Summary

| Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

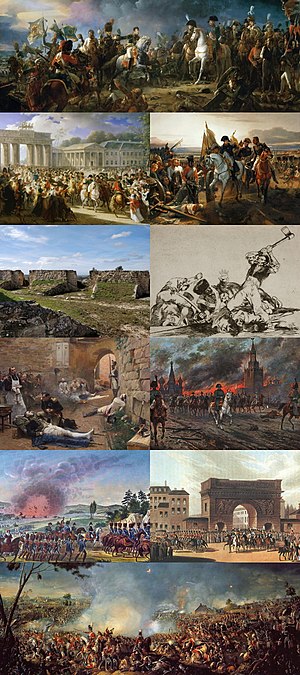

Click an image to load the campaign. Left to right, top to bottom: Battles of Austerlitz, Berlin, Friedland, Lisbon, Madrid, Vienna, Moscow, Leipzig, Paris, Waterloo | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

France and its client states: French clients: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

Other coalition members: 100,000 regulars and militia at peak strength (1813) Total: 3,000,000 regulars and militia at peak strength (1813) |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of conflicts fought between the First French Empire under Napoleon (1804–1815) and a fluctuating array of European coalitions. The wars originated in political forces arising from the French Revolution (1789–1799) and from the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802), and produced a period of French domination over Continental Europe.[32] The wars are categorised as seven conflicts, five named after the coalitions that fought Napoleon, plus two named for their respective theatres; the War of the Third Coalition, War of the Fourth Coalition, War of the Fifth Coalition, War of the Sixth Coalition, War of the Seventh Coalition, the Peninsular War, and the French invasion of Russia.[33]

The first stage of the war broke out with Britain having declared war on France on 18 May 1803, alongside the Third Coalition. In December 1805, Napoleon defeated the allied Russo-Austrian army at Austerlitz, thus forcing Austria to make peace. Concerned about increasing French power, Prussia led the creation of the Fourth Coalition, which resumed war in October 1806. Napoleon soon defeated the Prussians at Jena-Auerstedt and the Russians at Friedland, bringing an uneasy peace to the continent. The treaty had failed to end the tension, and war broke out again in 1809, with the Austrian-led Fifth Coalition. At first, the Austrians won a significant victory at Aspern-Essling, but were quickly defeated at Wagram.

Hoping to isolate and weaken Britain economically through his Continental System, Napoleon launched an invasion of Portugal, the only remaining British ally in continental Europe. After occupying Lisbon in November 1807, and with the bulk of French troops present in Spain, Napoleon seized the opportunity to turn against his former ally, depose the reigning Spanish royal family and declare his brother King of Spain in 1808 as José I. The Spanish and Portuguese thus revolted, with British support, and expelled the French from Iberia in 1814 after six years of fighting.

Concurrently, Russia, unwilling to bear the economic consequences of reduced trade, routinely violated the Continental System, prompting Napoleon to launch a massive invasion of Russia in 1812. The resulting campaign ended in disaster for France and the near-destruction of Napoleon's Grande Armée.

Encouraged by the defeat, Austria, Prussia, Sweden, and Russia formed the Sixth Coalition and began a new campaign against France, decisively defeating Napoleon at Leipzig in October 1813. The Allies then invaded France from the east, while the Peninsular War spilled over into southwestern France. Coalition troops captured Paris at the end of March 1814, forced Napoleon to abdicate in April, exiled him to the island of Elba, and restored power to the Bourbons. Napoleon escaped in February 1815, and reassumed control of France for around one Hundred Days. The allies formed the Seventh Coalition, which defeated him at Waterloo in June 1815, and exiled him to the island of Saint Helena, where he died six years later.[34]

The wars had profound consequences on global history, including the spread of nationalism and liberalism, advancements in civil law, the rise of Britain as the world's foremost naval and economic power, the appearance of independence movements in Spanish America and the subsequent decline of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires, the fundamental reorganization of German and Italian territories into larger states, and the introduction of radically new methods of conducting warfare. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Congress of Vienna redrew Europe's borders and brought a relative peace to the continent, lasting until the Crimean War in 1853.

Overview edit

Napoleon seized power in 1799, establishing a military dictatorship.[35] There are numerous opinions on the date to use as the formal beginning of the Napoleonic Wars; 18 May 1803 is often used, when Britain and France ended the only short period of peace between 1792 and 1814.[36] The Napoleonic Wars began with the War of the Third Coalition, which was the first of the Coalition Wars against the First French Republic after Napoleon's accession as leader of France.

Britain ended the Treaty of Amiens, declaring war on France in May 1803. Among the reasons were Napoleon's changes to the international system in Western Europe, especially in Switzerland, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. Historian Frederick Kagan argues that Britain was irritated in particular by Napoleon's assertion of control over Switzerland. Furthermore, Britons felt insulted when Napoleon stated that their country deserved no voice in European affairs, even though King George III was an elector of the Holy Roman Empire. For its part, Russia decided that the intervention in Switzerland indicated that Napoleon was not looking toward a peaceful resolution of his differences with the other European powers.[36]

The British hastily enforced a naval blockade of France to starve it of resources. Napoleon responded with economic embargoes against Britain, and sought to eliminate Britain's Continental allies to break the coalitions arrayed against him. The so-called Continental System formed a League of Armed Neutrality to disrupt the blockade and enforce free trade with France. The British responded by capturing the Danish fleet, breaking up the league, and later secured dominance over the seas, allowing it to freely continue its strategy.

Napoleon won the War of the Third Coalition at Austerlitz, forcing the Austrian Empire out of the war, and formally dissolving the Holy Roman Empire. Within months, Prussia declared war, triggering a War of the Fourth Coalition. This war ended disastrously for Prussia, which had been defeated and occupied within 19 days of the beginning of the campaign. Napoleon subsequently defeated Russia at Friedland, creating powerful client states in Eastern Europe and ending the Fourth Coalition.

Concurrently, the refusal of Portugal to commit to the Continental System, and Spain's failure to maintain it, led to the Peninsular War and the outbreak of the War of the Fifth Coalition. The French occupied Spain and formed a Spanish client kingdom, ending the alliance between the two. Heavy British involvement in the Iberian Peninsula soon followed, while a British effort to capture Antwerp failed. Napoleon oversaw the situation in Iberia, defeating the Spanish, and expelling the British from the Peninsula. Austria, eager to recover territory lost during the War of the Third Coalition, invaded France's client states in Eastern Europe in April 1809. Napoleon defeated the Fifth Coalition at Wagram.

Plans to invade British North America pushed the United States to declare war on Britain in the War of 1812, but it did not become an ally of France. Grievances over control of Poland, and Russia's withdrawal from the Continental System, led to Napoleon invading Russia in June 1812. The invasion was an unmitigated disaster for Napoleon; scorched earth tactics, desertion, French strategic failures and the onset of the Russian winter compelled Napoleon to retreat with massive losses. Napoleon suffered further setbacks: French power in the Iberian Peninsula was broken at the Battle of Vitoria the following summer, and a new alliance began, the War of the Sixth Coalition.

The coalition defeated Napoleon at Leipzig, precipitating his fall from power and eventual abdication on 6 April 1814. The victors exiled Napoleon to Elba and restored the Bourbon monarchy. Napoleon escaped from Elba in 1815, gathering enough support to overthrow the monarchy of Louis XVIII, triggering a seventh, and final, coalition against him. Napoleon was then decisively defeated at Waterloo, and he abdicated again on 22 June. On 15 July, he surrendered to the British at Rochefort, and was permanently exiled to remote Saint Helena. The Treaty of Paris, signed on 20 November 1815, formally ended the war.

The Bourbon monarchy was once again restored, and the victors began the Congress of Vienna to restore peace to Europe. As a direct result of the war, the Kingdom of Prussia rose to become a great power,[37] while Great Britain, with its unequalled Royal Navy and growing Empire, became the world's dominant superpower, beginning the Pax Britannica.[38] The Holy Roman Empire had been dissolved, and the philosophy of nationalism that emerged early in the war contributed greatly to the later unification of the German states, and those of the Italian peninsula. The war in Iberia greatly weakened Spanish power, and the Spanish Empire began to unravel; Spain would lose nearly all of its American possessions by 1833. The Portuguese Empire also shrank, with Brazil declaring independence in 1822.[39]

The wars revolutionised European warfare; the application of mass conscription and total war led to campaigns of unprecedented scale, as whole nations committed all their economic and industrial resources to a collective war effort.[40] Tactically, the French Army had redefined the role of artillery, while Napoleon emphasised mobility to offset numerical disadvantages,[41] and aerial surveillance was used for the first time in warfare.[42] The highly successful Spanish guerrillas demonstrated the capability of a people driven by fervent nationalism against an occupying force.[43][page range too broad] Due to the longevity of the wars, the extent of Napoleon's conquests, and the popularity of the ideals of the French Revolution, the period had a deep impact on European social culture. Many subsequent revolutions, such as that of Russia, looked to the French as a source of inspiration,[44] while its core founding tenets greatly expanded the arena of human rights and shaped modern political philosophies in use today.[45]

Background edit

The outbreak of the French Revolution had been received with great alarm by the rulers of Europe's continental powers, further exacerbated by the execution of Louis XVI, and the overthrow of the French monarchy. In 1793, Austria, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Kingdom of Naples, Prussia, the Kingdom of Spain, and the Kingdom of Great Britain formed the First Coalition to curtail the growing power of revolutionary France. Measures such as mass conscription, military reforms, and total war allowed France to defeat the coalition, despite the concurrent civil war in France. Napoleon, then a general of the French Revolutionary Army, forced the Austrians to sign the Treaty of Campo Formio, leaving only Great Britain opposed to the fledgling French Republic.

A Second Coalition was formed in 1798 by Great Britain, Austria, Naples, the Ottoman Empire, the Papal States, Portugal, Russia, and Sweden. The French Republic, under the Directory, suffered from heavy levels of corruption and internal strife. The new republic also lacked funds, no longer enjoying the services of Lazare Carnot, the minister of war who had guided France to its victories during the early stages of the Revolution. Bonaparte, commander of the Armée d'Italie in the latter stages of the First Coalition, had launched a campaign in Egypt, intending to disrupt the British control of India. Pressed from all sides, the Republic suffered a string of successive defeats against revitalised enemies, who were supported by Britain's financial help.

Bonaparte returned to France from Egypt on 23 August 1799, his campaign there having failed. He seized control of the French government on November 9, in a bloodless coup d'état, replacing the Directory with the Consulate and transforming the republic into a de facto dictatorship.[35] He further reorganised the French military forces, establishing a large reserve army positioned to support campaigns on the Rhine or in Italy. Russia had already been knocked out of the war, and, under Napoleon's leadership, the French decisively defeated the Austrians in June 1800, crippling Austrian capabilities in Italy. Austria was definitively defeated that December, by Moreau's forces in Bavaria. The Austrian defeat was sealed by the Treaty of Lunéville early the following year, further compelling the British to sign the Treaty of Amiens with France, establishing a tenuous peace.

Start date and nomenclature edit

No consensus exists as to when the French Revolutionary Wars ended and the Napoleonic Wars began. Possible dates include 9 November 1799, when Bonaparte seized power on 18 Brumaire, the date according to the Republican Calendar then in use;[46] 18 May 1803, when Britain and France ended the one short period of peace between 1792 and 1814; or 2 December 1804, when Bonaparte crowned himself Emperor.[47]

British historians occasionally refer to the nearly continuous period of warfare from 1792 to 1815 as the Great French War, or as the final phase of the Anglo-French Second Hundred Years' War, spanning the period 1689 to 1815.[48] Historian Mike Rapport (2013) suggested using the term "French Wars" to unambiguously describe the entire period from 1792 to 1815.[49]

In France, the Napoleonic Wars are generally integrated with the French Revolutionary Wars: Les guerres de la Révolution et de l'Empire.[50]

German historiography may count the War of the Second Coalition (1798/9–1801/2), during which Napoleon had seized power, as the Erster Napoleonischer Krieg ("First Napoleonic War").[51]

In Dutch historiography, it is common to refer to the 7 major wars between 1792 and 1815 as the Coalition Wars (coalitieoorlogen), referring to the first two as the French Revolution Wars (Franse Revolutieoorlogen).[52]

Napoleon's tactics edit

Napoleon was, and remains, famous for his battlefield victories, and historians have spent enormous attention in analysing them.[53][page needed] In 2008, Donald Sutherland wrote:

The ideal Napoleonic battle was to manipulate the enemy into an unfavourable position through manoeuvre and deception, force him to commit his main forces and reserve to the main battle and then undertake an enveloping attack with uncommitted or reserve troops on the flank or rear. Such a surprise attack would either produce a devastating effect on morale or force him to weaken his main battle line. Either way, the enemy's own impulsiveness began the process by which even a smaller French army could defeat the enemy's forces one by one.[54]

After 1807, Napoleon's creation of a highly mobile, well-armed artillery force gave artillery usage an increased tactical importance. Napoleon, rather than relying on infantry to wear away the enemy's defences, could now use massed artillery as a spearhead to pound a break in the enemy's line. Once that was achieved he sent in infantry and cavalry.[55][page range too broad]

Prelude edit

Britain was irritated by several French actions following the Treaty of Amiens. Bonaparte annexed Piedmont and Elba, made himself President of the Italian Republic, a state in northern Italy that France had set up, and failed to evacuate Holland, as it had agreed to do in the treaty. France then continued to interfere with British trade despite peace having been made and complained about Britain harbouring certain individuals and not cracking down on the anti-French press.[56]

Malta was captured by Britain during the war and was subject to a complex arrangement in the 10th article of the Treaty of Amiens, where it was to be restored to the Knights of St. John with a Neapolitan garrison and placed under the guarantee of third powers. The weakening of the Knights of St. John by the confiscation of their assets in France and Spain along with delays in obtaining guarantees prevented the British from evacuating it after three months as stipulated in the treaty.[57]

The Helvetic Republic was set up by France when it invaded Switzerland in 1798. France had withdrawn its troops, but violent strife broke out against the government, which many Swiss saw as overly centralised. Bonaparte reoccupied the country in October 1802 and imposed a compromise settlement. This caused widespread outrage in Britain, which protested that this was a violation of the Treaty of Lunéville. Although continental powers were unprepared to act, the British decided to send an agent to help the Swiss obtain supplies, and also ordered their military not to return Cape Colony to Holland as they had committed to do in the Treaty of Amiens.[58]

Swiss resistance collapsed before anything could be accomplished, and, after a month, Britain countermanded the orders to not restore Cape Colony. At the same time, Russia finally joined the guarantee regarding Malta. Concerned that there would be hostilities when Bonaparte found out that Cape Colony had been retained, the British began to procrastinate on the evacuation of Malta.[59] In January 1803, a government paper in France published a report from a commercial agent which noted the ease with which Egypt could be conquered. The British seized on this to demand satisfaction and security before evacuating Malta, which was a convenient stepping stone to Egypt. France disclaimed any desire to seize Egypt and asked what sort of satisfaction was required, but the British were unable to give a response.[60] There was still no thought of going to war; Prime Minister Henry Addington publicly affirmed that Britain was in a state of peace.[61]

In early March 1803, the Addington ministry received word that Cape Colony had been reoccupied by the British army, in accordance with the orders which had subsequently been countermanded. On 8 March they ordered military preparations to guard against possible French retaliation and justified them by falsely claiming that it was only in response to French preparations and that they were conducting serious negotiations with France. In a few days, it was known that Cape Colony had been surrendered in accordance with the counter-orders, but it was too late. Bonaparte berated the British ambassador in front of 200 spectators over the military preparations.[62]

The Addington ministry realised they would face an inquiry over their false reasons for the military preparations, and during April unsuccessfully attempted to secure the support of William Pitt the Younger to shield them from damage.[63] In the same month, the ministry issued an ultimatum to France, demanding a retention of Malta for at least ten years, the permanent acquisition of the island of Lampedusa from the Kingdom of Sicily, and the evacuation of Holland. They also offered to recognise French gains in Italy if they evacuated Switzerland and compensated the King of Sardinia for his territorial losses. France offered to place Malta in the hands of Russia to satisfy British concerns, pull out of Holland when Malta was evacuated, and form a convention to give satisfaction to Britain on other issues. The British falsely denied that Russia had made an offer, and their ambassador left Paris.[64] Desperate to avoid a war, Bonaparte sent a secret offer where he agreed to let Britain retain Malta if France could occupy the Otranto peninsula in Naples.[65] All efforts were futile, and Britain declared war on 18 May 1803.

War between Britain and France, 1803–1814 edit

British motivations edit

Britain ended the uneasy truce created by the Treaty of Amiens when it had declared war on France in May 1803. The British were increasingly angered by Napoleon's reordering of the international system in Western Europe, especially in Switzerland, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands. Kagan argues that Britain was especially alarmed by Napoleon's assertion of control over Switzerland. The British felt insulted when Napoleon said it deserved no voice in European affairs (even though King George was an elector of the Holy Roman Empire) and sought to restrict the London newspapers that were vilifying him.[36]

Britain had a sense of loss of control, as well as loss of markets, and were worried by Napoleon's possible threat to its overseas colonies. McLynn argues that Britain went to war in 1803 out of a "mixture of economic motives and national neuroses—an irrational anxiety about Napoleon's motives and intentions." McLynn concludes that it proved to be the right choice for Britain because, in the long run, Napoleon's intentions were hostile to the British national interest. Napoleon was not ready for war, and so this was the best time for Britain to stop them. Britain seized upon the Malta issue, refusing to follow the terms of the Treaty of Amiens and evacuate the island.[66]

The deeper British grievance was their perception that Napoleon was taking personal control of Europe, making the international system unstable, and forcing Britain to the sidelines.[67][68][page needed][36][page needed] Numerous scholars have argued that Napoleon's aggressive posture made him enemies and cost him potential allies.[69] As late as 1808, the continental powers affirmed most of his gains and titles, but the continuing conflict with Britain led him to start the Peninsular War and the invasion of Russia, which many scholars see as a dramatic miscalculation.[70][71][72]

There was one serious attempt to negotiate peace with France during the war, made by Charles James Fox in 1806. The British wanted to retain their overseas conquests and have Hanover restored to George III in exchange for accepting French conquests on the continent. The French were willing to cede Malta, Cape Colony, Tobago, and French Indian posts to Britain but wanted to obtain Sicily in exchange for the restoration of Hanover, a condition which the British refused.[73][page needed]

Unlike its many coalition partners, Britain remained at war during the period of the Napoleonic Wars. Protected by naval supremacy (in the words of Admiral Jervis to the House of Lords "I do not say, my Lords, that the French will not come. I say only they will not come by sea"), Britain did not have to spend the entire war defending itself and could thus focus on supporting its embattled allies, maintaining low-intensity land warfare on a global scale for over a decade. The British government paid out a large amount of money to other European states so that they could pay armies in the field against France. These payments are colloquially known as the Golden Cavalry of St George. The British Army provided long-term support to the Spanish rebellion in the Peninsular War of 1808–1814, assisted by Spanish guerrilla ('little war') tactics. Anglo-Portuguese forces under Arthur Wellesley supported the Spanish, who campaigned successfully against the French armies, eventually driving them from Spain and allowing Britain to invade southern France. By 1815, the British Army played the central role in the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo.

Beyond minor naval actions against British imperial interests, the Napoleonic Wars were much less global in their scope than preceding conflicts such as the Seven Years' War, which historians term a "world war".

Economic warfare edit

In response to the naval blockade of the French coasts enacted by the British government on 16 May 1806, Napoleon issued the Berlin Decree on November 21, 1806, which brought into effect the Continental System.[74] This policy aimed to eliminate the threat from Britain by closing French-controlled territory to its trade. Britain maintained a standing army of 220,000 at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, of whom less than 50% were available for campaigning. The rest were necessary for garrisoning Ireland and the colonies and providing security for Britain. France's strength peaked at around 2,500,000 full-time and part-time soldiers including several hundred thousand National Guardsmen whom Napoleon could draft into the military if necessary. Both nations enlisted large numbers of sedentary militia who were unsuited for campaigning and were mostly employed to release regular forces for active duty.[75]

The Royal Navy disrupted France's extra-continental trade by seizing and threatening French shipping and colonial possessions, but could do nothing about France's trade with the major continental economies, and posed little threat to French territory in Europe. France's population and agricultural capacity greatly outstripped Britain's. Britain had the greatest industrial capacity in Europe, and its mastery of the seas allowed it to build up considerable economic strength through trade. This ensured that France could never consolidate its control over Europe in peace. Many in the French government believed that cutting Britain off from the Continent would end its economic influence over Europe and isolate it.

Financing the war edit

A key element in British success was its ability to mobilise the nation's industrial and financial resources, and apply them to defeating France. Though the UK had a population of approximately 16 million against France's 30 million, the French numerical advantage was offset by British subsidies that paid for many of the Austrian and Russian soldiers, peaking at about 450,000 men in 1813.[75][76][page needed] Under the Anglo–Russian agreement of 1803, Britain paid a subsidy of £1.5 million for every 100,000 Russian soldiers in the field.[77]

British national output continued to be strong, and the well-organised business sector channeled products into what the military needed. Britain used its economic power to expand the Royal Navy, doubling the number of frigates, adding 50 per cent more large ships of the line, and increasing the number of sailors from 15,000 to 133,000 in eight years after the war began in 1793. France saw its navy shrink by more than half.[78] The smuggling of finished products into the continent undermined French efforts to weaken the British economy by cutting off markets. Subsidies to Russia and Austria kept them in the war. The British budget in 1814 reached £98 million, including £10 million for the Royal Navy, £40 million for the army, £10 million for the allies, and £38 million as interest on the national debt, which had soared to £679 million, more than double the GDP. This debt was supported by hundreds of thousands of investors and taxpayers, despite the higher taxes on land and a new income tax. The cost of the war amounted to £831 million.[aq] In contrast, the French financial system was inadequate and Napoleon's forces had to rely in part on requisitions from conquered lands.[80][page range too broad][81][page needed][82]

From London in 1813 to 1815, Nathan Mayer Rothschild was crucial in almost single-handedly financing the British war effort, organising the shipment of bullion to the Duke of Wellington's armies across Europe, as well as arranging the payment of British financial subsidies to their continental allies.[83]

War of the Third Coalition, 1805 edit

Britain gathered allies to form the Third Coalition against The French Empire after Napoleon was self-proclaimed as emperor.[85][page range too broad][86] In response, Napoleon seriously considered an invasion of Great Britain,[87][88] massing 180,000 troops at Boulogne. Before he could invade, he needed to achieve naval superiority—or at least to pull the British fleet away from the English Channel. A complex plan to distract the British by threatening their possessions in the West Indies failed when a Franco-Spanish fleet under Admiral Villeneuve turned back after an indecisive action off Cape Finisterre on 22 July 1805. The Royal Navy blockaded Villeneuve in Cádiz until he left for Naples on 19 October; the British squadron caught and overwhelmingly defeated the combined enemy fleet in the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October (the British commander, Lord Nelson, died in the battle). Napoleon never again had the opportunity to challenge the British at sea, nor to threaten an invasion. He again turned his attention to the enemies on the Continent.

In April 1805, Britain and Russia signed a treaty with the aim of removing the French from the Batavian Republic (roughly present-day Netherlands) and the Swiss Confederation. Austria joined the alliance after the annexation of Genoa and the proclamation of Napoleon as King of Italy on 17 March 1805. Sweden, which had already agreed to lease Swedish Pomerania as a military base for British troops against France, entered the coalition on 9 August.

The Austrians began the war by invading Bavaria on 8 September[89] 1805 with an army of about 70,000 under Karl Mack von Leiberich, and the French army marched out from Boulogne in late July 1805 to confront them. At Ulm (25 September – 20 October) Napoleon surrounded Mack's army, forcing its surrender without significant losses.

With the main Austrian army north of the Alps defeated (another army under Archduke Charles fought against André Masséna's French army in Italy), Napoleon occupied Vienna on 13 November. Far from his supply lines, he faced a larger Austro–Russian army under the command of Mikhail Kutuzov, with Emperor Alexander I of Russia personally present. On 2 December, Napoleon crushed the Austro–Russian force in Moravia at Austerlitz (usually considered his greatest victory). He inflicted 25,000 casualties on a numerically superior enemy army while sustaining fewer than 7,000 in his own force.

Austria signed the Treaty of Pressburg (26 December 1805) and left the coalition. The treaty required the Austrians to give up Venetia to the French-dominated Kingdom of Italy and the Tyrol to Bavaria. With the withdrawal of Austria from the war, stalemate ensued. Napoleon's army had a record of continuous unbroken victories on land, but the full force of the Russian army had not yet come into play. Napoleon had now consolidated his hold on France, had taken control of Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and most of Western Germany and northern Italy. His admirers say that Napoleon wanted to stop now, but was forced to continue in order to gain greater security from the countries that refused to accept his conquests. Esdaile rejects that explanation and instead says that it was a good time to stop expansion, for the major powers were ready to accept Napoleon as he was:

in 1806 both Russia and Britain had been positively eager to make peace, and they might well have agreed to terms that would have left the Napoleonic imperium almost completely intact. As for Austria and Prussia, they simply wanted to be left alone. To have secured a compromise peace, then, would have been comparatively easy. But Napoleon was prepared to make no concessions.[90]

War of the Fourth Coalition, 1806–1807 edit

Within months of the collapse of the Third Coalition, the Fourth Coalition (1806–1807) against France was formed by Britain, Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden. In July 1806, Napoleon formed the Confederation of the Rhine out of the many small German states which constituted the Rhineland and most other western parts of Germany. He amalgamated many of the smaller states into larger electorates, duchies, and kingdoms to make the governance of non-Prussian Germany smoother. Napoleon elevated the rulers of the two largest Confederation states, Saxony and Bavaria, to the status of kings.

In August 1806, the Prussian king, Frederick William III, decided to go to war independently of any other great power. The army of Russia, a Prussian ally, in particular, was too far away to assist. On October 8, 1806, Napoleon unleashed all the French forces east of the Rhine into Prussia. Napoleon defeated a Prussian army at Jena (14 October 1806), and Davout defeated another at Auerstädt on the same day. 160,000 French soldiers (increasing in number as the campaign went on) attacked Prussia, moving with such speed that they destroyed the entire Prussian Army as an effective military force. Out of 250,000 troops, the Prussians sustained 25,000 casualties, lost a further 150,000 as prisoners, 4,000 artillery pieces, and over 100,000 muskets. At Jena, Napoleon had fought only a detachment of the Prussian force. The battle at Auerstädt involved a single French corps defeating the bulk of the Prussian army. Napoleon entered Berlin on 27 October 1806. He visited the tomb of Frederick the Great and instructed his marshals to remove their hats there, saying, "If he were alive we wouldn't be here today". Napoleon had taken only 19 days from beginning his attack on Prussia to knock it out of the war with the capture of Berlin and the destruction of its principal armies at Jena and Auerstädt. Saxony abandoned Prussia, and together with small states from north Germany, allied with France.

In the next stage of the war, the French drove Russian forces out of Poland and employed many Polish and German soldiers in several sieges in Silesia and Pomerania, with the assistance of Dutch and Italian soldiers in the latter case. Napoleon then turned north to confront the remainder of the Russian army and to try to capture the temporary Prussian capital at Königsberg. A tactical draw at Eylau (7–8 February 1807), followed by capitulation at Danzig (24 May 1807) and the Battle of Heilsberg (10 June 1807), forced the Russians to withdraw further north. Napoleon decisively beat the Russian army at Friedland (14 June 1807), following which Alexander had to make peace with Napoleon at Tilsit (7 July 1807). In Germany and Poland, new Napoleonic client states, such as the Kingdom of Westphalia, Duchy of Warsaw, and Republic of Danzig, were established. Early that same year, the French besieged the fortified town of Kolberg, which resulted in a lifting of the siege by a peace treaty on 2 July.

By September, Marshal Guillaume Brune completed the occupation of Swedish Pomerania, allowing the Swedish army to withdraw with all its munitions of war.

edit

Britain's first response to Napoleon's Continental System was to launch a major naval attack against Denmark. Although ostensibly neutral, Denmark was under heavy French and Russian pressure to pledge its fleet to Napoleon. London could not take the chance of ignoring the Danish threat. In August 1807, the Royal Navy besieged and bombarded Copenhagen, leading to the capture of the Dano–Norwegian fleet, and assuring use of the sea lanes in the North and Baltic seas for the British merchant fleet. Denmark joined the war on the side of France, but without a fleet it had little to offer,[91][page needed][92][page needed] beginning an engagement in a naval guerrilla war in which small gunboats attacked larger British ships in Danish and Norwegian waters. Denmark also committed themselves to participate in a war against Sweden together with France and Russia.

At Tilsit, Napoleon and Alexander had agreed that Russia should force Sweden to join the Continental System, which led to a Russian invasion of Finland in February 1808, followed by a Danish declaration of war in March. Napoleon also sent an auxiliary corps, consisting of troops from France, Spain and Holland, led by Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, to Denmark to participate in the invasion of Sweden. But British naval superiority prevented the armies from crossing the Øresund strait, and the war came mainly to be fought along the Swedish–Norwegian border. At the Congress of Erfurt (September–October 1808), France and Russia further agreed on the division of Sweden into two parts separated by the Gulf of Bothnia, where the eastern part became the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland. British voluntary attempts to assist Sweden with humanitarian aid remained limited, and did not prevent Sweden from adopting a more Napoleon-friendly policy.[93][page range too broad]

The war between Denmark and Britain effectively finished with a British victory at the Battle of Lyngør in 1812, involving the destruction of the last large Dano–Norwegian ship—the frigate Najaden.

Poland edit

In 1807, Napoleon created a powerful outpost of his empire in Central Europe. Poland had recently been partitioned by its three neighbours, but Napoleon created the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, which depended on France from the beginning. The duchy consisted of lands seized by Austria and Prussia; its Grand Duke was Napoleon's ally King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, but Napoleon appointed the intendants who administered the country. The population of 4.3 million was released from occupation and, by 1814, sent about 200,000 men to Napoleon's armies. That included about 90,000 who marched with him to Moscow; few marched back.[94] The Russians strongly opposed any move towards an independent Poland and one reason Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812 was to punish them. The Grand Duchy was absorbed into the Russian Empire as a semi-autonomous Congress Poland in 1815; Poland did not become a sovereign state again until 1918, following the collapse of the neighbouring Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian Empires in the aftermath of World War I. Napoleon's impact on Poland was significant, including the Napoleonic legal code, the abolition of serfdom, and the introduction of modern middle-class bureaucracies.[95][96]

Peninsular War, 1808–1814 edit

The Iberian conflict began when Portugal continued trade with Britain, despite French restrictions. When Spain failed to maintain the Continental System, the uneasy Spanish alliance with France ended in all but name. French troops gradually encroached on Spanish territory until they occupied Madrid, and installed a client monarchy. This provoked an explosion of popular rebellions across Spain. Heavy British involvement soon followed.

After defeats in Spain suffered by France, Napoleon took charge and enjoyed success, retaking Madrid, defeating the Spanish, and forcing a withdrawal of the heavily out-numbered British army from the Iberian Peninsula (Battle of Corunna, 16 January 1809). But when he left, the guerrilla war against his forces in the countryside continued to tie down great numbers of troops. The outbreak of the War of the Fifth Coalition prevented Napoleon from successfully wrapping up operations against British forces by necessitating his departure for Austria, and he never returned to the Peninsular theatre. The British then sent in a fresh army under Sir Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington).[97][page needed] For a time, the British and Portuguese remained restricted to the area around Lisbon (behind their impregnable Lines of Torres Vedras), while their Spanish allies were besieged in Cádiz.

The Peninsular war proved a major disaster for France. Napoleon did well when he was in direct charge, but severe losses followed his departure, as he severely underestimated how much manpower would be needed. The effort in Spain was a drain on money, manpower and prestige. Historian David Gates called it the "Spanish ulcer".[98][page needed] Napoleon realised it had been a disaster for his cause, writing later, "That unfortunate war destroyed me ... All the circumstances of my disasters are bound up in that fatal knot."[99]

The Peninsular campaigns witnessed 60 major battles and 30 major sieges, more than any other of the Napoleonic conflicts, and lasted over 6 years, far longer than any of the others. France and her allies lost at least 91,000 killed in action and 237,000 wounded in the peninsula.[100] From 1812, the Peninsular War merged with the War of the Sixth Coalition.

War of the Fifth Coalition, 1809 edit

The Fifth Coalition (1809) of Britain and Austria against France formed as Britain engaged in the Peninsular War in Spain and Portugal. The sea became a major theatre of war against Napoleon's allies. Austria, previously an ally of France, took the opportunity to attempt to restore its imperial territories in Germany as held prior to Austerlitz. During the time of the Fifth Coalition, the Royal Navy won a succession of victories in the French colonies. On land the major battles included Battles of Raszyn, Eckmuhl, Raab, Aspern-Essling, and Wagram.

On land, the Fifth Coalition attempted few extensive military endeavours. One, the Walcheren Expedition of 1809, involved a dual effort by the British Army and the Royal Navy to relieve Austrian forces under intense French pressure. It ended in disaster after the Army commander, John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, failed to capture the objective, the naval base of French-controlled Antwerp. For the most part of the years of the Fifth Coalition, British military operations on land (apart from the Iberian Peninsula) remained restricted to hit-and-run operations executed by the Royal Navy, which dominated the sea after having beaten down almost all substantial naval opposition from France and its allies and blockading what remained of France's naval forces in heavily fortified French-controlled ports. These rapid-attack operations were aimed mostly at destroying blockaded French naval and mercantile shipping and the disruption of French supplies, communications, and military units stationed near the coasts. Often, when British allies attempted military actions within several dozen miles or so of the sea, the Royal Navy would arrive, land troops and supplies, and aid the coalition's land forces in a concerted operation. Royal Navy ships even provided artillery support against French units when fighting strayed near enough to the coastline. The ability and quality of the land forces governed these operations. For example, when operating with inexperienced guerrilla forces in Spain, the Royal Navy sometimes failed to achieve its objectives because of the lack of manpower that the Navy's guerrilla allies had promised to supply.

Austria achieved some initial victories against the thinly spread army of Marshal Berthier. Napoleon left Berthier with only 170,000 men to defend France's entire eastern frontier (in the 1790s, 800,000 men had carried out the same task, but holding a much shorter front).

In the east, the Austrians drove into the Duchy of Warsaw but suffered defeat at the Battle of Raszyn on 19 April 1809. The Army of the Duchy of Warsaw captured West Galicia following its earlier success. Napoleon assumed personal command and bolstered the army for a counter-attack on Austria. After a few small battles, the well-run campaign forced the Austrians to withdraw from Bavaria, and Napoleon advanced into Austria. His hurried attempt to cross the Danube resulted in the major Battle of Aspern-Essling (22 May 1809) – Napoleon's first significant tactical defeat. But the Austrian commander, Archduke Charles, failed to follow up on his indecisive victory, allowing Napoleon to prepare and seize Vienna in early July. He defeated the Austrians at Wagram, on 5–6 July. (It was during the middle of that battle that Marshal Bernadotte was stripped of his command after retreating contrary to Napoleon's orders. Shortly thereafter, Bernadotte took up the offer from Sweden to fill the vacant position of Crown Prince there. Later he actively participated in wars against his former Emperor.)

The War of the Fifth Coalition ended with the Treaty of Schönbrunn (14 October 1809). In the east, only the Tyrolese rebels led by Andreas Hofer continued to fight the French-Bavarian army until finally defeated in November 1809. In the west, the Peninsular War continued. Economic warfare between Britain and France continued: The British continued a naval blockade of French-controlled territory. Due to military shortages and lack of organisation in French territory, many breaches of the Continental System occurred and the French Continental System was largely ineffective and did little economic damage to Great Britain. Both sides entered further conflicts in attempts to enforce their blockade. As Napoleon realised that extensive trade was going through Spain and Russia, he invaded those two countries.;[101] the British fought the United States in the War of 1812 (1812–1815).

In 1810, the French Empire reached its greatest extent. Napoleon married Marie-Louise, an Austrian Archduchess, with the aim of ensuring a more stable alliance with Austria and of providing the Emperor with an heir (something his first wife, Joséphine, had failed to do). As well as the French Empire, Napoleon controlled the Swiss Confederation, the Confederation of the Rhine, the Duchy of Warsaw and the Kingdom of Italy. Territories allied with the French included:

- the kingdoms of Denmark–Norway

- the Kingdom of Spain (under Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's elder brother)

- the Kingdom of Westphalia (Jérôme Bonaparte, Napoleon's younger brother)

- the Kingdom of Naples (under Joachim Murat, husband of Napoleon's sister Caroline)

- the Principality of Lucca and Piombino (under Elisa Bonaparte (Napoleon's sister) and her husband Felice Baciocchi);

and Napoleon's former enemies, Sweden, Prussia and Austria.

Subsidiary wars edit

The Napoleonic Wars were the direct cause of wars in the Americas and elsewhere.

Serbian Revolution edit

The Serbian Revolution coincided with the Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812) (in which the French diplomat, Horace François Bastien Sébastiani de La Porta played a very important role in provoking the war), which were a proxy conflict of the Coalition Wars, having most of the time Serbs revolutionaries the support of the Russian Empire, while the Ottoman Empire was an ally of the French Empire.[102][103] This was due to the fact that both empires feared Napoleon's moves to the east as the subsequent Peace of Pressburg brought France into Balkan affairs.[104] The most radical and liberal rebels were also inspired in some way by the French Revolution (specially the rise of nationalism) and the autonomy of the Illyrian Provinces (Serbs initially felt that French presence in the region could have developed into military aid in support of the insurrection against Ottoman rule as a Sister republic, but Napoleon didn't want to increase Russian or Austrian influence in the region).[104][105]

During the first phase, from 1804 to 1806, it was a conservative reaction to new abuses by the Janissaries and Dahis, after they killed Hadyi Mustafa Pasha (vizier of the Sanjak of Smederevo. He created a militia of Serb notables and realized the Slaughter of the Knezes, because the Janissaries, expelled from Belgrade, found refuge with Osman Pazvantoğlu, governor of the Sanjak of Vidin (in present-day Bulgaria), who pursued his own policy and sought independence, which brought him into conflict with the Serbs and later with the Sublime Porte. Thus, the Serbs appealed to Sultan Selim III for assistance against the Dahis, who had since rejected the authority of the Porte. Also, Karađorđe negotiated with the Austrian captain Sajtinski. At this meeting, he expressed the wish of the Serbian people that the Austrian Empire receive him as a kingdom under his protection like in the past, as occupation of 1788–1791 was still a fresh memory. However, the Austrian authorities, due to difficulties with Napoleon and because they wanted to maintain their neutrality, in order to be correct with the Porte, could not accept his offers. So, the Serbs were forced to ask for the protection of the Russians, and therefore, on May 3, 1804, the Serb leaders sent a letter to the Russian envoy in Constantinople, in which they spoke of the problems and wishes of the Serbian people, but they also stressed that they would continue to be loyal to the Sultan. Due to the recent Russo-Ottoman alliance against France's expanding influence in the Balkans (the approach of French troops to the Turkish territories, like occupation of Corfu and other Ionian islands in 1797–99, influenced the Porte to conclude an alliance with Russia in 1798), the Russian government had a neutral policy toward the Serbian revolt until summer 1804, in which the goal was now to having Constantinople recognize Russia as the guarantor of peace in the region.[106]

In 1806, the Serbs rejected Ičko's Peace (the Ottomans seemed ready to grant Serbia autonomy, similar to that enjoyed by neighbouring Wallachia, in order to enter in the Napoleonic Wars as an ally of the French) as they desired Russian support for their independence, starting a new phase of the uprising in which the Serbs planned to create their own national state, which would also include the territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as the pashaliks of Vidin, Nis, Leskovac, and Pazar. Also, in the Traditionalist circles of Serbia rebels,[107] Petar I of Montenegro developed a plan in 1807 to restore the medieval Serbian Empire ("Slaveno–Serb empire"), consisting on unify Podgorica, Spuž, Žabljak, the Bay of Kotor, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Dubrovnik and Dalmatia with Montenegro,[108] which he informed the Russian court[108][107][109][110] and was also viewed by Habsburg Serb metropolitan Stefan Stratimirović.[111] The title of Emperor of the Serbs would be held by the Russian emperor as Tsar,[108] but with the condition that Russians respected the independence-autocephaly of the Montenegrin Orthodox Church. So, in February 1807, Petar I planned an invasion of Herzegovina by montenegrin forces and asked for Karađorđe's aid,[112] wanting to connect the territory occupied by the Serbian rebel forces and Montenegro, which succeeded after the Battle of Suvodol in 1809.[113] This support of Montenegro for the Serbs was reinforced due to the fact that in the war of 1807–1812, Ottoman troops, supported by French detachments on Illyria, attacked Montenegro along the entire border, and the Montenegrins did not have time to repel all the attacks. However, they managed to force the French troops to withdraw from Dubrovnik and conquered the Bay of Kotor. Napoleon himself offered Petar I the title "Patriarch of the entire Serbian nation or of the entire Illyricum" on the condition that he cease cooperation with Russia and accept a French protectorate, which he refused for fear of an eventual papal status jurisdiction or an Anti-clerical policy.[107][114]

However, the Treaty Of Tilsit between France and Russia against the Ottomans helped put a stop to hostilities in the Balkans, with a truce taking place (which was perceived extremely negatively in Serbia, despite the fact that the truce did not apply to the Serb rebels), also, there was a secret clause that provides for the division of Turkish possessions in the Balkans between Russia and France[115] and the cancellation of the Slaveno-Serb empire project.[108] In 1809, Karađorđe appealed to an alliance with the Habsburgs and Napoleon, with no success,[116] even wrote personally to Napoleon seeking military assistance, and in 1810, dispatched an emissary to French Empire.[117] However, the French did not believe that the rebels had the military capacity to defeat the Ottomans or expulse them from the Balkans. In 1812, under pressure from Napoleon, Russia was forced to sign the Treaty of Bucharest, which restored peace with the Ottomans.[118] One of the clauses of the treaty provided for the maintenance of Serbian autonomy, also, a truce was signed according to the Article 8 of the Treaty. Then, the Russians encouraged Karađorđe and his followers to negotiate directly with the Porte.[119][120]

War of 1812 edit

The War of 1812 coincided with the War of the Sixth Coalition. Historians in the United States and Canada see it as a war in its own right, while Europeans often see it as a minor theatre of the Napoleonic Wars. The United States declared war on Britain because of British military support for Native Americans, interference with American merchant ships, forced enlistment of American sailors into the Royal Navy, and a desire to expand its territory. France had interfered as well, and the United States had considered declaring war on France. The war ended in a military stalemate, and there were no boundary changes at the Treaty of Ghent, which took effect in early 1815 when Napoleon was on Elba.[121][page needed]

Latin American Revolutions edit

The abdication of Kings Charles IV of Spain and Ferdinand VII of Spain and the installation of Napoleon's brother as King José provoked civil wars and revolutions, leading to the independence of most of Spain's mainland American colonies. In Spanish America, many local elites formed juntas and set up mechanisms to rule in the name of Ferdinand VII, whom they considered the legitimate Spanish monarch. The outbreak of the Spanish American wars of independence in most of the empire was a result of Napoleon's destabilizing actions in Spain, and led to the rise of strongmen in the wake of these wars.[122] The defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 caused an exodus of French soldiers into Latin America, where they joined ranks with the armies of the independence movements.[123] While these officials had a role in various victories such as the Capture of Valdivia (1820), some are held responsible for significant defeats at the hands of the royalists, as was the case at the Second Battle of Cancha Rayada (1818).[123]

In contrast, the Portuguese royal family escaped to Brazil and established the court there, resulting in political stability for Portuguese America. In 1816, Brazil was proclaimed an equal part of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves, paving the way to Brazilian independence six years later.

The Haitian Revolution began in 1791, just before the French Revolutionary Wars, and continued until 1804. France's defeat resulted in the independence of Saint-Domingue and led Napoleon to sell the territory making up the Louisiana Purchase to the United States.[124]

Barbary Wars edit

During the Napoleonic Wars, the United States, Sweden, and Sicily fought against the Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean.

Invasion of Russia, 1812 edit

The Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 resulted in the Anglo–Russian War (1807–1812). Emperor Alexander I declared war on Britain after the British attack on Denmark in September 1807. British men-of-war supported the Swedish fleet during the Finnish War and won victories over the Russians in the Gulf of Finland in July 1808 and August 1809. The success of the Russian army on land, however, forced Sweden to sign peace treaties with Russia in 1809 and with France in 1810, and to join the blockade against Britain. But Franco–Russian relations would become progressively worse after 1810, and the Russian war with Britain effectively ended. In April 1812, Britain, Russia, and Sweden signed secret agreements directed against Napoleon.[125][page needed]

The central issue for both Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I was control over Poland. Each wanted a semi-independent Poland he could control. As Esdaile notes, "Implicit in the idea of a Russian Poland was, of course, a war against Napoleon."[126] Schroeder says Poland was "the root cause" of Napoleon's war with Russia, but Russia's refusal to support the Continental System was also a factor.[127]

In 1812, at the height of his power, Napoleon invaded Russia with a pan-European Grande Armée, consisting of 450,000 men (200,000 Frenchmen, and many soldiers of allies or subject areas). The French forces crossed the Niemen river on 24 June 1812. Russia proclaimed a Patriotic War, and Napoleon proclaimed a Second Polish war. The Poles supplied almost 100,000 men for the invasion force, but against their expectations, Napoleon avoided any concessions to Poland, having in mind further negotiations with Russia.[128][page needed]

The Grande Armée marched through Russia, winning some relatively minor engagements and the major Battle of Smolensk on 16–18 August. In the same days, part of the French Army led by Marshal Nicolas Oudinot was stopped in the Battle of Polotsk by the right wing of the Russian Army, under command of General Peter Wittgenstein. This prevented the French march on the Russian capital, Saint Petersburg; the fate of the invasion was decided in Moscow, where Napoleon led his forces in person.

Russia used scorched-earth tactics, and harried the Grande Armée with light Cossack cavalry. The Grande Armée did not adjust its operational methods in response.[129] This led to most of the losses of the main column of the Grande Armée, which in one case amounted to 95,000 men, including deserters, in a week.[130]

The main Russian army retreated for almost 3 months. This constant retreat led to the unpopularity of Field Marshal Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly and a veteran, Prince Mikhail Kutuzov, was made the new Commander-in-Chief by Tsar Alexander. Finally, the two armies engaged in the Battle of Borodino on 7 September,[131][page needed] in the vicinity of Moscow. The battle was the largest and bloodiest single-day action of the Napoleonic Wars, involving more than 250,000 men and resulting in at least 70,000 casualties. It was indecisive; the French captured the main positions on the battlefield but failed to destroy the Russian army. Logistical difficulties had meant that French casualties could not be replaced, unlike Russian ones.

Napoleon entered Moscow on 14 September, after the Russian Army had retreated yet again.[132] By then, the Russians had largely evacuated the city and released criminals from the prisons to inconvenience the French; the governor, Count Fyodor Rostopchin, ordered the city to be burnt.[133] Alexander I refused to capitulate, and the peace talks attempted by Napoleon failed. In October, with no sign of clear victory in sight, Napoleon began the disastrous Great Retreat from Moscow.

At the Battle of Maloyaroslavets the French tried to reach Kaluga, where they could find food and forage supplies. The replenished Russian Army blocked the road, and Napoleon was forced to retreat the same way he had come to Moscow, through the heavily ravaged areas along the Smolensk road. In the following weeks, the Grande Armée was dealt a catastrophic blow by the onset of the Russian Winter, the lack of supplies and constant guerrilla warfare by Russian peasants and irregular troops.

When the remnants of Napoleon's army crossed the Berezina River in November, only 27,000 fit soldiers survived, with 380,000 men dead or missing and 100,000 captured.[134] Napoleon then left his men and returned to Paris to prepare the defence against the advancing Russians. The campaign had effectively ended on 14 December 1812, when the last enemy troops left Russia. The Russians had lost around 210,000 men, but with their shorter supply lines, they soon replenished their armies. For every six soldiers of the Grande Armée that entered Russia, only one would make it out in fighting condition.

War of the Sixth Coalition, 1812–1814 edit

Seeing an opportunity in Napoleon's historic defeat, Prussia, Sweden and several other German states switched sides, joining Russia, the United Kingdom and others opposing Napoleon.[136][page range too broad] Napoleon vowed that he would create a new army as large as the one he had sent into Russia, and quickly built up his forces in the east from 30,000 to 130,000 and eventually to 400,000. Napoleon inflicted 40,000 casualties on the Allies at Lützen (2 May 1813) and Bautzen (20–21 May 1813). Both battles involved forces of over 250,000, making them some of the largest conflicts of the wars so far. Klemens von Metternich in November 1813 offered Napoleon the Frankfurt proposals. They would allow Napoleon to remain Emperor but France would be reduced to its "natural frontiers" and lose control of most of Italy and Germany and the Netherlands. Napoleon still expected to win the wars, and rejected the terms. By 1814, as the Allies were closing in on Paris, Napoleon did agree to the Frankfurt proposals, but it was too late and he rejected the new harsher terms proposed by the Allies.[137]

In the Peninsular War, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, renewed the Anglo-Portuguese advance into Spain just after New Year in 1812, besieging and capturing the fortified towns of Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, and crushing a French army at the Battle of Salamanca. As the French regrouped, the Anglo-Portuguese entered Madrid and advanced towards Burgos, before retreating all the way to Portugal when renewed French concentrations threatened to trap them. As a consequence of the Salamanca campaign, the French were forced to end their long siege of Cádiz and to permanently evacuate the provinces of Andalusia and Asturias.[138][page needed]

In a strategic move, Wellesley planned to move his supply base from Lisbon to Santander. The Anglo-Portuguese forces swept northwards in late May and seized Burgos. On 21 June, at Vitoria, the combined Anglo-Portuguese and Spanish armies won against Joseph Bonaparte, finally breaking French power in Spain. The French had to retreat from the Iberian peninsula, over the Pyrenees.[139][page needed]

The belligerents declared an armistice from 4 June 1813 (continuing until 13 August) during which time both sides attempted to recover from the loss of approximately a quarter of a million men in the preceding two months. During this time coalition negotiations finally brought Austria out in open opposition to France. Two principal Austrian armies took the field, adding 300,000 men to the coalition armies in Germany. The Allies now had around 800,000 front-line soldiers in the German theatre, with a strategic reserve of 350,000 formed to support the front-line operations.[137]

Napoleon succeeded in bringing the imperial forces in the region to around 650,000—although only 250,000 came under his direct command, with another 120,000 under Nicolas Charles Oudinot and 30,000 under Davout. The remaining imperial forces came mostly from the Confederation of the Rhine, especially Saxony and Bavaria. In addition, to the south, Murat's Kingdom of Naples and Eugène de Beauharnais's Kingdom of Italy had 100,000 armed men. In Spain, another 150,000 to 200,000 French troops steadily retreated before Anglo-Portuguese forces numbering around 100,000. Thus around 900,000 Frenchmen in all theatres faced around 1,800,000 coalition soldiers (including the strategic reserve under formation in Germany). The gross figures may mislead slightly, as most of the German troops fighting on the side of the French fought at best unreliably and stood on the verge of defecting to the Allies. One can reasonably say that Napoleon could count on no more than 450,000 men in Germany—which left him outnumbered about four to one.[137]

Following the end of the armistice, Napoleon seemed to have regained the initiative at Dresden (August 1813), where he once again defeated a numerically superior coalition army and inflicted enormous casualties, while sustaining relatively few. The failures of his marshals and a slow resumption of the offensive on his part cost him any advantage that this victory might have secured. At the Battle of Leipzig in Saxony (16–19 October 1813), also called the "Battle of the Nations", 191,000 French fought more than 300,000 Allies, and the defeated French had to retreat into France. After the French withdrawal from Germany, Napoleon's remaining ally, Denmark–Norway, became isolated and fell to the coalition.[140]

Napoleon then fought a series of battles in France, including the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube, but the overwhelming numbers of the Allies steadily forced him back. The Allies entered Paris on 30 March 1814. During this time Napoleon fought his Six Days' Campaign, in which he won many battles against the enemy forces advancing towards Paris. During this entire campaign, he never managed to field more than 70,000 men against more than half a million coalition soldiers. At the Treaty of Chaumont (9 March 1814), the Allies agreed to preserve the coalition until Napoleon's total defeat.[141]

Napoleon determined to fight on, even now, incapable of fathoming his fall from power. During the campaign, he had issued a decree for 900,000 fresh conscripts, but only a fraction of these materialised, and Napoleon's schemes for victory eventually gave way to the reality of his hopeless situation. Napoleon abdicated on 6 April. Occasional military actions continued in Italy, Spain, and Holland in early 1814.[141] An armistice was signed with the Allied Powers on 23 April 1814. The First Treaty of Paris, signed on 30 May 1814, officially ended the War of the Sixth Coalition.

The victors exiled Napoleon to the island of Elba and restored the French Bourbon monarchy in the person of Louis XVIII. They signed the Treaty of Fontainebleau (11 April 1814) and initiated the Congress of Vienna to redraw the map of Europe.[141]

War of the Seventh Coalition, 1815 edit

The Seventh Coalition (1815) pitted Britain, Russia, Prussia, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands and several smaller German states against France. The period known as the Hundred Days began after Napoleon escaped from Elba and landed at Cannes (1 March 1815). Travelling to Paris, picking up support as he went, he eventually overthrew Louis XVIII. The Allies rapidly gathered their armies to meet him again. Napoleon raised 280,000 men, whom he distributed among several armies. To add to the 90,000-strong standing army, he recalled well over a quarter of a million veterans from past campaigns and issued a decree for the eventual draft of around 2.5 million new men into the French army, which was never achieved. This faced an initial coalition force of about 700,000—although coalition campaign plans provided for one million front-line soldiers, supported by around 200,000 garrison, logistics and other auxiliary personnel.

Napoleon took about 124,000 men of the Army of the North on a pre-emptive strike against the Allies in Belgium.[142] He intended to attack the coalition armies before they combined, in hope of driving the British into the sea and the Prussians out of the war. His march to the frontier achieved the surprise he had planned, catching the Anglo-Dutch Army in a dispersed arrangement. The Prussians had been more wary, concentrating 75 per cent of their army in and around Ligny. The Prussians forced the Armée du Nord to fight all the day of the 15th to reach Ligny in a delaying action by the Prussian 1st Corps. He forced Prussia to fight at Ligny on 16 June 1815, and the defeated Prussians retreated in disorder. On the same day, the left wing of the Armée du Nord, under the command of Marshal Michel Ney, succeeded in stopping any of Wellington's forces going to aid Blücher's Prussians by fighting a blocking action at Quatre Bras. Ney failed to clear the cross-roads and Wellington reinforced the position. But with the Prussian retreat, Wellington too had to retreat. He fell back to a previously reconnoitred position on an escarpment at Mont St Jean, a few miles south of the village of Waterloo.

Napoleon took the reserve of the Army of the North, and reunited his forces with those of Ney to pursue Wellington's army, after he ordered Marshal Grouchy to take the right wing of the Army of the North and stop the Prussians regrouping. In the first of a series of miscalculations, both Grouchy and Napoleon failed to realise that the Prussian forces were already reorganised and were assembling at the city of Wavre. The French army did nothing to stop a rather leisurely retreat that took place throughout the night and into the early morning by the Prussians. As the 4th, 1st, and 2nd Prussian Corps marched through the town towards Waterloo, the 3rd Prussian Corps took up blocking positions across the river, and although Grouchy engaged and defeated the Prussian rearguard under the command of Lt-Gen von Thielmann in the Battle of Wavre (18–19 June) it was 12 hours too late. In the end, 17,000 Prussians had kept 33,000 badly needed French reinforcements off the field.

Napoleon delayed the start of fighting at the Battle of Waterloo on the morning of 18 June for several hours while he waited for the ground to dry after the previous night's rain. By late afternoon, the French army had not succeeded in driving Wellington's forces from the escarpment on which they stood. When the Prussians arrived and attacked the French right flank in ever-increasing numbers, Napoleon's strategy of keeping the coalition armies divided had failed and a combined coalition general advance drove his army from the field in confusion.[143]

Grouchy organised a successful and well-ordered retreat towards Paris, where Marshal Davout had 117,000 men ready to turn back the 116,000 men of Blücher and Wellington. General Vandamme was defeated at the Battle of Issy and negotiations for surrender had begun.

On arriving at Paris three days after Waterloo, Napoleon still clung to the hope of a concerted national resistance; but the temper of the legislative chambers, and of the public generally, did not favour his view. Lacking support Napoleon abdicated again on 22 June 1815, and on 15 July he surrendered to the British squadron at Rochefort. The Allies exiled him to the remote South Atlantic island of Saint Helena, where he died on 5 May 1821.

In Italy, Joachim Murat, whom the Allies had allowed to remain King of Naples after Napoleon's initial defeat, once again allied with his brother-in-law, triggering the Neapolitan War (March to May 1815). Hoping to find support among Italian nationalists fearing the increasing influence of the Habsburgs in Italy, Murat issued the Rimini Proclamation inciting them to war. The proclamation failed and the Austrians soon crushed Murat at the Battle of Tolentino (2–3 May 1815), forcing him to flee. The Bourbons returned to the throne of Naples on 20 May 1815. Murat tried to regain his throne, but after that failed, he was executed by firing squad on 13 October 1815.

The Second Treaty of Paris, signed on 20 November 1815, officially marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars.[citation needed]

Political effects edit

The Napoleonic Wars brought radical changes to Europe, but the reactionary forces returned and restored the Bourbon house to the French throne. Napoleon had succeeded in bringing most of Western Europe under one rule. In most European countries, subjugation in the French Empire brought with it many liberal features of the French Revolution including democracy, due process in courts, abolition of serfdom, reduction of the power of the Catholic Church, and demand for constitutional limits on monarchs. The increasing voice of the middle classes with rising commerce and industry meant that restored European monarchs found it difficult to restore pre-revolutionary absolutism and had to retain many of the reforms enacted during Napoleon's rule. Institutional legacies remain to this day in the form of civil law, with clearly defined codes of law—an enduring legacy of the Napoleonic Code.

France's constant warfare with the combined forces of different combinations of, and eventually all, of the other major powers of Europe for over two decades finally took its toll. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, France no longer held the role of the dominant power in Continental Europe, as it had since the times of Louis XIV, as the Congress of Vienna produced a "balance of power" by resizing the main powers so they could balance each other and remain at peace. In this regard, Prussia was restored in its former borders, and also received large chunks of Poland and Saxony. Greatly enlarged, Prussia became a permanent Great Power. In order to drag Prussia's attention towards the west and France, the Congress also gave the Rhineland and Westphalia to Prussia. These industrial regions transformed agrarian Prussia into an industrial leader in the nineteenth century.[37] Britain emerged as the most important economic power, and its Royal Navy held unquestioned naval superiority across the globe well into the 20th century.[7]

After the Napoleonic period, nationalism, a relatively new movement, became increasingly significant. This shaped much of the course of future European history. Its growth spelled the beginning of some states and the end of others, as the map of Europe changed dramatically in the hundred years following the Napoleonic Era. Rule by fiefdoms and aristocracy was widely replaced by national ideologies based on shared origins and culture. Bonaparte's reign over Europe sowed the seeds for the founding of the nation-states of Germany and Italy by starting the process of consolidating city-states, kingdoms and principalities. At the end of the war, Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden mainly as a compensation for the loss of Finland which the other coalition members agreed to, but because Norway had signed its own constitution on 17 May 1814 Sweden initiated the Swedish–Norwegian War (1814). The war was a short one taking place between 26 July – 14 August 1814 and was a Swedish victory that put Norway into a personal union with Sweden. The union was peacefully dissolved in 1905. The United Kingdom of the Netherlands created as a buffer state against France dissolved rapidly with the independence of Belgium in 1830.[144]

The Napoleonic wars also played a key role in the independence of the Latin American colonies from Spain and Portugal. The conflict weakened the authority and military power of Spain, especially after the Battle of Trafalgar. There were many uprisings in Spanish America, leading to the wars of independence. In Portuguese America, Brazil experienced greater autonomy as it now served as seat of the Portuguese Empire and ascended politically to the status of Kingdom. These events also contributed to the Portuguese Liberal Revolution in 1820 and the Independence of Brazil in 1822.[39]

The century of relative transatlantic peace, after the Congress of Vienna, enabled the "greatest intercontinental migration in human history"[145] beginning with "a big spurt of immigration after the release of the dam erected by the Napoleonic Wars."[146] Immigration inflows relative to the US population rose to record levels (peaking at 1.6 per cent in 1850–51)[147][page range too broad] as 30 million Europeans relocated to the United States between 1815 and 1914.[148]

Another concept emerged from the Congress of Vienna—that of a unified Europe. After his defeat, Napoleon deplored the fact that his dream of a free and peaceful "European association" remained unaccomplished. Such a European association would share the same principles of government, system of measurement, currency and Civil Code. One-and-a-half centuries later, and after two world wars several of these ideals re-emerged in the form of the European Union.

Military legacy edit

Enlarged scope edit

Until the time of Napoleon, European states employed relatively small armies, made up of both national soldiers and mercenaries. These regulars were highly drilled, professional soldiers. Ancien Régime armies could only deploy small field armies due to rudimentary staffs and comprehensive yet cumbersome logistics. Both issues combined to limit field forces to approximately 30,000 men under a single commander.

Military innovators in the mid-18th century began to recognise the potential of an entire nation at war: a "nation in arms".[149]

The scale of warfare dramatically enlarged during the Revolutionary and subsequent Napoleonic Wars. During Europe's major pre-revolutionary war, the Seven Years' War of 1756–1763, few armies ever numbered more than 200,000 with field forces often numbering less than 30,000. The French innovations of separate corps (allowing a single commander to efficiently command more than the traditional command span of 30,000 men) and living off the land (which allowed field armies to deploy more men without requiring an equal increase in supply arrangements such as depots and supply trains) allowed the French republic to field much larger armies than their opponents. Napoleon ensured during the time of the French republic that separate French field armies operated as a single army under his control, often allowing him to substantially outnumber his opponents. This forced his continental opponents to also increase the size of their armies, moving away from the traditional small, well-drilled Ancien Régime armies of the 18th century to mass conscript armies.

The Battle of Marengo, which largely ended the War of the Second Coalition, was fought with fewer than 60,000 men on both sides. The Battle of Austerlitz which ended the War of the Third Coalition involved fewer than 160,000 men. The Battle of Friedland which led to peace with Russia in 1807 involved about 150,000 men.

After these defeats, the continental powers developed various forms of mass conscription to allow them to face France on even terms, and the size of field armies increased rapidly. The Battle of Wagram of 1809 involved 300,000 men, and 500,000 fought at Leipzig in 1813, of whom 150,000 were killed or wounded.

About a million French soldiers became casualties (wounded, invalided or killed), a higher proportion than in the First World War. The European total may have reached 5,000,000 military deaths, including disease.[150][151][verification needed]

France had the second-largest population in Europe by the end of the 18th century (28 million, as compared to Britain's 12 million and Russia's 35 to 40 million).[152][page range too broad] It was well poised to take advantage of the levée en masse. Before Napoleon's efforts, Lazare Carnot played a large part in the reorganisation of the French Revolutionary Army from 1793 to 1794—a time which saw previous French misfortunes reversed, with Republican armies advancing on all fronts.

The French army peaked in size in the 1790s with 1.5 million Frenchmen enlisted although battlefield strength was much less. Haphazard bookkeeping, rudimentary medical support and lax recruitment standards ensured that many soldiers either never existed, fell ill or were unable to withstand the physical demands of soldiering.

About 2.8 million Frenchmen fought on land and about 150,000 at sea, bringing the total for France to almost 3 million combatants during almost 25 years of warfare.[22]

Britain had 750,000 men under arms between 1792 and 1815 as its army expanded from 40,000 men in 1793[citation needed] to a peak of 250,000 men in 1813.[19] Over 250,000 sailors served in the Royal Navy. In September 1812, Russia had 900,000 enlisted men in its army, and between 1799 and 1815 2.1 million men served in its army. Another 200,000 served in the Imperial Russian Navy. Out of the 900,000 men, the field armies deployed against France numbered less than 250,000.