Summary

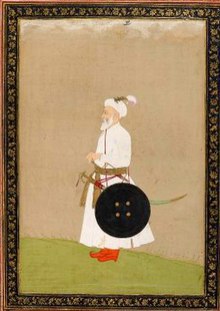

Mian Muhammad Amin Khan Turani (died 28 January 1721),[1] was a Mughal noble of Central Asian origin. He served as sadr-us-sudur (head of religious endowments) during the reign of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, and briefly occupied the post of wazir (prime minister) during the reign of Muhammad Shah. He was the uncle of Chin Qilich Khan, the first Nizam of Hyderabad.

Chin Muhammad Khan Muhammad Amin Khan | |

|---|---|

Amīn Khān | |

| Sadr-us-Sudur of the Mughal Empire | |

| In office 1698–? | |

| Monarch | Aurangzeb |

| Vazīr-i-Āzam of the Mughal Empire | |

| In office 1720–1721 | |

| Monarch | Muhammad Shah |

| Succeeded by | Nizam-ul-Mulk, Asaf Jah I |

| Subahdar of Gujarat | |

| Personal details | |

| Relations | Abid Khan (uncle) Ghaziuddin Khan (cousin) |

| Children | Qamaruddin Khan |

| Parent | Mir Bahauddin |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Mughal Empire |

| Years of service | 1690s-1721 |

| Commands | Mughal Army |

| Battles/wars |

|

Early life edit

Muhammad Amin Khan originated from Samarqand, in the kingdom of Bukhara. His father was Mir Bahauddin, second son of Alam Shaikh, a scholar and descendant of renowned saint Shihabuddin Suhrawardi. Mir Bahauddin served the Khan of Bukhara, and was executed by him around 1686-1687 out of suspicion. Muhammad Amin Khan fled the region and in 1687, arrived in India.[2][3]

Career edit

Upon arrival in India, Muhammad Amin Khan was received by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the Deccan.[2] He was made a Mughal noble through the grant of a mansab, and distinguished himself in several military campaigns, initially serving under his cousin Ghaziuddin Khan. During Aurangzeb's reign, Muhammad Amin Khan belonged to one of the court's two leading factions of nobles.[3] This faction was led by his prominent relatives, namely cousin Ghaziuddin Khan and nephew Chin Qilich Khan.[4] In 1698, Muhammad Amin was appointed sadr-us-sudr of the empire (head of religious endowments) by Aurangzeb. Shortly before Aurangzeb's death, Muhammad Amin was awarded the title of 'Chin Muhammad Khan'.[5]

Following Aurangzeb's death, Muhammad Amin collaborated with Chin Qilich Khan to remain neutral in the ensuing war of succession between the princes. However, disagreeing with Chin Qilich Khan's policy of withdrawal from the court, he maintained a political presence in future years.[6] During the reign of emperor Bahadur Shah, he was one of several nobles dispatched to combat the uprising of the Sikhs led by Banda Singh Bahadur, but failed to succeed; he would then abandon the task of capturing Banda upon Bahadur Shah's death.[7] He later sought the support of the Sayyid brothers to grab power with the ascent of emperor Farrukhsiyar - however, starting in the year 1716, he conspired against them, contributing to their deposition and the coronation of new emperor Muhammad Shah. Under Muhammad Shah, Muhammad Amin Khan was awarded the coveted post of wazir (prime minister), to the dismay of Chin Qilich Khan who had wanted it for himself.[6] However, Muhammad Amin Khan enjoyed only a short tenure of four months before a premature death, following which Chin Qilich Khan received the post of wazir.[8][6] The 1821 travelogue Sair-ul-Manazil mentions Muhammad Amin Khan's tomb being located behind the Ghaziuddin Khan Madrasa in Delhi.[9]

Family edit

Muhammad Amin Khan had several relatives in the Mughal nobility. Muhammad Amin's uncle was Abid Khan, who once held the position of sadr-us-sudr under Aurangzeb. This made Muhammad Amin first cousins with Ghaziuddin Khan, son of Abid Khan and leading noble of Aurangzeb. Muhammad Amin was hence uncle to Ghaziuddin Khan's son Chin Qilich Khan, another prominent noble in the Mughal court (who went on to found the Asaf Jahi dynasty of Hyderabad).[3][5]

Muhammad Amin Khan himself had a son named Qamaruddin Khan, who would also serve as wazir. Muhammad Amin Khan's sister was married to the Mughal governor of Lahore Abd al-Samad Khan, and his daughter was married to the latter's son Zakariya Khan.[10]

References edit

- ^ James Burgess, The Chronology of Modern India, p. 162, Edinburgh, 1913

- ^ a b Irvine, William (1971). Later Mughals. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 263–264.

- ^ a b c Chandra, Satish (2002). Parties and politics at the Mughal Court, 1707-1740 (4th ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 46–49. ISBN 0-19-565444-7. OCLC 50004530.

- ^ Faruqui, Munis Daniyal (2012). Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504-1719. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 297–299. ISBN 978-1-139-52619-7. OCLC 808366461.

- ^ a b Faruqui, Munis D. (2009). "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-Century India". Modern Asian Studies. 43 (1): 12–13 & 8. doi:10.1017/S0026749X07003290. ISSN 1469-8099.

- ^ a b c Faruqui, Munis D. (2009). "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-Century India". Modern Asian Studies. 43 (1): 14–16. doi:10.1017/S0026749X07003290. ISSN 1469-8099.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2002). Parties and politics at the Mughal Court, 1707-1740 (4th ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 90–92. ISBN 0-19-565444-7. OCLC 50004530.

- ^ Raghubir Sinh (1993). Malwa in Transition Or a Century of Anarchy: The First Phase, 1698-1765. Asian Educational Services. p. 142.

- ^ Beg, Mirza Sangin (2018-04-19). "A Description of the Surrounding Environs of Dar-ul Khilafa Shahjahanabad, AND THE INSCRIPTIONS [ON] THE BUILDINGS OF OLD DELHI". Oxford Scholarship Online: 15. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199477739.003.0003.

- ^ Grewal, J. S. (2003). The Sikhs of the Punjab. The new Cambridge history of India / general ed. Gordon Johnson 2, Indian States and the transition to colonialism (Rev. ed., transferred to digital print ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-521-26884-4.