are the Hindu festivals of Maha Shivaratri, Ougadi, Thaipoosam Cavadee, Ganesh Chaturthi, and Diwali; the Christian festivals of All Saints Day and Christmas; and the Muslim festival of Eid al-Fitr.[167] The state actively participates in their organisation with special committees presiding over the pilgrimage to Ganga Talao for Maha Shivaratri and the annual Catholic Procession to Jacques-Désiré Laval's resting place at Sainte-Croix.[168]

Languages edit

The Mauritian constitution makes no mention of an official language. The Constitution only mentions that the official language of the National Assembly is English; however, any member can also address the chair in French.[169] English and French are generally considered to be de facto national and common languages of Mauritius, as they are the languages of government administration, courts, and business.[170] The constitution of Mauritius is written in English, while some laws, such as the Civil and Criminal codes, are in French. The Mauritian currency features the Latin, Tamil and Devanagari scripts.

The Mauritian population is multilingual; while Mauritian Creole is the mother tongue of most Mauritians, most people are also fluent in English and French; they tend to switch languages according to the situation.[171] French and English are favoured in educational and professional settings, while Asian languages are used mainly in music, religious and cultural activities. The media and literature are primarily in French.

The Mauritian Creole language, which is French-based with some additional influences, is spoken by the majority of the population as a native language.[172] The Creole languages which are spoken in different islands of the country are more or less similar: Mauritian Creole, Rodriguan creole, Agalega creole and Chagossian creole are spoken by people from the islands of Mauritius, Rodrigues, Agaléga and Chagos. The following ancestral languages, also spoken in Mauritius, have received official recognition by acts of parliament:[173] Bhojpuri,[174] Chinese,[175] Hindi,[176] Marathi,[177] Sanskrit,[178] Tamil,[179] Telugu[180] and Urdu.[181] Bhojpuri, once widely spoken as a mother tongue, has become less commonly spoken over the years. According to the 2022 census, Bhojpuri was spoken by 5.1% of the population compared to 12.1% in 2000.[3][182]

School students must learn English and French; they may also opt for an Asian language or Mauritian Creole. The medium of instruction varies from school to school but is usually English for public and government subsidised private schools and mainly French for paid private ones. O-Level and A-Level Exams are organised in public and government subsidised private schools in English by Cambridge International Examinations while paid private schools mostly follow the French Baccalaureate model.

Education edit

The education system in Mauritius consists of pre-primary, primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. The education structure consists of two to three years of pre-primary school, six years of primary schooling leading to the Primary School Achievement Certificate, five years of secondary education leading to the School Certificate, and two years of higher secondary ending with the Higher School Certificate. Secondary schools have "college" as part of their title. The government of Mauritius provides free education to its citizens from pre-primary to tertiary level. In 2013 government expenditure on education was estimated at ₨ 13,584 million, representing 13% of total expenditure.[183] As of January 2017, the government has introduced changes to the education system with the Nine-Year Continuous Basic Education programme, which abolished the Certificate of Primary Education (CPE).[184]

The O-Level and A-Level examinations are carried out by the University of Cambridge through University of Cambridge International Examinations in collaboration with the MES. The tertiary education sector includes universities and other technical institutions in Mauritius. The two main public universities are the University of Mauritius and the University of Technology, in addition to the Université des Mascareignes, founded in 2012, and the Open University Mauritius. These four public universities and several other technical institutes and higher education colleges are tuition-free for students as of 2019.[185]

The adult literacy rate was at 91.9% in 2022 with 8.8% of the total population holding a tertiary level qualification.[7][8][3] Mauritius was ranked 57th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, 1st in Africa.[186][187]

Economy edit

Mauritius is often described as Africa's most developed country.[188][189]Since independence from Britain in 1968, Mauritius has developed from a low-income, agriculture-based economy to a high-income diversified economy, based on tourism, textiles, sugar, and financial services. The economic history of Mauritius since independence has been called "the Mauritian Miracle" and the "success of Africa" (Romer, 1992; Frankel, 2010; Stiglitz, 2011).[190]

In recent years, information and communication technology, seafood, hospitality and property development, healthcare, renewable energy, and education and training have emerged as important sectors, attracting substantial investment from both local and foreign investors.[4]

Mauritius has no exploitable fossil fuel reserves and so relies on petroleum products to meet most of its energy requirements. Local and renewable energy sources are biomass, hydro, solar and wind energy.[191]

Mauritius has one of the largest exclusive economic zones in the world, and in 2012 the government announced its intention to develop the marine economy.[192]

Mauritius is ranked high in terms of economic competitiveness, a friendly investment climate, good governance and a free economy.[193][194][195] The Gross Domestic Product (PPP) was estimated at US$29.187 billion in 2018, and GDP (PPP) per capita was over US$22,909, the second highest in Africa.[193][194][195]

Mauritius has a high-income economy, according to the World Bank in 2019.[27] The World Bank's 2019 Ease of Doing Business Index ranks Mauritius 13th worldwide out of 190 economies in terms of ease of doing business. According to the Mauritian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the country's challenges are heavy reliance on a few industry sectors, high brain drain, scarcity of skilled labour, ageing population and inefficient public companies and para-statal bodies.[196]

Mauritius has built its success on a free market economy. According to the 2019 Economic Freedom of the World report, Mauritius is ranked as having the 9th most free economy in the world.[197]

Financial services edit

According to the Financial Services Commission, financial and insurance activities contributed to 11.1% of the country's GDP in 2018.[198] Over the years, Mauritius has been positioning itself as the preferred hub for investment into Africa due its strategic location between Asia and Africa, hybrid regulatory framework, ease of doing business, investment protection treaties, non-double taxation treaties, highly qualified and multilingual workforce, political stability, low crime rate coupled with modern infrastructure and connectivity. It is home to a number of international banks, legal firms, corporate services, investment funds and private equity funds. Financial products and services include private banking, global business, insurance and reinsurance, limited companies, protected cell companies, trust and foundation, investment banking, global headquarter administration.[199][200]

Corporate tax rate ranges from 15% to 17% and individual tax rate ranges from 10% to 25%.[201][202] While the country also offer incentives such as tax holidays and exemptions in some specific sectors to boost its competitiveness, the country is often tagged as a tax haven by the press due to individuals and companies who engaged in abusive practices in its financial sector.[203] The country has built up a solid reputation by making use of best practices and adopting a strong legal and regulatory framework to demonstrate its compliance with international demands for greater transparency.[204] In June 2015, Mauritius adhered to the multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters, and has an exchange information mechanism with 127 jurisdictions. Mauritius is a founding member of the Eastern and Southern Africa Anti Money Laundering Group and has been at the forefront in the fight against money laundering and other forms of financial crime. The country has adopted exchange of information on an automatic basis under the Common Reporting Standard and the Foreign Accounts Tax Compliance Act.[205]

Tourism edit

Mauritius is a major tourist destination, and the tourism sector is one of the main pillars of the Mauritian economy. The island nation enjoys a tropical climate with clear warm sea waters, beaches, tropical fauna and flora, complemented by a multi-ethnic and cultural population.[206] The forecast of tourist arrivals for the year 2019 is maintained at 1,450,000, representing an increase of 3.6% over the figure of 1,399,408 in 2018.[207]

Mauritius currently has two UNESCO World Heritage Sites, namely, Aapravasi Ghat and Le Morne Cultural Landscape. Additionally, Black River Gorges National Park is currently in the UNESCO tentative list.[208]

Transport edit

Since 2005 public buses, and later trains, in Mauritius have been free of charge for students, people with disabilities, and senior citizens.[209] The Metro Express railway currently links all five cities and the University of Mauritius at Réduit with planned expansion to the east and south. Former privately owned industrial railways have been abandoned since the 1960s. The harbour of Port Louis handles international trade as well as a cruise terminal. The Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam International Airport, the largest one in the Indian Ocean, is the main international airport and serves as the home operating base for the national airline Air Mauritius.[210] The Plaine Corail Airport operates from Rodrigues ensuring air link with the main island of Mauritius and international flights with Réunion.

Information and communications technology (ICT) edit

The information and communications technology (ICT) sector has contributed to 5.7% of its GDP in 2016.[211]

Additionally, the African Network Information Centre (AFRINIC) – the regional Internet registry for Africa – is headquartered in Ebene.

Mauritius is also connected to global Internet infrastructure via multiple optical fibre submarine communications cables, including the Lower Indian Ocean Network (LION) cable, the Mauritius–Rodrigues Submarine Cable, and the South Africa Far East (SAFE) cable.

Culture edit

Art edit

Prominent Mauritian painters include Henri Le Sidaner, Malcolm de Chazal, Raouf Oderuth and Vaco Baissac while Gabrielle Wiehe is a prominent illustrator and graphic designer.[212]

The Mauritius "Post Office" stamps, the first stamps produced outside Great Britain, among the rarest postage stamps in the world, are widely considered "the greatest item in all philately".[213]

Architecture edit

The distinctive architecture of Mauritius reflects the island nation's history as a colonial trade base connecting Europe with the East. Styles and forms introduced by Dutch, French, and British settlers from the seventeenth century onward, mixed with influences from India and East Africa, resulted in a unique hybrid architecture of international historic, social, and artistic significance. Mauritian structures present a variety of designs, materials, and decorative elements that are unique to the country and inform the historical context of the Indian Ocean and European colonialism.[214]

Decades of political, social, and economic change have resulted in the routine destruction of Mauritian architectural heritage. Between 1960 and 1980, the historic homes of the island's high grounds, known locally as campagnes, disappeared at alarming rates. More recent years have witnessed the demolition of plantations, residences, and civic buildings as they have been cleared or drastically renovated for new developments to serve an expanding tourism industry. The capital city of Port Louis remained relatively unchanged until the mid-1990s, yet now reflects the irreversible damage that has been inflicted on its built heritage. Rising land values are pitted against the cultural value of historical structures in Mauritius, while the prohibitive costs of maintenance and the steady decline in traditional building skills make it harder to invest in preservation.[214]

The general populace historically lived in what are termed creole houses.[215]

Literature edit

Mauritius is remembered in literature mostly for the novel Paul et Virginie, a classic of French literature, by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre and for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland's Dodo

Jean-Marie Le Clézio, Ananda Devi, Nathacha Appanah, Malcolm de Chazal, Eugénie Poujade, Marie-Thérèse Humbert, Shenaz Patel, Khal Torabully, Aqiil Gopee, South-African born Lindsey Collen-Seegobin writing in English and French, Dev Virahsawmy writing mostly in Mauritian Creole and Abhimanyu Unnuth writing in Hindi are some of the most prominent Mauritian writers. Le Clézio, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2008, is of Mauritian heritage and holds dual French-Mauritian citizenship. The island plays host to the Le Prince Maurice Prize. In keeping with the island's literary culture the prize alternates on a yearly basis between English-speaking and French-speaking writers.

Media edit

Music edit

The major musical genres of Mauritius are Sega and its fusion genre, Seggae, Bhojpuri folk songs, Indian movie music especially Bollywood, and Classical music mainly Western classical music and Indian classical music.

Cuisine edit

Mauritian cuisine is a combination of Indian, Creole, French and Chinese, with many dishes unique to the island. Spices are also a major component of Mauritian cuisine. There is a local variant of Persian falooda, locally known as alouda, which is a cold beverage made with milk, basil seeds, and agar-agar jelly. Locally made French pastry and bread are sold in most localities. Popular hawker meals include a wrap called dholl puri, rice-based biryani and gâteau piment.[216]

-

Fish fritters

-

Chop suey shrimp

-

Fish curry

Holidays and festivals edit

The public holidays of Mauritius involve the blending of several cultures from Mauritius's history. There are Hindu festivals, Christian festivals, Chinese festivals, and Muslim festivals.[217] There are 14 annual public holidays in Mauritius with New Year celebrated over two days if it falls on a weekend. All the public holidays related to religious festivals have dates that vary from year to year except for Christmas. Other festivals such as Holi, Raksha Bandhan, Durga Puja,[218] Père Laval Pilgrimage also enrich the cultural landscape of Mauritius.

| Public holidays in Mauritius in 2023[219] | Date |

|---|---|

| New Year's Day | Sunday 1 January – Monday 2 January |

| Chinese Spring Festival | Sunday 22 January |

| Abolition of slavery | Wednesday 1 February |

| Thaipoosam Cavadee | Saturday 4 February |

| Maha Shivaratri | Saturday 18 February |

| Independence and Republic Day | Sunday 12 March |

| Ugadi | Wednesday 22 March |

| Eid ul-Fitr (Depending on the visibility of the moon) | Saturday 22 April |

| Labour Day | Monday 1 May |

| Ganesh Chaturthi | Wednesday 20 September |

| All Saints Day | Wednesday 1 November |

| Arrival of the Indentured Labourers | Thursday 2 November |

| Diwali | Sunday 12 November |

| Christmas Day | Monday 25 December |

Sports edit

The most popular sport in Mauritius is football[220] and the national team is known as The Dodos or Club M. Other popular sports in Mauritius include cycling, table tennis, horse racing, badminton, volleyball, basketball, handball, boxing, judo, karate, taekwondo, weightlifting, bodybuilding and athletics. Water sports include swimming, sailing, scuba diving, windsurfing and kitesurfing.

Horseracing, which dates from 1812 when the Champ de Mars Racecourse was inaugurated, remains popular. The country hosted the second (1985), fifth (2003) and tenth editions (2019) of the Indian Ocean Island Games. Mauritius won its first Olympic medal at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing when boxer Bruno Julie won the bronze medal.

In golf, the former Mauritius Open and the current AfrAsia Bank Mauritius Open have been part of the European Tour.

See also edit

- Official Mauritius

- Mauritian Creole

- Demographics of Mauritius

- History of Mauritius