Summary

A gas engine is an internal combustion engine that runs on a fuel gas (a gaseous fuel), such as coal gas, producer gas, biogas, landfill gas, natural gas or hydrogen. In the United Kingdom and British English-speaking countries, the term is unambiguous. In the United States, due to the widespread use of "gas" as an abbreviation for gasoline (petrol), such an engine is sometimes called by a clarifying term, such as gaseous-fueled engine or natural gas engine.

Generally in modern usage, the term gas engine refers to a heavy-duty industrial engine capable of running continuously at full load for periods approaching a high fraction of 8,760 hours per year, unlike a gasoline automobile engine, which is lightweight, high-revving and typically runs for no more than 4,000 hours in its entire life. Typical power ranges from 10 kW (13 hp) to 4 MW (5,364 hp).[1]

History edit

Lenoir edit

There were many experiments with gas engines in the 19th century, but the first practical gas-fuelled internal combustion engine was built by the Belgian engineer Étienne Lenoir in 1860.[2] However, the Lenoir engine suffered from a low power output and high fuel consumption.

Otto and Langen edit

Lenoir's work was further researched and improved by a German engineer Nicolaus August Otto, who was later to invent the first four-stroke engine to efficiently burn fuel directly in a piston chamber. In August 1864 Otto met Eugen Langen who, being technically trained, glimpsed the potential of Otto's development, and one month after the meeting, founded the first engine factory in the world, NA Otto & Cie, in Cologne. In 1867 Otto patented his improved design and it was awarded the Grand Prize at the 1867 Paris World Exhibition. This atmospheric engine worked by drawing a mixture of gas and air into a vertical cylinder. When the piston has risen about eight inches, the gas and air mixture is ignited by a small pilot flame burning outside, which forces the piston (which is connected to a toothed rack) upwards, creating a partial vacuum beneath it. No work is done on the upward stroke. The work is done when the piston and toothed rack descend under the effects of atmospheric pressure and their own weight, turning the main shaft and flywheels as they fall. Its advantage over the existing steam engine was its ability to be started and stopped on demand, making it ideal for intermittent work such as barge loading or unloading.[3]

Four-stroke engine edit

The atmospheric gas engine was in turn replaced by Otto's four-stroke engine. The changeover to four-stroke engines was remarkably rapid, with the last atmospheric engines being made in 1877. Liquid-fuelled engines soon followed using diesel (around 1898) or gasoline (around 1900).

Crossley edit

The best-known builder of gas engines in the United Kingdom was Crossley of Manchester, who in 1869 acquired the United Kingdom and world (except German) rights to the patents of Otto and Langen for the new gas-fuelled atmospheric engine. In 1876 they acquired the rights to the more efficient Otto four-stroke cycle engine.

Tangye edit

There were several other firms based in the Manchester area as well. Tangye Ltd., of Smethwick, near Birmingham, sold its first gas engine, a 1 nominal horsepower two-cycle type, in 1881, and in 1890 the firm commenced manufacture of the four-cycle gas engine.[4]

Preservation edit

The Anson Engine Museum in Poynton, near Stockport, England, has a collection of engines that includes several working gas engines, including the largest running Crossley atmospheric engine ever made.

Current manufacturers edit

Manufacturers of gas engines include Hyundai Heavy Industries, Rolls-Royce with the Bergen-Engines AS, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Liebherr, MTU Friedrichshafen, INNIO Jenbacher, Caterpillar Inc., Perkins Engines, MWM (founded as Motorfahrzeug- und Motoren-Werke Mannheim AG in 1909 by Carl Benz),[5] Cummins, Wärtsilä, INNIO Waukesha, Guascor Energy , Deutz, MTU, MAN, Scania AB, Fairbanks-Morse, Doosan, Eaton (successor to another former large market share holder, Cooper Industries), and Yanmar. Output ranges from about 10 kW (13 hp) micro combined heat and power (CHP) to 18 MW (24,000 hp).[6] Generally speaking, the modern high-speed gas engine is very competitive with gas turbines up to about 50 MW (67,000 hp) depending on circumstances, and the best ones are much more fuel efficient than the gas turbines. Rolls-Royce with the Bergen Engines, Caterpillar and many other manufacturers base their products on a diesel engine block and crankshaft. INNIO Jenbacher and Waukesha are the only two companies whose engines are designed and dedicated to gas alone.

Typical applications edit

Stationary edit

Typical applications are base load or high-hour generation schemes, including combined heat and power (for typical performance figures see[7]), landfill gas, mines gas, well-head gas and biogas, where the waste heat from the engine may be used to warm the digesters. For typical biogas engine installation parameters see.[8] For parameters of a large gas engine CHP system, as fitted in a factory, see.[9] Gas engines are rarely used for standby applications, which remain largely the province of diesel engines. One exception to this is the small (<150 kW) emergency generator often installed by farms, museums, small businesses, and residences. Connected to either natural gas from the public utility or propane from on-site storage tanks, these generators can be arranged for automatic starting upon power failure.

Transport edit

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) engines are expanding into the marine market, as the lean-burn gas engine can meet the new emission requirements without any extra fuel treatment or exhaust cleaning systems. Use of engines running on compressed natural gas (CNG) is also growing in the bus sector. Users in the United Kingdom include Reading Buses. Use of gas buses is supported by the Gas Bus Alliance[10] and manufacturers include Scania AB.[11]

Use of gaseous methane or propane edit

Since natural gas, chiefly methane, has long been an economical and readily available fuel, many industrial engines are either designed or modified to use gas, as distinguished from gasoline. Their operation produces less complex-hydrocarbon pollution, and the engines have fewer internal problems. One example is the liquefied petroleum gas, chiefly propane. engine used in vast numbers of forklift trucks. Common United States usage of "gas" to mean "gasoline" requires the explicit identification of a natural gas engine. There is also such a thing as "natural gasoline",[12] but this term, which refers to a subset of natural gas liquids, is very rarely observed outside the refining industry.

Technical details edit

Fuel-air mixing edit

A gas engine differs from a petrol engine in the way the fuel and air are mixed. A petrol engine uses a carburetor or fuel injection. but a gas engine often uses a simple venturi system to introduce gas into the air flow. Early gas engines used a three-valve system, with separate inlet valves for air and gas.

Exhaust valves edit

The weak point of a gas engine compared to a diesel engine is the exhaust valves, since the gas engine exhaust gases are much hotter for a given output, and this limits the power output. Thus, a diesel engine from a given manufacturer will usually have a higher maximum output than the same engine block size in the gas engine version. The diesel engine will generally have three different ratings — standby, prime, and continuous, a.k.a. 1-hour rating, 12-hour rating and continuous rating in the United Kingdom, whereas the gas engine will generally only have a continuous rating, which will be less than the diesel continuous rating.

Ignition edit

Various ignition systems have been used, including hot-tube ignitors and spark ignition. Some modern gas engines are essentially dual-fuel engines. The main source of energy is the gas-air mixture but it is ignited by the injection of a small volume of diesel fuel.

Energy balance edit

Thermal efficiency edit

Gas engines that run on natural gas typically have a thermal efficiency between 35-45% (LHV basis).,[13] As of year 2018, the best engines can achieve a thermal efficiency up to 50% (LHV basis).[14] These gas engines are usually medium-speed engines Bergen Engines Fuel energy arises at the output shaft, the remainder appears as waste heat.[9] Large engines are more efficient than small engines. Gas engines running on biogas typically have a slightly lower efficiency (~1-2%) and syngas reduces the efficiency further still. GE Jenbacher's recent J624 engine is the world's first high efficiency methane-fueled 24-cylinder gas engine.[15]

When considering engine efficiency one should consider whether this is based on the lower heating value (LHV) or higher heating value (HHV) of the gas. Engine manufacturers will typically quote efficiencies based on the lower heating value of the gas, i.e. the efficiency after energy has been taken to evaporate the intrinsic moisture within the gas itself. Gas distribution networks will typically charge based upon the higher heating value of the gas. i.e., total energy content. A quoted engine efficiency based on LHV might be say 44% whereas the same engine might have an efficiency of 39.6% based on HHV on natural gas. It is also important to ensure that efficiency comparisons are on a like-for-like basis. For example, some manufactures have mechanically driven pumps whereas other use electrically driven pumps to drive engine cooling water, and the electrical usage can sometimes be ignored giving a falsely high apparent efficiency compared to the direct drive engines.

Combined heat and power edit

Engine reject heat can be used for building heating or heating a process. In an engine, roughly half the waste heat arises (from the engine jacket, oil cooler and after-cooler circuits) as hot water, which can be at up to 110 °C. The remainder arises as high-temperature heat which can generate pressurised hot water or steam by the use of an exhaust gas heat exchanger.

Engine cooling edit

Two most common engine types are an air-cooled engine or water cooled engine. Water cooled nowadays use antifreeze in the internal combustion engine

Some engines (air or water) have an added oil cooler.

Cooling is required to remove excessive heat, as overheating can cause engine failure, usually from wear, cracking or warping.

Gas consumption formula edit

The formula shows the gas flow requirement of a gas engine in norm conditions at full load.

where:

- is the gas flow in norm conditions

- is the engine power

- is the mechanical efficiency

- LHV is the Low Heating Value of the gas

Gallery of historic gas engines edit

- Historic Gas Engines

-

1905 National company's ordinary gas engine of 36 hp

-

1903 Körting gas engine

-

Backus upright gas engine

-

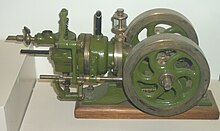

Otto horizontal gas engine

-

Otto vertical gas engine

-

Westinghouse gas engine

-

Crossley gas engine and dynamo

-

Premier twin gas engine electric generating plant

-

125 hp gas engine and dynamo

-

Crossley Brothers Ltd., 1886 No. 1 Engine, 4.5 hp single cylinder, 4-stroke gas engine, 160 rpm.

-

1915 Crossley Gas Engine (type GE130 No75590), 150 hp.

-

National Gas Engine

-

Premier tandem scavenging high-power gas engine

-

Blast furnace gas engine with blowing cylinder

-

Stockport gas engine and belt-driven dynamo

See also edit

References edit

- ^ "GE Jenbacher | Gas engines". Clarke-energy.com. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ^ "start your engines! — gas-engines". Library.thinkquest.org. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ^ "Crossley Atmospheric Gas Engine" (PDF). Museum of Science and Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ "The Basic Industries of Great Britain by Aberconway — Chapter XXI". Gracesguide.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ^ Waldauf, Daniel (2023-10-23). "Who was Carl Benz?". Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ "Gas engines at Wärtsilä". Wartsila.com. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ^ Andrews, Dave (2014-04-23). "Finning Caterpillar Gas Engine CHP Ratings | Claverton Group". Claverton-energy.com. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ^ Andrews, Dave (2008-10-14). "38% HHV Caterpillar Bio-gas Engine Fitted to Sewage Works | Claverton Group". Claverton-energy.com. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ^ a b Andrews, Dave (2010-06-24). "Complete 7 MWe Deutz (2 x 3.5MWe) gas engine CHP system for sale and re-installation in the country of your choice. Similar available on biogas / digester gas | Claverton Group". Claverton-energy.com. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ^ "Global CNG Solutions Ltd — Gas Alliance Group". Globalcngsolutions.com. Archived from the original on 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ^ "The UK's first Scania-ADL gas-powered buses delivered to Reading Buses". scania.co.uk. 2013-04-23. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ^ "Glossary — U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- ^ "CHP | Cogeneration | GE Jenbacher | Gas Engines". Clarke Energy. Archived from the original on 2012-04-30. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ^ "Rolls-Royce introducing new B36:45 gas engines to US market; up to 50% efficiency". Green Car Congress. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- ^ "Products & Services". Ge-energy.com. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

External links edit

- Crossley Gas Engine

- Antique Stationary Engines

- Old Engines

- Gas Engine Articles

- Gas Engine Magazine — An internal combustion historical magazine

- Clerk, Dugald (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). pp. 495–501.