Summary

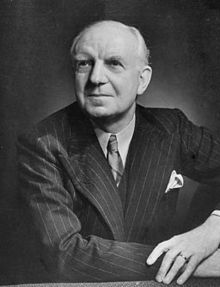

Frederick James Marquis, 1st Earl of Woolton, CH, PC (23 August 1883 – 14 December 1964), was an English businessman and politician who served as chairman of the Conservative Party from 1946 to 1955.

The Earl of Woolton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Materials | |

| In office 1 September 1953 – 16 August 1954 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Arthur Salter |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

| In office 24 November 1952 – 20 December 1955 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill Anthony Eden |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Swinton |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Selkirk |

| Lord President of the Council | |

| In office 28 October 1951 – 24 November 1952 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Addison |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| In office 28 May 1945 – 27 July 1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Clement Attlee |

| Succeeded by | Herbert Morrison |

| Chairman of the Conservative Party | |

| In office 1 July 1946 – 1 November 1955 | |

| Leader | Winston Churchill Anthony Eden |

| Preceded by | Ralph Assheton |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Poole |

| Minister of Reconstruction | |

| In office 11 November 1943 – 23 May 1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Minister of Food | |

| In office 3 April 1940 – 11 November 1943 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | William Morrison |

| Succeeded by | John Llewellin |

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| Hereditary peerage 7 July 1939 – 14 December 1964 | |

| Succeeded by | The 2nd Earl of Woolton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Frederick James Marquis 23 August 1883 Ordsall, Salford, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 14 December 1964 (aged 81) Arundel, Sussex, England |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse(s) |

Maud Smith

(m. 1912; died 1961)Margaret Thomas (m. 1962) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Victoria University of Manchester |

| Occupation | Businessman, politician |

In April 1940, he was appointed Minister of Food and established the rationing system. During this time, he maintained food imports from America and organised a programme of free school meals. The vegetarian Woolton pie was named after Woolton, as one of the recipes commended to the British public due to a shortage of meat, fish, and dairy products during the Second World War. In 1943, Woolton was appointed Minister of Reconstruction, planning for post-war Britain.

Early career edit

Lord Woolton was born at 163 West Park Street in Ordsall, Salford, Lancashire, in 1883. He was the only surviving child of a saddler, Thomas Robert Marquis (1857–1944), and his wife, Margaret Marquis, née Ormerod (1854–1923). Educated in Ardwick and then at Manchester Grammar School and the University of Manchester, Woolton was an active member of the Unitarian Church. He was active in social work in Liverpool (1906–1918).[1]

Woolton hoped to pursue an academic career in the social sciences, but his wish was frustrated by his family's financial circumstances, and he became a mathematics teacher at Burnley Grammar School. He was forced to turn down a research fellowship in Sociology at the University of London but was appointed a research fellow in Economics at the University of Manchester in 1910, where he took the degree of MA in 1912.[1]

Having been judged unfit for military service, Woolton became a civil servant, first in the War Office, then at the Leather Control Board, where he served as a civilian boot controller. At the end of the war, he became secretary of the Boot Manufacturers' Federation, joining Lewis's department store in Liverpool, where he was an executive (1928–1951), becoming director in 1928 and chairman in 1936.[1] In 1938, he responded to the Anschluss by announcing that his stores would boycott Nazi German goods. Despite public support, he was reprimanded by Horace Wilson on behalf of Neville Chamberlain's National Government for diverging from its European policy of appeasement.[2]

Woolton was knighted in 1935 and was raised to the peerage in 1939 for his contribution to British industry. Despite his wishes, he was informed that it was not possible to be Baron Marquis (because "Marquess", or "Marquis", is another grade of the peerage of the United Kingdom), so he took the title Baron Woolton after the Liverpool suburb of Woolton in which he had lived. He subsequently served on several government committees (including the Cadman committee). He refused to affiliate himself with any political party.[1]

Second World War edit

In April 1940, Woolton was appointed as Minister of Food by Neville Chamberlain, one of several ministerial appointments from outside politics. Woolton retained this position until 1943. He supervised 50,000 employees and over a thousand local offices where people could obtain ration cards. His ministry had a virtual monopoly of all food sold in Britain, whether imported or local. His mission was to guarantee adequate nutrition for everyone. With food supplies cut sharply because of enemy action and the needs of the services, rationing was essential. Woolton and his advisors had one scheme in mind, but economists convinced them to instead try point rationing.[1] Everyone would have a certain number of points a month that they could allocate any way they wanted. The experimental approach to food rationing has been considered successful; indeed, food rationing was a major success story in Britain's war.[3]

In late June 1940, with a German invasion threatened, Woolton reassured the public that emergency food stocks were in place that would last "for weeks and weeks" even if the shipping could not get through. He said "iron rations" were stored for use only in great emergency. Other rations were stored in the outskirts of cities liable to German bombing.[4] When the Blitz began in late summer 1940, he was ready with more than 200 feeding stations in London and other cities under attack.[5]

Woolton had the task of overseeing rationing due to wartime shortages. He took the view that it was insufficient to merely impose restrictions but that a programme of advertising to support it was also required. He warned that meat and cheese, as well as bacon and eggs, were in very short supply and would remain that way. Calling for a simpler diet, he noted that there was plenty of bread, potatoes, vegetable oils, fats, and milk.[6]

By January 1941, the usual overseas food supply had fallen in half. By 1942, however, ample food supplies were arriving through Lend Lease from the U.S. and a similar Canadian programme. Worried about children, he made sure that by 1942 Britain was providing 650,000 children with free school meals; about 3,500,000 children received milk at school, in addition to priority supplies at home. However, his national loaf of wholemeal brown bread replaced the ordinary white variety, to the distaste of most housewives.[7] Children learned that sweets supplies were reduced to save shipping space.[8]

Woolton kept food prices down by subsidizing eggs and other items. He promoted recipes that worked well with the rationing system, including the "Woolton pie," which consisted of carrots, parsnips, potatoes, and turnips in oatmeal, with a pastry or potato crust, and served with brown gravy. Woolton's business skills made the Ministry of Food's job a success, and he earned a strong personal popularity despite the shortages.[9][10]

He joined the Privy Council in 1940 and became a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour in 1942. In 1943, Woolton entered the War Cabinet as Minister of Reconstruction, taking charge of the difficult task of planning for post-war Britain and in this role, he appeared on the cover of Time on the issue of 26 March 1945.[11] In May 1945, he featured in Winston Churchill's "Caretaker" government as Lord President of the Council.

President of the Royal Statistical Society edit

In November 1945, Woolton gave his inaugural address as President of the Royal Statistical Society.[12]

Conservative Party manager edit

In July 1945, Churchill lost the 1945 general election, and his government fell. The next day, Woolton joined the Conservative Party and was soon appointed party chairman, with the job of improving the party's organisation in the country and revitalising it for future elections. Under Woolton, many sweeping reforms were carried out, and when the Conservatives returned to government in 1951, Woolton served in the Cabinet for the next four years.

Woolton rebuilt the local organisations with an emphasis on membership, money, and a unified national propaganda appeal on critical issues. To broaden the base of potential candidates, the national party provided financial aid to candidates and assisted the local organisations in raising local money. Woolton also proposed changing the name of the party to the Union Party and later emphasised a rhetoric that characterised opponents as "Socialist" rather than "Labour".[citation needed] He was given credit for the Conservative victory in 1951, their first since 1935.[13]

In May 1950, Woolton, with Churchill's approval, called for a kind of coalition with the Liberal Party based on nine principles he said they agreed upon:[14]

- Opposition to "the over-encroaching power of the State over the lives of individuals and of the processes which this commercial nation lives"

- Opposition to the nationalisation of the means of production, distribution and exchange, "which is the creed of socialism";

- Opposition to "the centralisation of government in Whitehall and the weakening of the influence of local authorities";

- Belief in "the establishment, under private enterprise, of partnership in industry, whereby all ranks engaged in it shall … share in the increased yield that comes from greater effort or increased skill";

- Belief in the maintenance of a high and stable level of employment,

- Belief that "the best purposes of the State are served when there is economy in public administration and when Government conducted with rigorous avoidance of waste";

- Belief in high standards of health, housing, and education, coupled with religious freedom;

- Recognition of the national duty of maintaining sufficient defense forces, of the danger of militant Communism, and of the necessity for close economic and political cooperation with America and Western Europe;

- "Tolerance, comradeship and unity among all classes."

The Liberal leadership rejected the coalition as one that the Conservatives would control. Labour had recently narrowly won the 1950 general election. The Conservatives without Liberal help won the 1951 general election.

In the 1953 Coronation Honours, he became Viscount Woolton.[15][16]

In 1956, he was further honoured when he became Earl of Woolton with the subsidiary title Viscount Walberton.[17]

Death edit

Woolton died 14 December 1964 at his home, Walberton House, in Arundel, Sussex. His titles passed to his son, Roger. He is buried at St Mary's Church, Walberton, Sussex.[18]

Arms edit

|

References edit

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Kandiah, Michael D. (2004). "Marquis, Frederick James, first earl of Woolton (1883–1964), politician and businessman". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34885. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 22 October 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Bouverie, Tim (2019). Appeasement: Chamberlain, Hitler, Churchill, and the Road to War (1 ed.). New York: Tim Duggan Books. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-451-49984-4. OCLC 1042099346.

- ^ Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939–45 (1969), pp. 380–87 excerpt and text search

- ^ Keesing's Contemporary Archives Volume III-IV, (June 1940), p. 4117.

- ^ Keesing's Contemporary Archives Volume III-IV, (September 1940), p. 4260.

- ^ Keesing's Contemporary Archives, Volume IV, (February 1941), p. 4474.

- ^ Lacey (1994), pp. 108–109.

- ^ Keesing's Contemporary Archives, Volume IV, (March 1942), p. 5080.

- ^ Longmate (2010), p. 152.

- ^ "Lord Woolton, 81, Food Minister In Early Years of War, Is Dead; Rebuilt British Conservatives in 9 Years as Chairman—Initiated Ration Points". The New York Times. 15 December 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ Sitwell, William (2 June 2016). Eggs or Anarchy: The remarkable story of the man tasked with the impossible: to feed a nation at war. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4711-5108-8.

- ^ Lord Woolton: The man who used statistics (and more) to feed a nation at war. Brian Tarran. First published: 09 June 2017, Significance Magazine, Royal Statistical Society. doi:10.1111/j.1740-9713.2017.01036.x

- ^ Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major (1997), pp. 259–264.

- ^ Keesing's Contemporary Archives, Volume VII-VIII, May 1950, p. 10717.

- ^ "No. 39863". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 June 1953. p. 2940.

- ^ "No. 39904". The London Gazette. 3 July 1953. p. 3677.

- ^ "No. 40682". The London Gazette. 10 January 1956. p. 219.

- ^ Delorme (1987), p. 54.

Bibliography

- Delorme, Mary (1987), Curious Sussex, Robert Hale, ISBN 0-7090-2970-5

- Lacey, Richard W. (1994), Hard to Swallow: A Brief History of Food, Cambridge University Press, p. 108, ISBN 978-0-521-44001-1

- Longmate, Norman (2010). How We Lived Then: A History of Everyday Life During the Second World War. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4090-4643-1.

Further reading edit

- Cowling, Maurice (1975). The Impact of Hitler: British Politics & Policy 1933–1940. Cambridge University Press. p. 419. ISBN 0-521-20582-4.

- Hammond, R. J. Food, Volume 1: The Growth of Policy (London: HMSO, 1951); Food, Volume 2: Studies in Administration and Control (1956); Food, Volume 3: Studies in Administration and Control (1962) official war history

- Hammond, R. J. Food and agriculture in Britain, 1939–45: Aspects of wartime control (Food, agriculture, and World War II) (1954)

- Kandiah, Michael D. (May 2008). "Marquis, Frederick James, first earl of Woolton (1883–1964)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34885. Retrieved 8 August 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Sitwell, William (2016). Eggs or Anarchy? The Remarkable Story of the Man Tasked with the Impossible: To Feed a Nation at War. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4711-5105-7.

Michael Kandiah & Judith Rowbotham (Editors), The Diaries and Letters of Lord Woolton 1940–1945. Records of Social and Economic History Series, vol. 61. Oxford: University Press for the British Academy, 2020. Hardcover. xxvii+324 p. ISBN 978-0-19-726684-7.

External links edit

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Woolton

- Catalogue of the papers of Frederick Marquis, Lord Woolton, at the Bodleian Library, Oxford

- Newspaper clippings about Frederick Marquis, 1st Earl of Woolton in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW