Summary

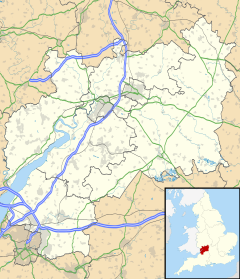

Leonard Stanley, or Stanley St.Leonard, is a village and parish in Gloucestershire, England, 95 miles (150 km) west of London and 3.5 miles (5.5 km) southwest of the town of Stroud. Situated beneath the Cotswold escarpment overlooking the Severn Vale, the surrounding land is mainly given over to agricultural use. The village is made up of some 600 houses and has an estimated population of 1,545 as of 2019.[2] The hamlet of Stanley Downton lies less than a mile to the north and lies within the parish. In 1970, the village was twinned with the commune of Dozulé in the Calvados region of Normandy, northern France.[3]

| Leonard Stanley | |

|---|---|

| |

Leonard Stanley Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 1,466 [1] |

| OS grid reference | SO 80388 03653 |

| Shire county | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Stonehouse |

| Postcode district | GL10 |

| Dialling code | 01453 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Originally a Saxon village, a priory dedicated to St. Leonard was founded in c.1130.[4] As the village grew, Leonard Stanley developed into a busy weaving and agricultural centre with inns, a marketplace, and two annual fairs.[5] Whilst agricultural usage continues, in recent years the village has become a dormitory village for the nearby towns and cities. The last village shop and post office closed in the early 2000s.

Local Geography edit

The underlying geology of the area is blue lias that was laid down during the Jurassic and Triassic periods.[6]

The parish is roughly triangular in shape. The northern boundary runs along the southern branch of the River Frome at a level of 100 feet (30 m). The Bitton Brook runs northward towards the River Frome and forms a shallow combe in the north part of the parish. To the south the tip of the parish rises up to 650 feet (200 m) at Sandford's Knoll. A nature reserve, Five Acre Grove, lies to the west of the village. It is designated as a Key Wildlife Site.[7]

Transport edit

There is a regular bus service, operated by Stagecoach West, which connects Leonard Stanley to Stroud and other local communities as well as the cities of Cheltenham and Gloucester.

The nearby railway stations of Stonehouse and Stroud are on the Cheltenham to London mainline with GWR providing a regular service to Paddington and Cheltenham Spa stations. Cam and Dursley station, situated 3 miles (5 km) west of Leonard Stanley, provides further regular mainline train services to Bristol and Birmingham.

By road, Junction 13 of the M5 lies 3 miles (5 km) northwest of the village.

The nearest coach services run from Stroud coach station.

History edit

What once had been described as a market town, "Leonard Stanley with its fairs and its weekly market, for some time the only one in the hundred, was formerly a centre of trade; it was described as a market-town in 1650. It declined in importance after the 17th century, and the beginning of the decline was later associated with the fire of 1686."[8]

Prehistoric edit

During the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras, the Severn Valley was covered by dense forest. There is evidence of a small Mesolithic community living in the area and a collection of surface flints has been discovered just to the northwest of Leonard Stanley on a forty-acre area of gravel. Finds include Mesolithic tools, scrapers, and triangular points.[9]

Roman edit

At nearby Frocester there was a significant Roman settlement which included a villa.[10] There is some evidence of the Romano-British occupation from the 3rd and 4th centuries in Leonard Stanley with small archeological finds near Seven Waters.

Norman edit

In 1086, the Domesday book records the village name as Stanlege,[11] a word derived from the Norse, meaning a stony forest or glade clearing. There were two Saxon landowners or tenants at the time of the conquest, Godric and Wisnod, who it is thought may have been brothers.[12] The settlement consisted of 25 households placing it, by size, in the top 40% in the country. By 1086, the Saxon lords had been dispossessed of their lands and Ralph de Berkeley appointed as Lord and chief tenant. Stanlege was a significant settlement lying within the administrative area of the hundred of Blacklowe which by 1220 had been incorporated into the larger hundred of Whitstone.

By 1116 a small church dedicated to St. Leonard had been built and in c.1130, Roger de Berkeley, II, founded an Augustinian Priory. The new building was sited close to the old church on rising ground above Seven Waters, and building work began in c.1131. This included the construction of a priory church also dedicated to St. Leonard which served both as the collegiate church and parochial church for the village. The priory church is a grade 1 listed building and remains in use today as the parish church of St. Swithun's.

In 1146, the priory was appropriated by Gloucester Abbey and became a Benedictine cell until its dissolution in 1538. Over the years the village became known by various names including Stanley St. Leonard, Stanley Monochorum and Monk's Stanley. In recent years it is sometimes known as Stanley St. Leonards but most commonly as Leonard Stanley.

Tudor edit

In the early 14th century Edward II granted a charter for a weekly market which was subsequently renewed by James I in 1620.[13] The market was held on Saturdays at the marketplace near, to what is now, the village green. The village held two annual fairs, one on the first Saturday after St. Swithin's Day, July 15, and the second on November 6, St Leonard's Day. It has been suggested that whilst the collegiate part the church was dedicated to St. Leonard the parochial part had a separate dedication to St. Swithin. Though there is no clear evidence for this, or any dedication to St. Swithin, it could explain why the church is today known as St. Swithun's and why the saint's day was celebrated.

In August 1535, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn spent almost the entire month in Gloucestershire. After staying at Gloucester Abbey, the king travelled to Leonard Stanley arriving there on 6 August 1535.[14] After visiting the priory and staying overnight, he and his court then travelled on to Berkeley the following day.[15] It was three years later, on 11 June 1538, that Henry sent an imperative request to the Abbot of Gloucester to recall the monks from Stanley St Leonard. The priory was dissolved and a ninety nine-year lease with an annual rent of £20 was granted to Sir William Kingston in September 1538.

Stuart and Georgian edit

By the 1600s, Leonard Stanley was a busy market town with a thriving cloth industry. The market house stood near the village green, and a fulling mill used for the cleaning of cloth had been built near the complex of fishponds at Seven Waters. The main village was situated along The Street, a road running from the priory church to the Bath Road. Farming and the clothing industry were the main employment for the villagers. Wealthy clothing families bought up land in and around Leonard Stanley. The Grange, previously known as Townsend House, was the first stone-built house in the village and stands at the junction of The Street and Bath Road. It was built for the wealthy clothier Richard Clutterbuck and dates from 1583. In 1549, another wealthy clothier, John Sandford, purchased the estates of Leonard Stanley Priory which included Priory House Farm.[16]

In the early afternoon of 23 March 1686, a catastrophic fire destroyed most of the wood-framed buildings to the west of The Street. The fire was such a significant event that King James II issued an appeal for money for rebuilding work. Many villagers were affected and lost their homes, stables and possessions reducing them to poverty.

Other houses suffered less severe damage. Lavender Cottage and Yew Tree House, both standing near the corner of the village green, underwent extensive rebuilding in the 17th century suggesting they too had suffered some damaged from the fire.[17] A few of the older buildings on The Street did survive including The Mercer's House, Weavers Cottage, Vine Cottage and Chapel House. The Mercer's House, dating from 1392, was originally a single house of cruck frame timber construction, the beams filled with wattle and daub. By the 16th century it had been extended into three houses which were attached. By 1559, part of the building included a thatched weaver's shop with two looms.

Little of the money raised for rebuilding work ever reached Leonard Stanley. Most was diverted for other pressing needs created by the ongoing civil upheavals which eventually led to the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688. Less than a sixth of the funds reached the village. This significantly impacted the community, and the village never fully recovered with the market house being in a state of dilapidation by the 1770s.

Following the fire, some building work did occur. Church Farm was built in 1688 on Church Road. On the frontage are the initials “JS”, probably a later relative of John Sandford who had bought the land in 1549. Grain and cloth were stored in the upper floors of the building. The oval windows seen near the top of the gables were left unglazed to encourage owls to nest in the building. The owl windows were a method of pest control reducing the number of mice and rats.

Priory House Farm was rebuilt in the early 17th century replacing an earlier building on the same site. The owner, another John Sandford, made significant alterations in 1750 which included an imposing new façade with a carved pediment of the Sandford coat-of-arms.[4] Also of interest near the farmhouse is a brick privy dating from the 18th century. The privy is double seated and sited over a small stream, later to be sketched by Stanley Spencer.

The building now known as Tannery House was built in 1770 for the surgeon James Clutterbuck and is situated at the corner of Church Road and Bath Road.[17] The nearby Brookside Cottage,[18] dating from the late 17th century, was originally more than one dwelling that formed part of Tannery Cottages. On the opposite side of the Bath Road, numbers 2 and 4 both date from the early 17th century. On Church Road, the houses now known as Church View and Stoneleigh previously formed the Cross Keys Inn, first mentioned in 1707. The Inn was a meeting place for both the local Clothworkers Society [16] and the church clergy who assembled there before a service at the church.[17] The brick outline of the archway to the inn is still visible. At the other end of the row of cottages is Ivy Cottage, an example of a clothiers cottage, dating from the late 16th or early 17th century. The only inn now remaining in the village is the White Hart which was first mentioned in 1740. Adjoining it and to the right is the old Parsonage today known as Rhymney Cottage.

By 1632, in Stanley Downton, a corn mill was in operation on the southern channel of the river Frome. This was Stradlyngs or Lye's mill and by the early 18th century there were seven houses at Stanley Downton together with the Flag Inn built in 1700.

The Methodist minister, Charles Wesley, visited the village and preached beneath a large elm tree on Monday, 27 August 1739.[19] The exact location of the elm tree is not recorded in his journal though oral tradition has it that the tree once stood at the junction of Church Road and Bath Road. This spot is known locally as Wesley's tump and a nearby road is named Wesley Road.

John Wesley, Charles's brother, and the founder of Methodism also preached at Leonard Stanley. On the afternoon of Sunday, 7 October 1739, he spoke for over two hours to a large crowd of about three thousand people ‘at Stanley on a little green near the town’.[20] It is thought that this was the same spot from which his brother Charles spoke a few months earlier. A thunderstorm took place during the sermon, though apparently, the crowd was not deterred and stayed through to the end.

The last member of the Sandford family to live in the village died in 1765 with the estate passing on to Robert Timbrell of Kemble who had married a Miss Sandford. The vicarage was built in 1783 and a Wesleyan Chapel, offset slightly from The Street, opened in 1818.

By this time significant technological improvements were being made in industrial mechanisation and transportation. After years of opposition by the mill owners, in July 1779 the Stroudwater Navigation, a canal, opened linking Stroud to the River Severn. Mechanisation of the cloth making process signalled the end of the cottage weaving industry with the construction of Stanley Mills in 1813.

Victorian to Modern edit

The first village school opened in the early 1800s with 14 children attending. Some years later, the charity school joined with a new national school and the first modern school building opened in 1850 for 53 pupils. With a new workhouse opening in Stroud in 1837, the village poor house became redundant and closed. Local transport improved with the opening of the Bristol to Gloucester railway in 1844. This rail link, with a station in Frocester, made it easier for transporting livestock to the Gloucester markets.[21]

Several other new businesses opened in the village; The Lamb Inn on Marsh Road in 1863, the post office on the Bath Road in 1870, and a water powered tannery in c.1848, that made leather horse harnesses.[22] The Wesleyan Chapel was extended to include a school room. Opposite the Lamb Inn at the corner of Marsh Road and Bath Road, Thomas Lidiatt, a local carpenter,[23] founded an organ and harmonium building business which made some 40 church organs over the years.[24][25]

The first census of 1801 divided the population into those 'chiefly employed in agriculture', those 'chiefly employed in trade, manufacturers or handicraft', and others. From 1841 onwards, information was gathered on each person's occupation forming a detailed data set. By 1881 a more organised classification was used in the county level tables covering 414 categories. This information is displayed as a table on the right of the page.[26] The figures show that despite the loss of the cottage weaving industry in the village, textiles along with agriculture, and domestic service were the predominant occupations.

In 1910, nearby Stonehouse had the benefit of being connected to a mains gas supply but, despite repeated requests by the parish, Leonard Stanley did not receive gas until 1926 and electricity until 1933. By now the main employment for the villagers was at the local mills, the Stonehouse brush factory, and Dudbridge foundry.[17]

During the second world war there was an influx of new residents. This included children evacuated from cities for safety away from the bombing raids and members of the land army who assisted farmers with food production for the war effort. The shadow factories in Stonehouse [27] produced armaments and provided additional employment resulting in the Stonehouse population nearly tripling over the war years. A number of those billeted in the village settled in the area after the war was over.

Post war, the village underwent considerable change. The orchards and fields rapidly disappeared making way for new housing developments. With improvements in transport, together with social changes, villagers shopping habits also changed resulting in the closure of local shops. The last loaf of bread was baked at the village bakery in the 1960s; two shops and the butchers closed during the 1970s; and, in the early 2000s, the Post Office and the village shop on Marsh Road were the last to close. In 2019, a new vending machine service opened at Church Farm selling locally made produce.[17]

Population edit

Prior to the census of 1801, population figures are estimations based on parish and other records. Between 1612 and 1712, additional information is available from resident lists. Some early surveys do exist. These include the 1087 record in Domesday, and a record in 1327 of nine people being assessed for taxes. The diocese also carried out a census of communicants in the parish in the early 16th century.

In 1551, the last major outbreak of the disease known as the Sweating Sickness struck England resulting in an estimated 15% reduction in the population. The Cotswolds was badly affected, and Leonard Stanley experienced a loss of 36.5%.[28] Following this epidemic there was a slight recovery in numbers, but by 1676 there had been an overall decline of -8.9% to 319 villagers. By 1710, the Leonard Stanley had 90 houses and 400 inhabitants. The parish records, and census information provide a much more accurate picture from 1801 onwards.

The census figures for 1801 records there were 590 villagers living in Leonard Stanley giving an overall estimated growth rate of 68% for the years between 1551 and 1801. This was considerably less than in the surrounding towns and villages with King's Stanley growing by 671% over the same period.[16]

The fire of 1686 caused considerable structural damage to the village but there was little, if any, loss of life. There must have been a financial impact on the community but how significant this was is unclear particularly as the population appears to have already been in a slight decline prior to the fire.

It is also unclear what impact mechanisation of the clothing industry had, particularly with the opening of King's Stanley Mills in 1813.[30] King's Stanley Mills was initially water powered and later used steam powered looms. Whilst this must have significantly affected the cottage weavers, the mills would also have provided other opportunities for employment and the population rose to 861 by 1851 but fell to 651 by the 1911 census.

It was after WW2 that the next significant population increase occurred. This coincided with the post war housing boom and new housing developments in the village.

Currently the village has an estimated population of 1,545 as of 2019.[2]

Housing edit

The first census to report on how well people were housed was that of 1891, but the only statistics gathered were on the number of rooms and the number of people in each household. From 1951 onwards, more questions were asked about 'amenities', meaning specific facilities that households either possessed or had shared access to.[31] Housing hadn't been an issue for Leonard Stanley since census' were first conducted; total housing flat lining from 1841 (earliest figures) 202 and a change between 1 - 2 houses from then until 1901 when there was a decline in housing, a drop to 193.

The decline continued until 1951 when there was a rapid increase in housing, jumping to 229 and a larger jump to 365 in 1961.[32] As of 2019 the village has an estimated population of 1,545 with 600 houses.[2]

Governance edit

The village falls in 'The Stanleys' electoral ward. This ward runs east–west from King's Stanley to Frocester. The total ward population at the 2011 census was 3,960.[33] Leonard Stanley is represented by the county councillor for Dursley division and the two district councillors for The Stanleys ward on Stroud District Council.

Notable people edit

- The painter Stanley Spencer lodged in Leonard Stanley from 1939 to 1941 and the village inspired scenes in some of his famous artworks.[34]

- Vice-Admiral Herbert Edward Holmes à Court, who died in 1934, is buried in the village.[35]

- Rev Charles Swynnerton, antiquary and author. Vicar of Leonard Stanley 1912-1921 and largely responsible for the restoration work carried out on St. Swithun's church.

Bibliography edit

- David Verey, Gloucestershire: the Cotswolds, The Buildings of England edited by Nikolaus Pevsner, 2nd ed. (1979) ISBN 0-14-071040-X, pp. 296–299

- Verey and Brooks The buildings of England Gloucestershire 1: The Cotswolds, 2002, Yale Press ISBN 9780300096040

- David Verey Cotswold Churches, 2007, Nonsuch Publlishing ISBN 9781845880286

- Anne Orzen The Village of Leonard Stanley (Gloucestershire), 1980

References edit

- ^ 2011 UK census

- ^ a b c "Local Insight profile for 'Leonard Stanley CP' area". gloucestershire.gov.uk. January 2019.

- ^ "Twin Towns". Leonard Stanley Parish Council. April 2018.

- ^ a b Verey and Brooks (2002). The Buildings of England. Gloucestershire 1: The Cotswolds. Yale University Press. pp. 444–447. ISBN 9780300096040.

- ^ The National Gazetter. 1868.

- ^ "British Geological Survey". 2015.

- ^ Cotswold District Local Plan, Appendix 2, Key Wildlife Sites Archived 13 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Leonard Stanley: Introduction | British History Online".

- ^ Gracie, H.S (1938). "Surface Flints from Leonard Stanley". Bristol and Gloucestershire Archeological Society. 60: 180 to 189.

- ^ Price, Eddie (2000). Frocester. A Romano-British Settlement, its Antecedents and Successors. Gloucester and District Archeological Research Group. ISBN 0953791807.

- ^ Domesday Book - First Folio - Gloucestershire. 1087. p. 13.

- ^ Swynnerton, Charles (1922). "Stanley St. Leonards". Bristol and Gloucestershire Archeological Society. 44: 221 to 269.

- ^ Rudder, Samuel (1779). A New History of Gloucestershire. pp. 685–688.

- ^ Holinshed, Mark. Henry VIII the Reign - a new look.

- ^ Historical Manuscripts Commission, 12th Report, Appendix 9: Gloucester (London, 1891), p. 444.

- ^ a b c Hudson, Janet (1998). "Residence and kinship in a clothing community : Stonehouse 1558-1804". Thesis: 108–173.

- ^ a b c d e f Orzen, Anne (1980). The Village of Leonard Stanley (Gloucestershire). p. 15.

- ^ National Heritage List for England

- ^ Charles Wesley, The Journal of the Rev. Charles Wesley (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1849)

- ^ Wesley, John (1951). The Journal of John Wesley. Moody Press. p. 46.

- ^ GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, History of Leonard Stanley, in Stroud and Gloucestershire | Map and description, A Vision of Britain through Time.

- ^ Mills, Stephen (1991). "Leonard Stanley Tannery - A preliminary Report". Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology. 1991 Journal: 2–12.

- ^ Verey, David (2007). Cotswold Churches. Nonsuch. p. 147. ISBN 9781845880286.

- ^ Cadbury Research Library (2021). "Hand list to the British Organ Archive". Birmingham University.

- ^ Verey & Brooks (2002). Gloucestershire 1: The Cotswolds. Yale University Press. p. 430. ISBN 9780300096040.

- ^ http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10032570/theme/IND

- ^ Dickenson, Jim (May 2012). "Hoffmann's shadow factory". Stonehouse History Group Journal. 1: 35–38.

- ^ Moore, J.S. (1993). "'Jack Fisher's 'flu, a visitation revisited'". Econ Hist Rev. 2nd series. XLVI: 280–307.

- ^ Hudson, Janet (February 1998). "Residence and Kinship in a Clothing Community: Stonehouse 1558-1804". University of Bristol, Thesis: 87–88.

- ^ Grace. "Stanley Mills, Stroud". Grace's Guide To British Industrial History.

- ^ http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10032570/theme/HOUS

- ^ GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Leonard Stanley AP/CP through time | Housing Statistics | Total Houses, A Vision of Britain through Time.

- ^ "The Stanleys ward 2011". Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Hill, Peter (2014). "Stanley Spencer in Leonard Stanley" (PDF). Stonehouse History Group. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ holmesacourt.org, p. 292.

External links edit

Media related to Leonard Stanley at Wikimedia Commons

- Leonard Stanley at British History Online

- Parish Council website

- Stroud Voices (Leonard Stanley filter) - oral history site