Summary

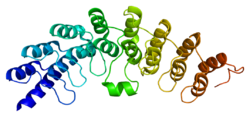

Ribonuclease L or RNase L (for latent), known sometimes as ribonuclease 4 or 2'-5' oligoadenylate synthetase-dependent ribonuclease, is an interferon (IFN)-induced ribonuclease which, upon activation, destroys all RNA within the cell (both cellular and viral). RNase L is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the RNASEL gene.[5]

| RNASEL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | RNASEL, PRCA1, RNS4, ribonuclease L | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 180435 MGI: 1098272 HomoloGene: 8040 GeneCards: RNASEL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This gene encodes a component of the interferon-regulated 2'-5'oligoadenylate (2'-5'A) system that functions in the antiviral and antiproliferative roles of interferons. RNase L is activated by dimerization, which occurs upon 2'-5'A binding, and results in cleavage of all RNA in the cell. This can lead to activation of MDA5, an RNA helicase involved in the production of interferons.

Synthesis and activation edit

RNase L is present in very minute quantities during the normal cell cycle. When interferon binds to cell receptors, it activates transcription of around 300 genes to bring about the antiviral state. Among the enzymes produced is RNase L, which is initially in an inactive form. A set of transcribed genes codes for 2'-5' Oligoadenylate Synthetase (OAS).[6] The transcribed RNA is then spliced and modified in the nucleus before reaching the cytoplasm and being translated into an inactive form of OAS. The location of OAS in the cell and the length of the 2'-5' oligoadenylate depends on the post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications of OAS.[6]

OAS is only activated under a viral infection, when a tight binding of the inactive form of the protein with a viral dsRNA, consisting of the retrovirus' ssRNA and its complementary strand, takes place. Once active, OAS converts ATP to pyrophosphate and 2'-5'-linked oligoadenylates (2-5A), which are 5' end phosphorylated.[7] 2-5 A molecules then bind to RNase L, promoting its activation by dimerization. In its activated form RNase L cleaves all RNA molecules in the cell leading to autophagy and apoptosis. Some of the resulting RNA fragments can also further induce the production of IFN-β as noted in the Significance section.[8]

This dimerization and activation of RNase L can be recognized using Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), as oligoribonucleotides containing a quencher and a fluorophore on opposite sites are added to a solution with inactive RNase L. The FRET signal is then recorded as the quencher and the fluorophore are very close to each other. Upon the addition of 2-5A molecules, RNase L becomes active, cleaving the oligoribonucleotides and interfering in the FRET signal.[9]

Significance edit

RNase L is part of the body's innate immune defense, namely the antiviral state of the cell. When a cell is in the antiviral state, it is highly resistant to viral attacks and is also ready to undergo apoptosis upon successful viral infection. Degradation of all RNA within the cell (which usually occurs with cessation of translation activity caused by protein kinase R) is the cell's last stand against a virus before it attempts apoptosis.

Interferon beta (IFN-β), a type I interferon responsible for antiviral activity, is induced by RNase L and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) in the infected cell. The relationship between RNase L and MDA5 in the production of IFNs has been confirmed with siRNA tests silencing the expression of either molecule and noting a marked decline in IFN production.[11] MDA5, an RNA helicase, is known to be activated by complex high molecular weight dsRNA transcribed from the viral genome.[11][12] In a cell with RNase L, MDA5 activity may be further enhanced.[11] When active, RNase L cleaves and identifies viral RNA and feeds it into MDA5 activation sites, enhancing the production of IFN-β. The RNA fragments produced by RNase L have double stranded regions, as well as specific markers, that allow them to be identified by the RNase L and MDA5.[8] Some studies have suggested that high levels of RNase L may actually inhibit IFN-β production, but a clear linkage still exists between RNase L activity and IFN-β production.[8]

Furthermore, it has been shown that RNase L is involved in many diseases. In 2002, the "hereditary prostate cancer 1" locus (HPC1) was mapped to the RNASEL gene, indicating that mutations in this gene cause a predisposition to prostate cancer.[13][14][15] Impairments of the OAS/RNase L pathway in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) have been investigated.[16][17]

References edit

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000135828 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000066800 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

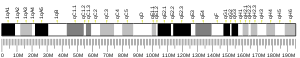

- ^ Squire J, Zhou A, Hassel BA, Nie H, Silverman RH (January 1994). "Localization of the interferon-induced, 2-5A-dependent RNase gene (RNS4) to human chromosome 1q25". Genomics. 19 (1): 174–5. doi:10.1006/geno.1994.1033. PMID 7514564.

- ^ a b Sarkar SN, Pandey M, Sen GC (2005). "Assays for the Interferon-Induced Enzyme 2′,5′ Oligoadenylate Synthetases". Interferon Methods and Protocols. Methods in Molecular Medicine. Vol. 116. Human Press Inc. pp. 81–101. doi:10.1385/1-59259-939-7:081. ISBN 978-1-58829-418-0. PMID 16000856.

- ^ Liang SL, Quirk D, Zhou A (September 2006). "RNase L: its biological roles and regulation". IUBMB Life. 58 (9): 508–14. doi:10.1080/15216540600838232. PMID 17002978.

- ^ a b c Banerjee S, Chakrabarti A, Jha BK, Weiss SR, Silverman RH (February 2014). "Cell-type-specific effects of RNase L on viral induction of beta interferon". mBio. 5 (2): e00856-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.00856-14. PMC 3940032. PMID 24570368.

- ^ Thakur CS, Xu Z, Wang Z, Novince Z, Silverman RH (2005). "A Convenient and Sensitive Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Assay for RNase L and 2′,5′ Oligoadenylates". Interferon Methods and Protocols. Methods in Molecular Medicine. Vol. 116. Human Press Inc. pp. 103–13. doi:10.1385/1-59259-939-7:103. ISBN 978-1-58829-418-0. PMID 16000857.

- ^ Gupta A, Rath PC (2014). "Curcumin, a natural antioxidant, acts as a noncompetitive inhibitor of human RNase L in presence of its cofactor 2-5A in vitro". BioMed Research International. 2014: 817024. doi:10.1155/2014/817024. PMC 4165196. PMID 25254215.

- ^ a b c Luthra P, Sun D, Silverman RH, He B (February 2011). "Activation of IFN-β expression by a viral mRNA through RNase L and MDA5". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (5): 2118–23. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.2118L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012409108. PMC 3033319. PMID 21245317.

- ^ Pichlmair A, Schulz O, Tan CP, Rehwinkel J, Kato H, Takeuchi O, et al. (October 2009). "Activation of MDA5 requires higher-order RNA structures generated during virus infection". Journal of Virology. 83 (20): 10761–9. doi:10.1128/JVI.00770-09. PMC 2753146. PMID 19656871.

- ^ Smith JR, Freije D, Carpten J, Gronberg H, Xu J, Isaacs S, et al. (Nov 1996). "Major susceptibility locus for prostate cancer on chromosome 1 suggested by a genome-wide search". Science. 274 (5291): 1371–4. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1371S. doi:10.1126/science.274.5291.1371. PMID 8910276. S2CID 42684655.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: RNASEL ribonuclease L (2',5'-oligoisoadenylate synthetase-dependent)".

- ^ Carpten J, Nupponen N, Isaacs S, Sood R, Robbins C, Xu J, et al. (February 2002). "Germline mutations in the ribonuclease L gene in families showing linkage with HPC1". Nature Genetics. 30 (2): 181–4. doi:10.1038/ng823. PMID 11799394. S2CID 2922306.

- ^ Nijs J, De Meirleir K (Nov–Dec 2005). "Impairments of the 2-5A synthetase/RNase L pathway in chronic fatigue syndrome". In Vivo. 19 (6): 1013–21. PMID 16277015.

- ^ Suhadolnik RJ, Peterson DL, O'Brien K, Cheney PR, Herst CV, Reichenbach NL, et al. (July 1997). "Biochemical evidence for a novel low molecular weight 2-5A-dependent RNase L in chronic fatigue syndrome". Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 17 (7): 377–85. doi:10.1089/jir.1997.17.377. PMID 9243369.

Further reading edit

- Urisman A, Molinaro RJ, Fischer N, Plummer SJ, Casey G, Klein EA, et al. (March 2006). "Identification of a novel Gammaretrovirus in prostate tumors of patients homozygous for R462Q RNASEL variant". PLOS Pathogens. 2 (3): e25. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020025. PMC 1434790. PMID 16609730.

- Chakrabarti A, Jha BK, Silverman RH (January 2011). "New insights into the role of RNase L in innate immunity". Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 31 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1089/jir.2010.0120. PMC 3021357. PMID 21190483.

- Castelli J, Wood KA, Youle RJ (1999). "The 2-5A system in viral infection and apoptosis". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 52 (9): 386–90. doi:10.1016/S0753-3322(99)80006-7. PMID 9856285.

- Leaman DW, Cramer H (July 1999). "Controlling gene expression with 2-5A antisense". Methods. 18 (3): 252–65. doi:10.1006/meth.1999.0782. PMID 10454983.

- Silverman RH (February 2003). "Implications for RNase L in prostate cancer biology". Biochemistry. 42 (7): 1805–12. doi:10.1021/bi027147i. PMID 12590567.

- Kieffer N, Schmitz M, Scheiden R, Nathan M, Faber JC (2006). "Involvement of the RNAse L gene in prostate cancer". Bulletin de la Société des Sciences Médicales du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (1): 21–8. PMID 16869093.

- Bisbal C, Silverman RH (2007). "Diverse functions of RNase L and implications in pathology". Biochimie. 89 (6–7): 789–98. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2007.02.006. PMC 2706398. PMID 17400356.

- Carter BS, Beaty TH, Steinberg GD, Childs B, Walsh PC (April 1992). "Mendelian inheritance of familial prostate cancer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (8): 3367–71. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.3367C. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.8.3367. PMC 48868. PMID 1565627.

- Dong B, Xu L, Zhou A, Hassel BA, Lee X, Torrence PF, Silverman RH (May 1994). "Intrinsic molecular activities of the interferon-induced 2-5A-dependent RNase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (19): 14153–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)36767-4. PMID 7514601.

- Bisbal C, Martinand C, Silhol M, Lebleu B, Salehzada T (June 1995). "Cloning and characterization of a RNAse L inhibitor. A new component of the interferon-regulated 2-5A pathway". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (22): 13308–17. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.22.13308. PMID 7539425.

- Zhou A, Hassel BA, Silverman RH (March 1993). "Expression cloning of 2-5A-dependent RNAase: a uniquely regulated mediator of interferon action". Cell. 72 (5): 753–65. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90403-D. PMID 7680958.

- Hassel BA, Zhou A, Sotomayor C, Maran A, Silverman RH (August 1993). "A dominant negative mutant of 2-5A-dependent RNase suppresses antiproliferative and antiviral effects of interferon". The EMBO Journal. 12 (8): 3297–304. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05999.x. PMC 413597. PMID 7688298.

- Smith JR, Freije D, Carpten JD, Grönberg H, Xu J, Isaacs SD, et al. (November 1996). "Major susceptibility locus for prostate cancer on chromosome 1 suggested by a genome-wide search". Science. 274 (5291): 1371–4. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1371S. doi:10.1126/science.274.5291.1371. PMID 8910276. S2CID 42684655.

- Egesten A, Dyer KD, Batten D, Domachowske JB, Rosenberg HF (October 1997). "Ribonucleases and host defense: identification, localization and gene expression in adherent monocytes in vitro". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1358 (3): 255–60. doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(97)00081-5. PMID 9366257.

- Eeles RA, Durocher F, Edwards S, Teare D, Badzioch M, Hamoudi R, et al. (March 1998). "Linkage analysis of chromosome 1q markers in 136 prostate cancer families. The Cancer Research Campaign/British Prostate Group U.K. Familial Prostate Cancer Study Collaborators". American Journal of Human Genetics. 62 (3): 653–8. doi:10.1086/301745. PMC 1376940. PMID 9497242.

- Dong B, Silverman RH (January 1999). "Alternative function of a protein kinase homology domain in 2', 5'-oligoadenylate dependent RNase L". Nucleic Acids Research. 27 (2): 439–45. doi:10.1093/nar/27.2.439. PMC 148198. PMID 9862963.

- Carpten JD, Makalowska I, Robbins CM, Scott N, Sood R, Connors TD, et al. (February 2000). "A 6-Mb high-resolution physical and transcription map encompassing the hereditary prostate cancer 1 (HPC1) region". Genomics. 64 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1006/geno.1999.6051. PMID 10708513.

- Zhou A, Nie H, Silverman RH (November 2000). "Analysis and origins of the human and mouse RNase L genes: mediators of interferon action". Mammalian Genome. 11 (11): 989–92. doi:10.1007/s003350010194. PMID 11063255. S2CID 35650613.

- Dong B, Niwa M, Walter P, Silverman RH (March 2001). "Basis for regulated RNA cleavage by functional analysis of RNase L and Ire1p". RNA. 7 (3): 361–73. doi:10.1017/S1355838201002230. PMC 1370093. PMID 11333017.

External links edit

- ribonuclease+L,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)