Summary

The Histories (Greek: Ἱστορίαι, Historíai;[a] also known as The History[1]) of Herodotus is considered the founding work of history in Western literature.[2] Although not a fully impartial record, it remains one of the West's most important sources regarding these affairs. Moreover, it established the genre and study of history in the Western world (despite the existence of historical records and chronicles beforehand).

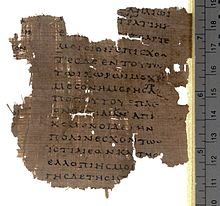

Fragment from Histories, Book VIII on 2nd-century Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 2099 | |

| Author | Herodotus |

|---|---|

| Country | Greece |

| Language | Ancient Greek |

| Genre | History |

| Publisher | Various |

Publication date | c. 430 BC[citation needed] |

The Histories also stands as one of the earliest accounts of the rise of the Persian Empire, as well as the events and causes of the Greco-Persian Wars between the Persian Empire and the Greek city-states in the 5th century BC. Herodotus portrays the conflict as one between the forces of slavery (the Persians) on the one hand, and freedom (the Athenians and the confederacy of Greek city-states which united against the invaders) on the other. The Histories was at some point divided into the nine books that appear in modern editions, conventionally named after the nine Muses.

Motivation for writing edit

Herodotus claims to have traveled extensively around the ancient world, conducting interviews and collecting stories for his book, almost all of which covers territories of the Persian Empire. At the beginning of The Histories, Herodotus sets out his reasons for writing it:

Here are presented the results of the enquiry carried out by Herodotus of Halicarnassus. The purpose is to prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time, and to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by both Greeks and non-Greeks; among the matters covered is, in particular, the cause of the hostilities between Greeks and non-Greeks.

— Herodotus, The Histories, Robin Waterfield translation (2008)

Summary edit

Book I (Clio) edit

- The abductions of Io, Europa, and Medea, which motivated Paris to abduct Helen. The subsequent Trojan War is marked as a precursor to later conflicts between peoples of Asia and Europe. (1.1–5)[3]

- Colchis, Colchians and Medea. (1.2.2–1.2.3)

- The rulers of Lydia (on the west coast of Asia Minor, today modern Turkey): Candaules, Gyges, Ardys, Sadyattes, Alyattes, Croesus (1.6–7)

- How Candaules made his bodyguard, Gyges, view the naked body of his wife. Upon discovery, she ordered Gyges to murder Candaules or face death himself[1]

- How Gyges took the kingdom from Candaules (1.8–13)

- The singer Arion's ride on the dolphin (1.23–24)

- Solon's answer to Croesus's question that Tellus was the happiest person in the world (1.29–33)

- Croesus's efforts to protect his son Atys, his son's accidental death by Adrastus (1.34–44)

- Croesus's test of the oracles (1.46–54)

- The answer from the Oracle of Delphi concerning whether Croesus should attack the Persians (famous for its ambiguity): If you attack, a great empire will fall.

- Peisistratos' rises and falls from power as tyrant of Athens (1.59–64)

- The rise of Sparta (1.65–68)

- A description the geographic location of several Anatolian tribes, including the Cappadocians, Matieni, Phrygians, and Paphlagonians. (1.72)

- The Battle of Halys; Thales predicts the solar eclipse of May 28, 585 BC (1.74)

- Croesus's defeat by Cyrus II of Persia, and how he later became Cyrus's advisor (1.70–92)

- The Tyrrhenians' descent from the Lydians: "Then the one group, having drawn the lot, left the country and came down to Smyrna and built ships, in which they loaded all their goods that could be transported aboard ship, and sailed away to seek a livelihood and a country; until at last, after sojourning with one people after another, they came to the Ombrici, where they founded cities and have lived ever since. They no longer called themselves Lydians, but Tyrrhenians, after the name of the king's son who had led them there,". (1.94)[4]

- The rulers of the Medes: Deioces, Phraortes, Cyaxares, Astyages, Cyrus II of Persia (1.95–144)

- The rise of Deioces over the Medes

- Astyages's attempt to destroy Cyrus, and Cyrus's rise to power

- Harpagus tricked into eating his son, his revenge against Astyages by assisting Cyrus

- The culture of the Persians

- The history and geography of the Ionians, and the attacks on it by Harpagus

- Pactyes' convinces the Lydians to revolt. Rebellion fails and he seeks refuge from Mazares in Cyme (Aeolis)

- The culture of Assyria, especially the design and improvement of the city of Babylon and the ways of its people

- Cyrus's attack on Babylon, including his revenge on the river Gyndes and his famous method for entering the city

- Cyrus's ill-fated attack on the Massagetæ, leading to his death

Book II (Euterpe) edit

- The proof of the antiquity of the Phrygians by the use of children unexposed to language

- The geography, customs, and history of Egypt (Sections 2–182)

- Speculations on the Nile river (Sections 2-34)

- The religious practices of Egypt, especially as they differ from the Greeks (sections 35–64)

- The animals of Egypt: cats, dogs, crocodiles, hippopotamuses, otters, phoenixes, sacred serpents, winged snakes, ibises

- The culture of Egypt: medicine, funeral rites, food, boats[6]

- The kings of Egypt: Menes, Nitocris, Mœris, Sesostris, Pheron, Proteus

- Helen and Paris's stay in Egypt, just before the Trojan War (2.112–120) [7]

- More kings of Egypt: Rhampsinit (and the story of the clever thief), Cheops (and the building of the Great Pyramid of Giza using machines), Chephren, Mycerinus, Asychis and the Ethiopian conqueror Sabacos, Anysis, Sethos

- The line of priests

- The Labyrinth

- More kings of Egypt: the twelve, Psammetichus (and his rise to power), Necôs, Psammis, Apries, Amasis II (and his rise to power)

Book III (Thalia) edit

- Cambyses II of Persia's (son of Cyrus II and king of Persia) attack on Egypt, and the defeat of the Egyptian king Psammetichus III.

- Cambyses's abortive attack on Ethiopia

- The madness of Cambyses

- The good fortune of Polycrates, king of Samos

- Periander, the king of Corinth and Corcyra, and his obstinate son

- The revolt of the two Magi in Persia and the death of Cambyses

- The conspiracy of the seven to remove the Magi

- The rise of Darius I of Persia.

- The twenty satrapies

- The culture of India and their method of collecting gold

- The culture of Arabia and their method of collecting spices

- The flooded valley with five gates

- Orœtes's (governor of Sardis) scheme against Polycrates

- The physician Democêdes

- The rise of Syloson governor of Samos

- The revolt of Babylon and its defeat by the scheme of Zopyrus

Book IV (Melpomene) edit

- The history of the Scythians (from the land north of the Black Sea)

- The miraculous poet Aristeas

- The geography of Scythia

- The inhabitants of regions beyond Scythia: Sauromatae, Budini, Thyssagetae, Argippaeans, Issedones, Arimaspi, Hyperboreans

- A comparison of Libya (Africa), Asia, and Europe

- The rivers of Scythia: the Ister, the Tyras, the Hypanis, the Borysthenes, the Panticapes, the Hypacyris, the Gerrhus, and the Tanais

- The culture of the Scythians: religion, burial rites, xenophobia (the stories of Anacharsis and Scylas), population (sections 59–81)

- The beginning of Darius's attack on Scythia, including the pontoon bridge over the Bosphorus

- The brutal worship of Zalmoxis by the Getae

- The customs of the surrounding peoples: Tauri, Agathyrsi, Neuri, Androphagi (man-eaters), Melanchlaeni, Geloni, Budini, Sauromatae

- The wooing of the Amazons by the Scyths, forming the Sauromatae

- Darius's failed attack on Scythia and consequent retreat

- The story of the Minyæ (descendants of the Argonauts) and the founding of Cyrene

- The kings of Cyrene: Battus I, Arcesilaus I, Battus II, Arcesilaus II, Battus III (and the reforms of Demonax), Arcesilaus III (and his flight, restoration, and assassination), Battus IV, and Arcesilaus IV (his revolt and death)

- The peoples of Libya from east to west

- The revenge of Arcesilaus' mother Pheretima

Book V (Terpsichore) edit

- The attack on the Thracians by Megabazus

- The removal of the Paeonians to Asia

- The slaughter of the Persian envoys by Alexander I of Macedon

- The failed attack on the Naxians by Aristagoras, tyrant of Miletus

- The revolt of Miletus against Persia

- The background of Cleomenes I, king of Sparta, and his half brother Dorieus

- The description of the Persian Royal Road from Sardis to Susa

- The introduction of writing to Greece by the Phoenicians

- The freeing of Athens by Sparta, and its subsequent attacks on Athens

- The reorganizing of the Athenian tribes by Cleisthenes

- The attack on Athens by the Thebans and Eginetans

- The backgrounds of the tyrants of Corinth Cypselus and his son Periander

- Aristagoras's failed request for help from Sparta, and successful attempt with Athens

- The burning of Sardis, and Darius's vow for revenge against the Athenians

- Persia's attempts to quell the Ionian revolt

Book VI (Erato) edit

- The fleeing of Histiaeus to Chios

- The training of the Ionian fleet by Dionysius of Phocaea

- The abandonment of the Ionian fleet by the Samians during battle

- The defeat of the Ionian fleet by the Persians

- The capture and death of Histiaeus by Harpagus

- The invasion of Greek lands under Mardonius and enslavement of Macedon

- The destruction of 300 ships in Mardonius's fleet near Athos

- The order of Darius that the Greeks provide him earth and water, in which most consent, including Aegina

- The Athenian request for assistance of Cleomenes of Sparta in dealing with the traitors

- The history behind Sparta having two kings and their powers

- The dethronement of Demaratus, the other king of Sparta, due to his supposed false lineage

- The arrest of the traitors in Aegina by Cleomenes and the new king Leotychides

- The suicide of Cleomenes in a fit of madness, possibly caused by his war with Argos, drinking unmixed wine, or his involvement in dethroning Demaratus

- The battle between Aegina and Athens

- The taking of Eretria by the Persians after the Eretrians sent away Athenian help

- Pheidippides's encounter with the god Pan on a journey to Sparta to request aid

- The assistance of the Plataeans, and the history behind their alliance with Athens

- The Athenian win at the Battle of Marathon, led by Miltiades and other strategoi (This section starts roughly around 6.100)[8]

- The Spartans late arrival to assist Athens

- The history of the Alcmaeonidae and how they came about their wealth and status

- The death of Miltiades after a failed attack on Paros and the successful taking of Lemnos

Book VII (Polymnia) edit

- The amassing of an army by Darius after learning about the defeat at Marathon (7.1)

- The quarrel between Ariabignes and Xerxes over which son should succeed Darius in which Xerxes is chosen (7.2-3)

- The death of Darius in 486 BC (7.4)

- The defeat of the Egyptian rebels by Xerxes

- The advice given to Xerxes on invading Greece: Mardonius for invasion, Artabanus against (7.9-10)

- The dreams of Xerxes in which a phantom frightens him and Artabanus into choosing invasion

- The preparations for war, including building the Xerxes Canal and Xerxes' Pontoon Bridges across the Hellespont

- The offer by Pythius to give Xerxes all his money, in which Xerxes rewards him

- The request by Pythius to allow one son to stay at home, Xerxes's anger, and the march out between the butchered halves of Pythius's sons

- The destruction and rebuilding of the bridges built by the Egyptians and Phoenicians at Abydos

- The siding with Persia of many Greek states, including Thessaly, Thebes, Melia, and Argos

- The refusal of aid after negotiations by Gelo of Syracuse, and the refusal from Crete

- The destruction of 400 Persian ships due to a storm

- The small Greek force (approx. 7,000) led by Leonidas I, sent to Thermopylae to delay the Persian army (~5,283,220 (Herodotus) )

- The Battle of Thermopylae in which the Greeks hold the pass for 3 days

- The secret pass divulged by Ephialtes of Trachis, which Hydarnes uses to lead forces around the mountains to encircle the Greeks

- The retreat of all but the Spartans, Thespians, and Thebans (forced to stay by the Spartans).

- The Greek defeat and order by Xerxes to remove Leonidas's head and attach his torso to a cross

Book VIII (Urania) edit

- Greek fleet is led by Eurybiades, a Spartan commander who led the Greek fleet after the meeting at the Isthmus 481 BC,

- The destruction by storm of two hundred ships sent to block the Greeks from escaping

- The retreat of the Greek fleet after word of a defeat at Thermopylae

- The supernatural rescue of Delphi from a Persian attack

- The evacuation of Athens assisted by the fleet

- The reinforcement of the Greek fleet at Salamis Island, bringing the total ships to 378

- The destruction of Athens by the Persian land force after difficulties with those who remained

- The Battle of Salamis, the Greeks have the advantage due to better organization, and fewer losses due to ability to swim

- The description of the Angarum, the Persian riding post

- The rise in favor of Artemisia, the Persian woman commander, and her council to Xerxes in favor of returning to Persia

- The vengeance of Hermotimus, Xerxes' chief eunuch, against Panionius

- The attack on Andros by Themistocles, the Athenian fleet commander and most valiant Greek at Salamis

- The escape of Xerxes and leaving behind of 300,000 picked troops under Mardonius in Thessaly

- The ancestry of Alexander I of Macedon, including Perdiccas

- The refusal of an attempt by Alexander to seek a Persian alliance with Athens

Book IX (Calliope) edit

- The second taking of an evacuated Athens

- The evacuation to Thebes by Mardonius after the sending of Lacedaemonian troops

- The slaying of Masistius, leader of the Persian cavalry, by the Athenians

- The warning from Alexander to the Greeks of an impending attack

- The death of Mardonius by Aeimnestus

- The Persian retreat to Thebes where they are afterwards slaughtered (Battle of Plataea)

- The description and dividing of the spoils

- The speedy escape of Artabazus into Asia.

- The Persian defeat in Ionia by the Greek fleet (Battle of Mycale), and the Ionian revolt

- The mutilation of the wife of Masistes ordered by Amestris, wife of Xerxes

- The death of Masistes after his intent to rebel

- The Athenian blockade of Sestos and the capture of Artayctes

- The Persians' abortive suggestion to Cyrus to migrate from rocky Persis

Style edit

In his introduction to Hecataeus' work, Genealogies:

Hecataeus the Milesian speaks thus: I write these things as they seem true to me; for the stories told by the Greeks are various and in my opinion absurd.

This points forward to the "folksy" yet "international" outlook typical of Herodotus. However, one modern scholar has described the work of Hecataeus as "a curious false start to history,"[9] since despite his critical spirit, he failed to liberate history from myth. Herodotus mentions Hecataeus in his Histories, on one occasion mocking him for his naive genealogy and, on another occasion, quoting Athenian complaints against his handling of their national history.[10] It is possible that Herodotus borrowed much material from Hecataeus, as stated by Porphyry in a quote recorded by Eusebius.[11] In particular, it is possible that he copied descriptions of the crocodile, hippopotamus, and phoenix from Hecataeus's Circumnavigation of the Known World (Periegesis / Periodos ges), even misrepresenting the source as "Heliopolitans" (Histories 2.73).[12]

But Hecataeus did not record events that had occurred in living memory, unlike Herodotus, nor did he include the oral traditions of Greek history within the larger framework of oriental history.[13] There is no proof that Herodotus derived the ambitious scope of his own work, with its grand theme of civilizations in conflict, from any predecessor, despite much scholarly speculation about this in modern times.[9][14] Herodotus claims to be better informed than his predecessors by relying on empirical observation to correct their excessive schematism. For example, he argues for continental asymmetry as opposed to the older theory of a perfectly circular earth with Europe and Asia/Africa equal in size (Histories 4.36 and 4.42). However, he retains idealizing tendencies, as in his symmetrical notions of the Danube and Nile.[15]

His debt to previous authors of prose "histories" might be questionable, but there is no doubt that Herodotus owed much to the example and inspiration of poets and story-tellers. For example, Athenian tragic poets provided him with a world-view of a balance between conflicting forces, upset by the hubris of kings, and they provided his narrative with a model of episodic structure. His familiarity with Athenian tragedy is demonstrated in a number of passages echoing Aeschylus's Persae, including the epigrammatic observation that the defeat of the Persian navy at Salamis caused the defeat of the land army (Histories 8.68 ~ Persae 728). The debt may have been repaid by Sophocles because there appear to be echoes of The Histories in his plays, especially a passage in Antigone that resembles Herodotus's account of the death of Intaphernes (Histories 3.119 ~ Antigone 904–920).[16] However, this point is one of the most contentious issues in modern scholarship.[17]

Homer was another inspirational source.[c] Just as Homer drew extensively on a tradition of oral poetry, sung by wandering minstrels, so Herodotus appears to have drawn on an Ionian tradition of story-telling, collecting and interpreting the oral histories he chanced upon in his travels. These oral histories often contained folk-tale motifs and demonstrated a moral, yet they also contained substantial facts relating to geography, anthropology, and history, all compiled by Herodotus in an entertaining style and format.[19]

Mode of explanation edit

Herodotus writes with the purpose of explaining; that is, he discusses the reason for or cause of an event. He lays this out in the preamble: "This is the publication of the research of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, so that the actions of people shall not fade with time, so that the great and admirable achievements of both Greeks and barbarians shall not go unrenowned, and, among other things, to set forth the reasons why they waged war on each other."[20]

This mode of explanation traces itself all the way back to Homer,[21] who opened the Iliad by asking:

- Which of the immortals set these two at each other's throats?

- Zeus' son and Leto's, offended

- by the warlord. Agamemnon had dishonored

- Chryses, Apollo's priest, so the god

- struck the Greek camp with plague,

- and the soldiers were dying of it.[22]

Both Homer and Herodotus begin with a question of causality. In Homer's case, "who set these two at each other's throats?" In Herodotus's case, "Why did the Greeks and barbarians go to war with each other?"

Herodotus's means of explanation does not necessarily posit a simple cause; rather, his explanations cover a host of potential causes and emotions. It is notable, however, that "the obligations of gratitude and revenge are the fundamental human motives for Herodotus, just as ... they are the primary stimulus to the generation of narrative itself."[23]

Some readers of Herodotus believe that his habit of tying events back to personal motives signifies an inability to see broader and more abstract reasons for action. Gould argues to the contrary that this is likely because Herodotus attempts to provide the rational reasons, as understood by his contemporaries, rather than providing more abstract reasons.[24]

Types of causality edit

Herodotus attributes cause to both divine and human agents. These are not perceived as mutually exclusive, but rather mutually interconnected. This is true of Greek thinking in general, at least from Homer onward.[25] Gould notes that invoking the supernatural in order to explain an event does not answer the question "why did this happen?" but rather "why did this happen to me?" By way of example, faulty craftsmanship is the human cause for a house collapsing. However, divine will is the reason that the house collapses at the particular moment when I am inside. It was the will of the gods that the house collapsed while a particular individual was within it, whereas it was the cause of man that the house had a weak structure and was prone to falling.[26]

Some authors, including Geoffrey de Ste-Croix and Mabel Lang, have argued that Fate, or the belief that "this is how it had to be," is Herodotus's ultimate understanding of causality.[27] Herodotus's explanation that an event "was going to happen" maps well on to Aristotelean and Homeric means of expression. The idea of "it was going to happen" reveals a "tragic discovery" associated with fifth-century drama. This tragic discovery can be seen in Homer's Iliad as well.[28]

John Gould argues that Herodotus should be understood as falling in a long line of story-tellers, rather than thinking of his means of explanation as a "philosophy of history" or "simple causality." Thus, according to Gould, Herodotus's means of explanation is a mode of story-telling and narration that has been passed down from generations prior:[29]

Herodotus' sense of what was 'going to happen' is not the language of one who holds a theory of historical necessity, who sees the whole of human experience as constrained by inevitability and without room for human choice or human responsibility, diminished and belittled by forces too large for comprehension or resistance; it is rather the traditional language of a teller of tales whose tale is structured by his awareness of the shape it must have and who presents human experience on the model of the narrative patterns that are built into his stories; the narrative impulse itself, the impulse towards 'closure' and the sense of an ending, is retrojected to become 'explanation'.[30]

Reliability edit

The accuracy of the works of Herodotus has been controversial since his own era. Kenton L. Sparks writes, "In antiquity, Herodotus had acquired the reputation of being unreliable, biased, parsimonious in his praise of heroes, and mendacious". The historian Duris of Samos called Herodotus a "myth-monger".[31] Cicero (On the Laws I.5) said that his works were full of legends or "fables".[32] The controversy was also commented on by Aristotle, Flavius Josephus and Plutarch.[33][34] The Alexandrian grammarian Harpocration wrote a whole book on "the lies of Herodotus".[35] Lucian of Samosata went as far as to deny the "father of history" a place among the famous on the Island of the Blessed in his Verae Historiae.

The works of Thucydides were often given preference for their "truthfulness and reliability",[36] even if Thucydides basically continued on foundations laid by Herodotus, as in his treatment of the Persian Wars.[37] In spite of these lines of criticism, Herodotus' works were in general kept in high esteem and regarded as reliable by many. Many scholars, ancient and modern (such as Strabo, A. H. L. Heeren, etc.), routinely cited Herodotus.

To this day, some scholars regard his works as being at least partly unreliable. Detlev Fehling writes of "a problem recognized by everybody", namely that Herodotus frequently cannot be taken at face value.[38] Fehling argues that Herodotus exaggerated the extent of his travels and invented his sources.[39] For Fehling, the sources of many stories, as reported by Herodotus, do not appear credible in themselves. Persian and Egyptian informants tell stories that dovetail neatly into Greek myths and literature, yet show no signs of knowing their own traditions. For Fehling, the only credible explanation is that Herodotus invented these sources, and that the stories themselves were concocted by Herodotus himself.[40]

Like many ancient historians, Herodotus preferred an element of show[d] to purely analytic history, aiming to give pleasure with "exciting events, great dramas, bizarre exotica."[42] As such, certain passages have been the subject of controversy[43][44] and even some doubt, both in antiquity and today.[45][46][47][48][49][50][51]

Despite the controversy,[52] Herodotus has long served and still serves as the primary, often only, source for events in the Greek world, Persian Empire, and the broader region in the two centuries leading up to his own days.[53][54] So even if the Histories were criticized in some regards since antiquity, modern historians and philosophers generally take a more positive view as to their source and epistemologic value.[55] Herodotus is variously considered "father of comparative anthropology,"[53] "the father of ethnography,"[54] and "more modern than any other ancient historian in his approach to the ideal of total history."[55]

Discoveries made since the end of the 19th century have generally added to Herodotus' credibility. He described Gelonus, located in Scythia, as a city thousands of times larger than Troy; this was widely disbelieved until it was rediscovered in 1975. The archaeological study of the now-submerged ancient Egyptian city of Heracleion and the recovery of the so-called "Naucratis stela" give credibility to Herodotus's previously unsupported claim that Heracleion was founded during the Egyptian New Kingdom.

Babylon edit

Herodotus claimed to have visited Babylon. The absence of any mention of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon in his work has attracted further attacks on his credibility. In response, Dalley has proposed that the Hanging Gardens may have been in Nineveh rather than in Babylon.[49]

Egypt edit

The reliability of Herodotus's writing about Egypt is sometimes questioned.[51] Alan B. Lloyd argues that, as a historical document, the writings of Herodotus are seriously defective, and that he was working from "inadequate sources."[45] Nielsen writes: "Though we cannot entirely rule out the possibility of Herodotus having been in Egypt, it must be said that his narrative bears little witness to it."[47] German historian Detlev Fehling questions whether Herodotus ever traveled up the Nile River, and considers doubtful almost everything that he says about Egypt and Ethiopia.[56][50] Fehling states that "there is not the slightest bit of history behind the whole story" about the claim of Herodotus that Pharaoh Sesostris campaigned in Europe, and that he left a colony in Colchia.[48][46] Fehling concludes that the works of Herodotus are intended as fiction. Boedeker concurs that much of the content of the works of Herodotus are literary devices.[48][41]

However, a recent discovery of a baris (described in The Histories) during an excavation of the sunken Egyptian port city of Thonis-Heracleion lends credence to Herodotus's travels and storytelling.[57]

Herodotus' contribution to the history and ethnography of ancient Egypt and Africa was especially valued by various historians of the field (such as Constantin François de Chassebœuf, comte de Volney, W. E. B. Du Bois, Pierre Montet, Martin Bernal, Basil Davidson, Derek A. Welsby, Henry T. Aubin). Many scholars explicitly mention the reliability of Herodotus's work (such as on the Nile Valley) and demonstrate corroboration of Herodotus' writings by modern scholars. A. H. L. Heeren quoted Herodotus throughout his work and provided corroboration by scholars regarding several passages (source of the Nile, location of Meroë, etc.).[58]

Cheikh Anta Diop provides several examples (like the inundations of the Nile) which, he argues, support his view that Herodotus was "quite scrupulous, objective, scientific for his time." Diop argues that Herodotus "always distinguishes carefully between what he has seen and what he has been told." Diop also notes that Strabo corroborated Herodotus' ideas about the Black Egyptians, Ethiopians, and Colchians.[59][60] Martin Bernal has relied on Herodotus "to an extraordinary degree" in his controversial book Black Athena.[61]

British egyptologist Derek A. Welsby said that "archaeology graphically confirms Herodotus's observations."[62] To further his work on the Egyptians and Assyrians, historian and fiction writer Henry T. Aubin used Herodotus' accounts in various passages. For Aubin, Herodotus was "the author of the first important narrative history of the world."[63]

Scientific reasoning edit

On geography edit

Herodotus provides much information about the nature of the world and the status of science during his lifetime, often engaging in private speculation likewise. For example, he reports that the annual flooding of the Nile was said to be the result of melting snows far to the south, and he comments that he cannot understand how there can be snow in Africa, the hottest part of the known world, offering an elaborate explanation based on the way that desert winds affect the passage of the Sun over this part of the world (2:18ff). He also passes on reports from Phoenician sailors that, while circumnavigating Africa, they "saw the sun on the right side while sailing westwards", although, being unaware of the existence of the southern hemisphere, he says that he does not believe the claim. Owing to this brief mention, which is included almost as an afterthought, it has been argued that Africa was circumnavigated by ancient seafarers, for this is precisely where the sun ought to have been.[64] His accounts of India are among the oldest records of Indian civilization by an outsider.[65][66][67]

On biology edit

After journeys to India and Pakistan, French ethnologist Michel Peissel claimed to have discovered an animal species that may illuminate one of the most bizarre passages in the Histories.[68] In Book 3, passages 102 to 105, Herodotus reports that a species of fox-sized, furry "ants" lives in one of the far eastern, Indian provinces of the Persian Empire. This region, he reports, is a sandy desert, and the sand there contains a wealth of fine gold dust. These giant ants, according to Herodotus, would often unearth the gold dust when digging their mounds and tunnels, and the people living in this province would then collect the precious dust. Later Pliny the Elder would mention this story in the gold mining section of his Naturalis Historia.

Peissel reports that, in an isolated region of northern Pakistan on the Deosai Plateau in Gilgit–Baltistan province, there is a species of marmot – the Himalayan marmot, a type of burrowing squirrel – that may have been what Herodotus called giant ants. The ground of the Deosai Plateau is rich in gold dust, much like the province that Herodotus describes. According to Peissel, he interviewed the Minaro tribal people who live in the Deosai Plateau, and they have confirmed that they have, for generations, been collecting the gold dust that the marmots bring to the surface when they are digging their burrows.

Peissel offers the theory that Herodotus may have confused the old Persian word for "marmot" with the word for "mountain ant." Research suggests that Herodotus probably did not know any Persian (or any other language except his native Greek) and was forced to rely on many local translators when travelling in the vast multilingual Persian Empire. Herodotus did not claim to have personally seen the creatures which he described.[68][69] Herodotus did, though, follow up in passage 105 of Book 3 with the claim that the "ants" are said to chase and devour full-grown camels.

Accusations of bias edit

Some "calumnious fictions" were written about Herodotus in a work titled On the Malice of Herodotus by Plutarch, a Chaeronean by birth, (or it might have been a Pseudo-Plutarch, in this case "a great collector of slanders"), including the allegation that the historian was prejudiced against Thebes because the authorities there had denied him permission to set up a school.[70] Similarly, in a Corinthian Oration, Dio Chrysostom (or yet another pseudonymous author) accused the historian of prejudice against Corinth, sourcing it in personal bitterness over financial disappointments[71] – an account also given by Marcellinus in his Life of Thucydides.[72] In fact, Herodotus was in the habit of seeking out information from empowered sources within communities, such as aristocrats and priests, and this also occurred at an international level, with Periclean Athens becoming his principal source of information about events in Greece. As a result, his reports about Greek events are often coloured by Athenian bias against rival states – Thebes and Corinth in particular.[73]

Use of sources and sense of authority edit

It is clear from the beginning of Book 1 of the Histories that Herodotus utilizes (or at least claims to utilize) various sources in his narrative. K. H. Waters relates that "Herodotos did not work from a purely Hellenic standpoint; he was accused by the patriotic but somewhat imperceptive Plutarch of being philobarbaros, a pro-barbarian or pro-foreigner."[74]

Herodotus at times relates various accounts of the same story. For example, in Book 1 he mentions both the Phoenician and the Persian accounts of Io.[75] However, Herodotus at times arbitrates between varying accounts: "I am not going to say that these events happened one way or the other. Rather, I will point out the man who I know for a fact began the wrong-doing against the Greeks."[76] Again, later, Herodotus claims himself as an authority: "I know this is how it happened because I heard it from the Delphians myself."[77]

Throughout his work, Herodotus attempts to explain the actions of people. Speaking about Solon the Athenian, Herodotus states "[Solon] sailed away on the pretext of seeing the world, but it was really so that he could not be compelled to repeal any of the laws he had laid down."[78] Again, in the story about Croesus and his son's death, when speaking of Adrastus (the man who accidentally killed Croesus' son), Herodotus states: "Adrastus ... believing himself to be the most ill-fated man he had ever known, cut his own throat over the grave."[79]

Herodotus and myth edit

Although Herodotus considered his "inquiries" a serious pursuit of knowledge, he was not above relating entertaining tales derived from the collective body of myth, but he did so judiciously with regard for his historical method, by corroborating the stories through enquiry and testing their probability.[80] While the gods never make personal appearances in his account of human events, Herodotus states emphatically that "many things prove to me that the gods take part in the affairs of man" (IX, 100).

In Book One, passages 23 and 24, Herodotus relates the story of Arion, the renowned harp player, "second to no man living at that time," who was saved by a dolphin. Herodotus prefaces the story by noting that "a very wonderful thing is said to have happened," and alleges its veracity by adding that the "Corinthians and the Lesbians agree in their account of the matter." Having become very rich while at the court of Periander, Arion conceived a desire to sail to Italy and Sicily. He hired a vessel crewed by Corinthians, whom he felt he could trust, but the sailors plotted to throw him overboard and seize his wealth. Arion discovered the plot and begged for his life, but the crew gave him two options: that either he kill himself on the spot or jump ship and fend for himself in the sea. Arion flung himself into the water, and a dolphin carried him to shore.[81]

Herodotus clearly writes as both historian and teller of tales. Herodotus takes a fluid position between the artistic story-weaving of Homer and the rational data-accounting of later historians. John Herington has developed a helpful metaphor for describing Herodotus's dynamic position in the history of Western art and thought – Herodotus as centaur:

The human forepart of the animal ... is the urbane and responsible classical historian; the body indissolubly united to it is something out of the faraway mountains, out of an older, freer and wilder realm where our conventions have no force.[82]

Herodotus is neither a mere gatherer of data nor a simple teller of tales – he is both. While Herodotus is certainly concerned with giving accurate accounts of events, this does not preclude for him the insertion of powerful mythological elements into his narrative, elements which will aid him in expressing the truth of matters under his study. Thus to understand what Herodotus is doing in the Histories, we must not impose strict demarcations between the man as mythologist and the man as historian, or between the work as myth and the work as history. As James Romm has written, Herodotus worked under a common ancient Greek cultural assumption that the way events are remembered and retold (e.g. in myths or legends) produces a valid kind of understanding, even when this retelling is not entirely factual.[83] For Herodotus, then, it takes both myth and history to produce truthful understanding.

Legacy edit

On the legacy of The Histories of Herodotus, historian Barry S. Strauss writes:

He is simply one of the greatest storytellers who ever wrote. His narrative ability is one of the reasons ... those who call Herodotus the father of history. Now that title is one that he richly deserves. A Greek who lived in the fifth century BC, Herodotus was a pathfinder. He traveled the eastern Mediterranean and beyond to do research into human affairs: from Greece to Persia, from the sands of Egypt to the Scythian steppes, and from the rivers of Lydia to the dry hills of Sparta. The Greek for "research" is historia, where our word "history" comes from ... Herodotus is a great historian. His work holds up very well when judged by the yardstick of modern scholarship. But he is more than a historian. He is a philosopher with three great themes: the struggle between East and West, the power of liberty, and the rise and fall of empires. Herodotus takes the reader from the rise of the Persian Empire to its crusade against Greek independence, and from the stirrings of Hellenic self-defense to the beginnings of the overreach that would turn Athens into a new empire of its own. He goes from the cosmos to the atom, ranging between fate and the gods, on the one hand, and the ability of the individual to make a difference, on the other. And then there is the sheer narrative power of his writing ... The old master keeps calling us back.[84]

In popular culture edit

Historical novels sourcing material from Herodotus

- Pressfield, S. Gates of Fire.

Novel has the Battle of Thermopylae from Book VII as its centrepiece.

- Prus, B. Pharaoh.

Incorporates the Labyrinth scenes inspired by Herodotus' description in Book II of The Histories.

- Wolfe, G. Soldier of the Mist.

First of a series of novels by a popular fantasy author.

Critical editions edit

- Herodotus (1908) [c. 430 BC]. "Tomvs prior: Libros I-IV continens". In Hude, C. (ed.). Herodoti Historiae. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Herodotus (1908) [c. 430 BC]. "Tomvs alter: Libri V-IX continens". In Hude, C. (ed.). Herodoti Historiae. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Herodotus (1987) [c. 430 BC]. Rosén, H.B. (ed.). Herodoti historiae. Vol. I: Libros I-IV continens. Leipzig, DE. doi:10.1515/9783110965926. ISBN 9783598714030.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Herodotus (1997) [c. 430 BC]. Rosén, H.B. (ed.). Herodoti historiae, Volumen II, Libri V-IX. Indices. Vol. II: Libros V-IX continens indicibus criticis adiectis. Stuttgart, DE. doi:10.1515/9783110965919. ISBN 978-3-598-71404-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Translations edit

- Herodotus (1849) [c. 430 BC]. Histories (full text). Translated by Cary, H. New York Harper – via Internet Archive (archive.org).

- Herodotus (1858). Book I – Book IX (full text, all books). Translated by Rawlinson, G. – via classics.mit.edu.

- Herodotus (1904). Histories (full text). Translated by Macaulay, G.C. – via Project Gutenberg (gutenberg.org).

- vol. 1.

- vol. 2.

- Herodotus (1920–1925). "Histories" (full text). Translated by Godley, Alfred Denis. Cambridge, MA.

- vol. 1. librivox (audiobook).

- vol. 2. librivox (audiobook).

- vol. 3. librivox (audiobook).

- Volume I : Books 1–2. 1920.

- Volume II : Books 3–4. 1921.

- Volume III : Books 5–7. 1922.

- Volume IV : Books 8–9. 1925.

- Herodotus (1954) [c. 430 BC, 1972, 1996, 2003]. "excerpts". In Burn, A.R.; Marincola, John (eds.). The Histories. Translated by de Sélincourt, A. (revised once ed.). Archived from the original on 2015-05-04. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Herodotus (1958) [c. 430 BC]. The Histories. Translated by Carter, Harry.

- Herodotus (1992) [c. 430 BC]. The Histories. Translated by Blanco, Walter; Roberts, J.T.

- Herodotus (1998) [c. 430 BC]. The Histories. Translated by Waterfield, R.

- Herodotus (2003) [c. 430 BC]. The Histories (full text).

- Herodotus (2007) [c. 430 BC]. Strassler, Robert B. (ed.). The Histories. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 9781400031146.

- Herodotus (2013) [c. 430 BC]. The Histories. Translated by Holland, Tom. The Penguin Group.[permanent dead link]

- Herodotus (2014) [c. 430 BC]. The Histories. Translated by Mensch, Pamela. with notes by James Romm.

Manuscripts edit

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 18

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 19

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 2099, early 2nd century CE – fragment of Book VIII

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Ancient Greek: [hi.storˈi.ai̯]

- ^ Herodotus (Book II, 68) claimed that the trochilus bird visited the crocodile, which opened its mouth in what would now be called a cleaning symbiosis to eat leeches. A modern survey of the evidence finds only occasional reports of sandpipers "removing leeches from the mouth and gular scutes and snapping at insects along the reptile's body."[5]

- ^ "In the scheme and plan of his work, in the arrangement and order of its parts, in the tone and character of the thoughts, in ten thousand little expressions and words, the Homeric student appears."[18]

- ^ Boedeker comments on Herodotus's use of literary devices.[41]

References edit

- ^ a b Herodotus (1987) [c. 430 BC]. The History Ἱστορίαι [The History]. Translated by Gren, David. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 0-226-32770-1.

- ^ Herodotus; Arnold, John H. (2000). History: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-19-285352-X.

- ^ Fehling, Detlev (1989). "Some demonstrably false source citations". Herodotus and His 'Sources' . Francis Cairns, Ltd. 50–57. ISBN 0-905205-70-7.

Lindsay, Jack (1974). "Helen in the Fifth Century". Helen of Troy Rowman and Littlefield. 133–134. ISBN 0-87471-581-4 - ^ Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by A. D. Godley, Harvard University Press, 1920, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0126:book=1:chapter=94.

- ^ Macfarland, Craig G.; Reeder, W. G. (1974). "Cleaning symbiosis involving Galapagos tortoises and two species of Darwin's finches". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 34 (5): 464–483. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1974.tb01816.x. PMID 4454774.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (March 19, 2019). "2,500 Years Ago, Herodotus Described a Weird Ship. Now, Archaeologists Have Found it". Live Science. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ Kim, Lawrence (2010). "Homer, poet and historian". Homer Between History and Fiction in Imperial Greek Literature. Cambridge University Press. 30-35 ISBN 978-0-521-19449-5.

Allan, Williams (2008). "Introduction". Helen. Cambridge University Press. 22-24 ISBN 0-521-83690-5.

Lindsay, Jack (1974). "Helen in the Fifth Century". Helen of Troy. Rowman and Littlefield. 135-138. ISBN 0-87471-581-4 - ^ "Herodotus, The Histories, Book 6, chapter 100, section 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- ^ a b Murray (1986), p. 188

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.143, 6.137

- ^ Preparation of the Gospel, X, 3

- ^ Immerwahr (1985), pp. 430, 440

- ^ Immerwahr (1985), p. 431

- ^ Burn (1972), pp. 22–23

- ^ Immerwahr (1985), p. 430

- ^ Immerwahr (1985), pp. 427, 432

- ^ Richard Jebb (ed), Antigone, Cambridge University Press, 1976, pp. 181–182, n. 904–920

- ^ Rawlinson (1859), p. 6

- ^ Murray (1986), pp. 190–191

- ^ Blanco (2013), p. 5

- ^ Gould (1989), p. 64

- ^ Homer, Iliad, trans. Stanley Lombardo (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1997): 1, Bk. 1, lines 9–16.

- ^ Gould (1989), p. 65

- ^ Gould (1989), p. 67

- ^ Gould (1989), pp. 67–70

- ^ Gould (1989), p. 71

- ^ Gould (1989), pp. 72–73

- ^ Gould (1989), pp. 75–76

- ^ Gould (1989), pp. 76–78

- ^ Gould (1989), pp. 77–78

- ^ Marincola (2001), p. 59

- ^ Roberts (2011), p. 2

- ^ Sparks (1998), p. 58

- ^ Asheri, Lloyd & Corcella (2007)

- ^ Cameron (2004), p. 156

- ^ Neville Morley: The Anti-Thucydides: Herodotus and the Development of Modern Historiography. In: Jessica Priestly and Vasiliki Zali (eds.): Brill's Companion to the Reception of Herodotus in Antiquity and Beyond. Brill, Leiden and Boston 2016, pp. 143–166, here especially p. 148 ff.

- ^ Vassiliki Zali: Herodotus and His Successors: The Rhetoric of the Persian Wars in Thucydides and Xenophon. In: Priestly and Zali (eds.): Brill's Companion to the Reception of Herodotus in Antiquity and Beyond. Brill, Leiden and Boston 2016, pp. 34–58, here p. 38.

- ^ Fehling (1994), p. 2

- ^ Fehling (1989)

- ^ Fehling (1989), pp. 4, 53–54

- ^ a b Boedeker (2000), pp. 101–102

- ^ Saltzman (2010)

- ^ Archambault (2002), p. 171

- ^ Farley (2010), p. 21

- ^ a b Lloyd (1993), p. 4

- ^ a b Fehling (1994), p. 13

- ^ a b Nielsen (1997), pp. 42–43

- ^ a b c Marincola (2001), p. 34

- ^ a b Dalley (2003)

- ^ a b Baragwanath & de Bakker (2010), p. 19

- ^ a b Dalley (2013)

- ^ Mikalson (2003), pp. 198–200

- ^ a b Burn (1972), p. 10

- ^ a b Jones (1996)

- ^ a b Murray (1986), p. 189

- ^ Fehling (1994), pp. 4–6

- ^ Solly, Meilan. "Wreck of Unusual Ship Described by Herodotus Recovered From Nile Delta". Smithsonian.

- ^ Heeren (1838), pp. 13, 379, 422–424

- ^ Diop (1981), p. 1

- ^ Diop (1974), p. 2

- ^ Norma Thompson: Herodotus and the Origins of the Political Community: Arion's Leap. Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1996, p. 113.

- ^ Welsby (1996), p. 40

- ^ Aubin (2002), pp. 94–96, 100–102, 118–121, 141–144, 328, 336

- ^ "Herodotus on the First Circumnavigation of Africa". Livius.org. 1996. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ The Indian Empire. Vol. 2. 1909. p. 272 – via Digital South Asia Library.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Jain, Meenakshi (1 January 2011). The India They Saw: Foreign Accounts. Vol. 1–4. Delhi: Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-8430-106-9.

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1981). The Classical Accounts of India: Being a Compilation of the English Translations of the Accounts Left by Herodotus, Megasthenes, Arrian, Strabo, Quintus, Diodorus, Siculus, Justin, Plutarch, Frontinus, Nearchus, Apollonius, Pliny, Ptolemy, Aelian, and Others with Maps. Calcutta: Firma KLM. pp. 504. OCLC 247581880.

- ^ a b Peissel (1984)

- ^ Simons, Marlise (25 November 1996). "Himalayas offer clue to legend of gold-digging 'ants'". The New York Times. p. 5. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Rawlinson (1859), pp. 13–14

- ^ "Dio Chrysostom Orat. xxxvii, p11". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ Marcellinus, Life of Thucydides

- ^ Burn (1972), pp. 8, 9, 32–34

- ^ Waters (1985), p. 3

- ^ Blanco (2013), pp. 5–6, §1.1, 1.5

- ^ Blanco (2013), p. 6, §1.5

- ^ Blanco (2013), p. 9, §1.20

- ^ Blanco (2013), p. 12, §1.29

- ^ Blanco (2013), p. 17, §1.45, ¶2

- ^ Wardman (1960)

- ^ Histories 1.23–24.

- ^ Romm (1998), p. 8

- ^ Romm (1998), p. 6

- ^ Strauss, B.S. (14 June 2014). "One of the greatest storytellers who ever lived". Off the Shelf (offtheshelf.com).

Sources edit

- Archambault, Paul (2002). "Herodotus (c. 480 – c. 420)". In della Fazia Amoia, Alba; Knapp, Bettina Liebowitz (eds.). Multicultural Writers from Antiquity to 1945: a Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 168–172. ISBN 978-0-313-30687-7.

- Asheri, David; Lloyd, Alan; Corcella, Aldo (2007). A Commentary on Herodotus, Books 1–4. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814956-9.

- Aubin, Henry (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press. ISBN 978-1-56947-275-0.

- Baragwanath, Emily; de Bakker, Mathieu (2010). Herodotus. Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-980286-9.

- Herodotus; Blanco, Walter (2013). The Histories. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-93397-0.

- Boedeker, Deborah (2000). "Herodotus' genre(s)". In Depew, Mary; Obbink, Dirk (eds.). Matrices of Genre: Authors, canons, and society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 97–114. ISBN 978-0-674-03420-4.

- Burn, A.R. (1972). Herodotus: The Histories. London, UK: Penguin Classics.

- Cameron, Alan (2004). Greek Mythography in the Roman World. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803821-4.

- Dalley, S. (2003). "Why did Herodotus not mention the Hanging Gardens of Babylon?". In Derow, P.; Parker, R. (eds.). Herodotus and his World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 171–189. ISBN 978-0-19-925374-6.

- Dalley, S. (2013). The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: An elusive world-wonder traced. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966226-5.

- Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 978-1-55652-072-3.

- Diop, Cheikh Anta (1981). Civilization or Barbarism. Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 978-1-55652-048-8.

- Evans, J.A.S (1968). "Father of History or Father of Lies: The reputation of Herodotus". Classical Journal. 64: 11–17.

- Farley, David G. (2010). Modernist Travel Writing: Intellectuals abroad. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-7228-7.

- Fehling, Detlev (1989) [1971]. Herodotos and His 'Sources': Citation, invention, and narrative art. Arca Classical and Medieval Texts, Papers, and Monographs. Vol. 21. Translated by Howie, J.G. Leeds, UK: Francis Cairns. ISBN 978-0-905205-70-0.

- Fehling, Detlev (1994). "The art of Herodotus and the margins of the world". In von Martels, Z.R.W.M. (ed.). Travel Fact and Travel Fiction: Studies on fiction, literary tradition, scholarly discovery, and observation in travel writing. Brill's studies in intellectual history. Vol. 55. Leiden, NL: Brill. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-90-04-10112-8.

- Gould, John (1989). Herodotus. Historians on historians. London, UK: George Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-79339-7.

- Heeren, A.H.L. (1838). Historical Researches into the Politics, Intercourse, and Trade of the Carthaginians, Ethiopians, and Egyptians. Oxford, UK: D.A. Talboys. ASIN B003B3P1Y8.

- Immerwahr, Henry R. (1985). "Herodotus". In Easterling, P.E.; Knox, B.M.W. (eds.). Greek Literature. The Cambridge History of Classical Greek Literature. Vol. 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21042-3.

- Jones, C.P. (1996). "ἔθνος and γένος in Herodotus". The Classical Quarterly. new series. 46 (2): 315–320. doi:10.1093/cq/46.2.315.

- Jain, Meenakshi (2011). The India They Saw: Foreign accounts. Delhi, IN: Ocean Books. ISBN 978-81-8430-106-9.

- Lloyd, Alan B. (1993). Herodotus. Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain; Book II. Vol. 43. Leiden, NL: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-07737-9.

- Majumdar, R.C. (1981). The Classical accounts of India. Calcutta, IN: Firma KLM. ISBN 978-0-8364-0704-4.

Being a compilation of the English translations of the accounts left by Herodotus, Megasthenes, Arrian, Strabo, Quintus, Diodorus, Siculus, Justin, Plutarch, Frontinus, Nearchus, Apollonius, Pliny, Ptolemy, Aelian, and others with maps.

- Marincola, John (2001). Greek Historians. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922501-9.

- Mikalson, Jon D. (2003). Herodotus and Religion in the Persian Wars. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2798-7.

- Murray, Oswyn (1986). "Greek historians". In Boardman, John; Griffin, Jasper; Murray, Oswyn (eds.). The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 186–203. ISBN 978-0-19-872112-3.

- Nielsen, Flemming A.J. (1997). The Tragedy in History: Herodotus and the deuteronomistic history. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85075-688-0.

- Peissel, Michel (1984). The Ants' Gold: The discovery of the Greek el Dorado in the Himalayas. Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-272514-9.

- Rawlinson, George (1859). The History of Herodotus. Vol. 1. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company.

- Roberts, Jennifer T. (2011). Herodotus: A very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957599-2.

- Romm, James (1998). Herodotus. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07229-7.

- Saltzman, Joe (2010). "Herodotus as an ancient journalist: Reimagining antiquity's historians as journalists". The IJPC Journal. 2: 153–185.

- Sparks, Kenton L. (1998). Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the study of ethnic sentiments and their expression in the Hebrew Bible. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-033-0.

- Wardman, A.E. (1960). "Myth in Greek historiography". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 9 (4): 403–413. JSTOR 4434671.

- Waters, K.H. (1985). Herodotos the Historian: His problems, methods, and originality. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1928-1.

- Welsby, Derek (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-0986-2.

External links edit

- Herodotus. "History". Classics dept. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. — Complete online text

- Herodotus. "History". Classics dept. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. — Searchable textfile

- Herodotus. "History". Perseus. — Complete online text

- Histories public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- The Histories (online audiobook) (unabridged ed.) – via Internet Archive (archive.org).

- Herodotus. "The 28 Logoi". Histories. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)

- Sheridan, Paul (2015-08-17). "The Inessential Guide to Herodotus". Anecdotes from Antiquity. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

- Herodotus. "Books V–VIII". Histories. Translated by Godley, A.D. Direct link to PDF Archived 2013-05-23 at the Wayback Machine (14 MB)