Summary

USS Santa Olivia (SP-3125) was a cargo ship and later troop transport that served with the United States Navy during and after World War I. The ship later went into merchant service as a freighter, and during World War II took part in a number of transatlantic convoys.

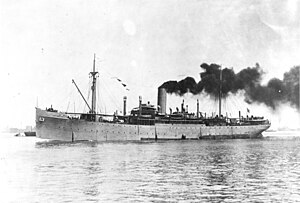

USS Santa Olivia (SP-3125), location unknown, 1919

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Santa Olivia (SP-3125) |

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Builder | William Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia |

| Yard number | 444 |

| Launched | 12 January 1918 |

| Completed | May 1918 |

| Acquired | May 1918 |

| Commissioned | (USN): 1 Jul 1918 – 21 Jul 1919 |

| Maiden voyage | 16 Feb 1918 |

| In service | 16 Feb 1918 – 1950s |

| Renamed |

|

| Fate | Scrapped, La Spezia, Italy, 30 December 1954 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Freighter |

| Tonnage | 6,422 GRT, 3,877 NRT |

| Length | 420 ft 6 ins |

| Beam | 53 ft 7 ins |

| Draft | 28 ft 4 ins |

| Depth of hold | 34 ft 2 ins |

| Decks | 3 |

| Installed power | 1 × 3,000 IHP, 4-cyl. quadruple expansion |

| Propulsion | Single screw |

| Speed | 12 knots |

| Complement |

|

| Armament | 1 × 6 inch; 1 × 6-pdr |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Troop transport |

| Displacement | 13,340 long tons |

| Troops | 32 officers, 1,825 enlisted |

| Complement | 21 officers, 168 enlisted |

| Notes | Other characteristics similar or identical to freighter |

Built in 1918, Santa Olivia was acquired by the Navy on completion, and during the war made two voyages to France as a cargo ship. After the war, she was converted into a troop transport, and repatriated almost 7,500 U.S. troops in four round trips in 1919. A teenage Humphrey Bogart served aboard Santa Olivia in this period.

Decommissioned from the Navy, Santa Olivia entered merchant service for W. R. Grace & Co. in late 1919 as the freighter SS Santa Olivia, operating between the United States and South America. In 1922, the vessel was transferred to the Pacific Mail Steamship Company and used in United States intercoastal service. In 1925, Santa Olivia was sold to the American Hawaiian Steamship Company. Renamed SS Kansan, the ship remained in intercoastal service into the 1930s. During World War II, Kansan transported aircraft, explosives and other vital supplies in convoy to the United Kingdom during the Battle of the Atlantic.

After the war, Kansan was sold to a Panamanian company and renamed SS Jackstar. Jackstar survived bombardment by Arab forces while unloading cargoes at Tel Aviv, Israel during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The ship was sold for scrap in 1954.

Construction and design edit

Santa Olivia—a steel hulled, screw-propelled cargo ship—was built in 1918 by William Cramp & Sons of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for the Atlantic & Pacific Steamship Company, a subsidiary of W. R. Grace & Co.[1] Launched 12 January 1918,[2] Santa Olivia was one of a record 44 ships delivered by U.S. yards in May of the same year.[3]

Santa Olivia was 404.5 feet (123.3 m) in length, with a beam of 53 feet 7 inches (16.33 m), hold depth of 34 feet 2 inches (10.41 m) and draft of 28 feet 4 inches (8.64 m). She had a gross register tonnage of 6,422 and net register tonnage of 3,877. She had three decks, six waterproof bulkheads, two masts and a single smokestack, and was fitted with water ballast tanks.[4]

Santa Olivia was powered by a 3,000 ihp quadruple expansion steam engine with cylinders of 25.5, 37, 52.5 and 76 inches (65, 94, 133 and 193 cm) by 54-inch (140 cm) stroke, driving a single screw propeller. Steam was supplied by three oil-fired Scotch boilers at an operating pressure of 220 pounds.[4] The ship had a speed of 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h).[1][5]

Service history edit

edit

On 1 July 1918, Santa Olivia was acquired by the Navy and commissioned at Philadelphia as USS Santa Olivia (SP-3125).[1]

Santa Olivia was assigned to the Naval Overseas Transportation Service (NOTS) upon commissioning. Departing from Philadelphia on 15 July 1918 for New York, the ship made two round-trip voyages to Europe before the war's end on 11 November 1918. Sailing from New York each time, she carried a total of 10,773 tons of general cargo to Marseilles.[1]

With the war over, the foreign contingent of the American Cruiser and Transport Force withdrew, obliging the U.S. Navy to undertake a rapid expansion of its fleet of troop transports in order to quickly repatriate U.S. forces from France. A total of 56 ships were selected for conversion to troopships,[6] including Santa Olivia. Santa Olivia was detached from NOTS on 20 December 1918[1] and recommissioned as a troop transport the same day.[7] Between 26 December 1918 and 14 February 1919, Santa Olivia was converted to a troop transport by the W. & A. Fletcher Company of Hoboken, New Jersey, at a cost of $150,778.[7] After conversion, the ship had a troop capacity of 32 officers and 1,825 enlisted men,[7] and a crew complement of 21 officers and 168 enlisted men.[5]

Reassigned to the Cruiser and Transport Force, Atlantic Fleet, Santa Olivia embarked on the first of four troop transport missions between the U.S. and France[1] on 16 February 1919, departing New York for Brest,[8] the return voyage being made from 18 to 30 March.[9] Her second such voyage to France returned to Philadelphia on 12 May, with 30 officers and 1,825 men of the 110th Infantry Regiment and three officers of the 178th Machinegun Detachment. The 110th Infantry was described as "the hardest hit of the National Guard regiments", having lost 500 killed and 3,000 wounded in the war.[10] Returning to France, Santa Olivia sailed from Bordeaux on May 30 with 1,891 troops, including 16 officers and 429 men of C and D companies, 303rd Engineers, 78th Division, arriving New York 10 June.[11]

Santa Olivia's final round trip to France for the navy began with a departure from New York on 15 June.[12] At Bordeaux, Santa Olivia embarked another 45 officers and 1,814 men, returning them to New York on 9 July. During this voyage, the ship experienced some rough weather causing a planned onboard Fourth of July celebration to be postponed until the 6th, while two soldiers and one sailor were confined after showing "signs of insanity"; the three men were later transferred to a military hospital for observation.[13] Santa Olivia was the last U.S. troopship to depart from Bordeaux, the port subsequently being abandoned as a U.S Navy embarkation point in favor of Brest.[13] In her four troop repatriation missions, Santa Olivia returned a total of 7,491 officers and men to the United States, including 14 sick or wounded.[14] On 21 July, Santa Olivia was decommissioned at the Grace Line Pier, Brooklyn, and returned the same day to her owner, W. R. Grace & Co.[1]

A teenage Humphrey Bogart served on USS Santa Olivia in 1919 as a coxswain. After being transferred from USS Leviathan (SP-1326) in February, Bogart missed an April sailing of Santa Olivia, but avoided being listed as a deserter by reporting for duty within hours. He was given three days' solitary confinement on bread and water for going AWOL, but the incident did not affect his service record. After returning to the ship, he was honorably discharged on 18 June 1919 with high marks for proficiency and sobriety.[15]

Santa Olivia's commander during her naval service, George H. Miles, would later run afoul of the law. In 1922, while captain of SS President Van Buren, Miles was charged with murder for beating a deranged pantryman, who died the following day. Convicted of "inhumane treatment",[16] Miles was sentenced to 18 months' jail over the incident and lost his masters' licence.[16][17][18] In February 1923, while out on bail pending an appeal of his conviction, Miles was arrested for alleged bootlegging.[16] In 1930, Miles was again arrested by police, for attempted burglary.[18]

Merchant service edit

1920s–1930s edit

After her naval decommission, Santa Olivia entered merchant service on or before September 1919[19] as a cargo ship for W. R. Grace & Co., under the name SS Santa Olivia. For the next few years, the ship operated between New York and various ports in South America, including Rio de Janeiro, Brazil;[19] Valparaiso, Chile;[20] and Callao, Peru.[21] In August 1920, Santa Olivia collided with and sank a tug at Callao, with the freighter suffering minor damage.[22] In July–August 1922, Santa Olivia delivered 3,500 tons of grain to Reval (modern day Tallinn), Estonia, as part of a relief mission to famine-stricken regions of Russia.[23][24]

In October 1922, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, a subsidiary of W. R. Grace, announced the formation of a new freight-and-passenger service to run between the East and West coasts of the United States. The service, which operated on a ten-day schedule, was provided by a fleet of seven ships including Santa Olivia.[25] Ports of call eventually added to the service on the West Coast included Tacoma, Washington and Oakland and San Francisco, California, while those on the East Coast included New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore and Norfolk, Virginia.[26]

Santa Olivia was to remain in intercoastal service with Pacific Mail for some 2 1/2 years. During this time, her cargoes outbound from New York were miscellaneous; on a November 1922 passage to San Francisco, for example, the ship carried cement, rope, ink, lime juice, dates, canned corn and drugs.[24] Return cargoes included copper and lumber.[27][28] Due to falling demand, Pacific Mail reduced its intercoastal schedule in October 1924 from one sailing every ten days to one every two weeks.[29]

On 11 June 1925, W. R. Grace & Co. sold the six freighters of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, including Santa Olivia, to the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company. Pacific Mail's other ships were sold to the Dollar Line, and the former's remaining assets purchased by Grace.[30] The deal brought to a formal end the existence of Pacific Mail, one of America's oldest and best known steamship lines, established in 1848.[31] Acquisition of the Pacific Mail freighters allowed American-Hawaiian to expand its intercoastal service, and Santa Olivia was thus retained on her existing route; with the change of ownership, however, the ship was renamed SS Kansan.[32][2]

By late 1925, Kansan was shipping auto parts and general goods from the East to the West Coasts.[33][34][35] Return cargoes included dried fruit and canned goods.[36][37][38] On 25 June 1926, Kansan grounded on a mudbank at Oakland, but was hauled off with no apparent damage by a tug.[39]

By 1930, the ship was engaged in the transport of cotton and wool from New York to European ports such as Bremen, Germany and Liverpool, England.[40] In July 1938, Kansan was engaged in a mercy dash to San Diego after one of her crew was taken sick; during this trip, the ship recorded a speed in one 24-hour period of 14.21 knots (16.35 mph; 26.32 km/h), completing the passage from Guatemala in 9 days 54 minutes, just short of the record.[41]

World War II edit

During World War II, Kansan remained under the ownership of American-Hawaiian.[2] After America's entry into the war in December 1941, Kansan joined the convoy system, making several transatlantic trips from the U.S. to Great Britain during the Battle of the Atlantic.[42]

Kansan's movements in the early part of the war are uncertain, but the ship is known to have voyaged from Hampton Roads, Virginia to Trinidad in mid-1942. On 14 March 1943, Kansan departed New York for various destinations including Bandar Abbas, Iran, and Bombay, India, before returning to New York 9 October; her cargoes in this period are not known.[42]

On 13 November 1943, Kansan departed New York with a cargo of explosives and general goods bound for Liverpool, England, with convoy HX266, arriving Liverpool on the 27th. Returning to New York with convoy ON215 on 28 December, Kansan departed New York for Liverpool a second time on 22 January 1944 with convoy HX276, this time with a cargo of general goods and aircraft, arriving 7 February. After returning to New York with convoy ON226 between 29 February and 15 March, Kansan travelled to Boston, Massachusetts and Halifax, Nova Scotia, to pick up general cargoes bound for England before returning to New York 11 April. Kansan departed for her third and final wartime transatlantic crossing from New York to Liverpool with convoy HX287 on 14 April, arriving on the 26th.[42]

After returning to New York with ON236 from 12 to 27 May, Kansan relocated over the next few weeks from New York to Guantanamo, Cuba, and Cristobal, Panama.[42] Her subsequent wartime movements are not known.

Postwar service edit

In 1946, Kansan was sold to the Star Line of Panama and renamed SS Jackstar.[43]

On 12 July 1948, Jackstar arrived off Tel Aviv in the fledgling state of Israel during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Jackstar spent the next six days unloading her cargo of flour in spite of intermittent bombardment by Arab forces. Jackstar was undamaged during the operation. The ship made a second voyage to Israel, from New York to Haifa, with eight passengers and general cargoes in February 1950.[44][45]

Jackstar was scrapped at La Spezia, Italy, In December 1954.[2]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g "Santa Olivia". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships online edition. Naval History and Heritage Command website.

- ^ a b c d "Single Ship Report for "2216438"". Miramar Ship Index.

- ^ "44 Ships Delivered to Our Yards in May" (PDF). The New York Times. 1918-06-05.

- ^ a b American Bureau of Shipping 1919. p. 645.

- ^ a b United States Department of Commerce 1920. p. 492.

- ^ United States Department of War 1920. pp. 4974-75.

- ^ a b c United States Department of War 1920. p. 4978.

- ^ "Outging Steamships" (PDF). The New York Times. 1919-02-14.

- ^ "Incoming Steamships" (PDF). The New York Times. 1919-03-30.

- ^ "16 Return Out Of 1,000" (PDF). The New York Times. 1919-05-13.

- ^ "The Santa Olivia in". Altoona Tribune. 1919-06-11. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Outgoing Steamships". New York Tribune. 1919-06-14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Hero of Explosion On Dynamite Ship Home With Medal". New York Tribune. 1919-07-10. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Gleaves 1921. pp. 260-61.

- ^ Meyers 1997. Chapter 1.

- ^ a b c "Seize 6 Autos, Boat, Liquor and 24 Men" (PDF). The New York Times. 1923-10-23. (subscription required)

- ^ "Ship Captain Held For Murder At Sea" (PDF). The New York Times. 1922-08-17.

- ^ a b "G. H. Miles, Captain of Ships at War, Held" (PDF). The New York Times. 1930-08-18. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Foreign Ports". New York Tribune. 1919-10-01. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cable reports". The Sun and New York Herald. 1920-08-11. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Marine intelligence". The Gazette Times. Pittsburgh, PA. 1921-06-30. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Shipping News". The Sun and New York Herald. 1920-09-02. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jerry Scanlon (1922-08-03). "$20,000,000 Russian Relief From U.S. Lies on Reval Wharves". San Francisco Chronicle. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Shipping Notes". San Francisco Chronicle. 1922-11-25. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "10-Day Service to East Coast is Inaugurated". Oakland Tribune. 1922-10-10. p. 29 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Santa Olivia's Ports of Call are Announced". Oakland Tribune. 1924-05-27. p. 32 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coastwise news". Oakland Tribune. 1923-03-27. p. 34 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Business looks good this week". Oakland Tribune. 1922-12-04. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Failing Cargo Cuts Schedule". Oakland Tribune. 1924-10-03. p. 36 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Three Ship Line Deals Stir Port". Oakland Tribune. 1925-06-11. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pacific Mail Ship Sale is Announced". Santa Ana Register. 1925-06-11. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cocoanut Meal Brought Here From Manila". Oakland Tribune. 1925-10-16. p. 43 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Arizonan loads return cargo at Oakland docks". Oakland Tribune. 1925-10-22. p. 26 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Munindes Puts Rush Job Onto Dock Workers". Oakland Tribune. 1926-04-01. p. 30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Copra And Sulphur". Oakland Tribune. 1929-08-01. p. 38 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Freighter Loads 2000 Tons Here For East Coast". Oakland Tribune. 1926-01-22. p. 42 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "First-time caller is due at Howard's". Oakland Tribune. 1927-08-31. p. 23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New rate war threatened as Lines break up". Oakland Tribune. 1931-08-08. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Grounded Freighter Released by Tug". Oakland Tribune. 1926-06-25. p. 35 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Much Cotton to Move". Oakland Tribune. 1930-04-17. p. 39 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sailor Hurried To Medical Care". The Capital Journal. Salem, OR. 1938-07-19. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "Ship search". Arnold Hague Ports Database. Don Kindell. (Enter "Kansan" (without quotes) in ship search field for an interactive list of convoys which included the ship.)

- ^ "Search results for "2216438"". Miramar Ship Index.

- ^ "Ship Sails for Israel" (PDF). The New York Times. 1950-02-06. (subscription required)

- ^ "New Shipping Line Begins Operations". The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle. Milwaukee, WI. 1950-02-10 – via Newspapers.com.

Bibliography edit

Books

- American Bureau of Shipping (1919). 1919 Record of American and Foreign Shipping. New York: American Bureau of Shipping. p. 645.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1997). "Chapter 1". Bogart: A Life in Hollywood. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0395773994. Extract via The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- Gleaves, Albert (1921). A History of the Transport Service. New York: George H. Doran Company. pp. 260-61.

- United States Department of Commerce (1920). Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States For the Year Ended June 30 1919. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 492.

- United States Department of War (1920). War Department Annual Reports, 1919. Vol. I (Part 4). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 4974-78.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

Newspapers

- The New York Times

- Altoona Tribune

- New York Tribune

- The Gazette Times (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania)

- The Sun and New York Herald

- San Francisco Chronicle

- Oakland Tribune

- Santa Ana Register

- The Capital Journal) (Salem, Oregon)

- The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle

Websites

- Arnold Hague Ports Database

- Miramar Ship Index

- Naval History and Heritage Command