Summary

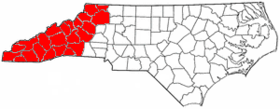

Western North Carolina (often abbreviated as WNC) is the region of North Carolina which includes the Appalachian Mountains; it is often known geographically as the state's Mountain Region. It contains the highest mountains in the Eastern United States, with 125 peaks rising to over 5,000 feet (1,500 meters) in elevation. Mount Mitchell at 6,684 feet (2,037 meters), is the highest peak of the Appalachian Mountains and mainland eastern North America. The population of the 23 most commonly associated counties for the region, as measured by the 2020 U.S. Census, is 1,149,405.[1] [2] The region accounts for approximately 11% of North Carolina's total population.

Located east of the Tennessee state line and west of the Piedmont, Western North Carolina contains few major urban centers. Asheville, located in the region's center, is the area's largest city and most prominent commercial hub. The Foothills region of the state is loosely defined as the area along Western North Carolina's eastern boundary; this region consists of a transitional terrain of hills between the Appalachians and Piedmont Plateau of central North Carolina.

Areas in the northwest portion of the Western North Carolina region, including Boone and Blowing Rock, commonly use the nickname "The High Country". The term Land of the Sky (or Land-of-Sky) is a common nickname for the Asheville area. The term is derived from the title of the novel, Land of the Sky (1876), written by Mrs. Frances Tiernan, under the pseudonym Christian Reid. She often refers in this book to the Great Smoky Mountains and Blue Ridge Mountains, the two main ranges in Western North Carolina. The Asheville area regional government body, the Land-of-Sky Regional Council, uses this nickname.

The federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) have a reserve in this region known as Qualla Boundary; it is situated adjacent to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Their capital is at Cherokee, North Carolina. This region, taking in today's southeastern Tennessee, western North and South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia, is considered the homeland of the historic Cherokee. Many of the people were forcibly removed in the late 1830s in the Trail of Tears to Indian Territory, but others remained; their descendants make up the EBCI, among the largest of recognized tribes. Sixteen earthwork mounds or their sites, built by indigenous peoples, have been listed in state archeological records in the eleven westernmost counties. Archeological and related research in the early 21st century has revealed that there may be as many as 50 such prehistoric mounds in this area, which were long central to Cherokee towns and culture.[3]

Subregions edit

Far West edit

The southwestern and far west part of Western North Carolina all lie within the Appalachian Mountain chain. Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak in the state, as well as eastern North America, is located here. Asheville is the major urban hub of far western North Carolina. This area also includes a few hydroelectric projects managed by the Tennessee Valley Authority, including Fontana Dam. Tourism, especially outdoor ventures such as canoeing, whitewater rafting, camping, and fishing are important for many local economies.

High country edit

The northern counties in Western North Carolina are commonly known as the state's High Country.[4] Centered on Boone, the High Country has the area's most popular ski resorts, including Ski Beech, Appalachian Ski Mountain, and Sugar Mountain.[5] The area also features such attractions, historical sites, and geological formations as Linville Caverns, Grandfather Mountain, and Blowing Rock. Education, skiing, tourism, and Christmas tree farming are among this area's most prominent industries, although agriculture and raising livestock also remain important.[5] The counties that make up the High Country are: Alleghany, Ashe, Avery, Mitchell, Watauga, Wilkes, and Yancey.[6]

Foothills edit

The Foothills is a region of transitional terrain between the Piedmont Plateau and the Appalachian Mountains, extending from the lower edge of the Blue Ridge escarpment into the upper Catawba, Yadkin, Broad, Saluda, and Savannah River valleys. The eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge drop sharply to the foothills section, going from 3,500 to 4,000 feet (1,000–1,200 m) at the top to 1,000–1,500 feet at the base. The foothills region contains numerous lower peaks and isolated mountain ranges, such as the South Mountains, Brushy Mountains, and Stone Mountain State Park. The foothills are divided into many small river and creek valleys where much of the region's population lives. Although no large cities are located in the foothills, the subregion contains many smaller cities and towns.

These towns were often developed by European Americans around a single industry, such as furniture or textiles, which depended on local waterpower as their energy sources. In the late 20th century, many of these industries and their associated jobs moved offshore to other countries due to globalization, although they still remain prevalent in some foothill areas. The towns that depended upon them economically, often suffered from job and population losses of people moving to areas of more economic opportunity. Some areas of the foothills have developed newer economies, including manufacturing, food distribution, utilities, and health care. Many farmers in the northern foothills are poultry farmers. Vineyards have also been developed, along with associated winemaking and popular retail.

Among the towns of the foothills region are: Elkin, Forest City, Glen Alpine, Granite Falls, Hudson, Lake Lure, Rutherfordton, Spindale, Tryon, and Valdese; and the cities of Hickory, Lenoir, Marion, Mount Airy, Shelby, and Morganton. "The southern mountains" refer to the counties bordering South Carolina. The cities/towns of Hendersonville, Brevard, and Columbus are within this area.

Higher education edit

The region has three major public universities: Appalachian State University in Boone, Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, and UNC Asheville in Asheville. All three are part of the University of North Carolina system.

Several small, private colleges and universities are also located in the region. Mars Hill University is located 15 miles (24 km) north of Asheville. Founded in 1856, it is the oldest college or university in Western North Carolina. Montreat College, affiliated with the Presbyterian Church, is located 15 miles (24 km) east of Asheville. Lees-McRae College, located in Banner Elk, is also affiliated with the Presbyterian Church. Warren Wilson College, located in Swannanoa, is noted for its strong pro-environment policies and for being one of the nine work colleges in the United States. Brevard College, located in Brevard, is affiliated with the United Methodist Church. Lenoir-Rhyne University, located in Hickory, is a private liberal arts university affiliated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

Several community college systems serve the region, including Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, Blue Ridge Community College, Caldwell Community College & Technical Institute, Catawba Valley Community College, Haywood Community College, Isothermal Community College, Mayland Community College, McDowell Technical Community College, Southwestern Community College, Tri-County Community College, Western Piedmont Community College, and Wilkes Community College.[7]

Transportation edit

Highways edit

Interstates edit

Three major Interstate highways cross the region: Interstate 40, which traverses east–west, Interstate 77, which runs north–south through the northeastern section of Western North Carolina, and Interstate 26, which traverses north–south (although it is classified as an east–west highway for most of its route and is signed as such). Interstate 240 is the only auxiliary interstate route in the region, and it serves downtown Asheville.

U.S. Highways edit

US 421, a multi-lane expressway, is the major highway in the northwestern part of the state. US 19, US 23, US 64, US 74, and US 441 are the major highways in the far western part of the region. US 70 runs east through the area, connecting Hickory and Asheville. US 221 also runs through the area. This highway, which begins in Perry, Florida, connects the town of Rutherfordton to Jefferson. US 321 runs north from Hickory to Watauga and Avery counties before entering Tennessee.

Blue Ridge Parkway edit

The Blue Ridge Parkway, a National Scenic Byway that is 469 miles long, runs through western North Carolina, starting in Virginia and ending near the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Railroads edit

Two major class 1 railroads serve the region, CSX and Norfolk Southern. In addition, two tourist railroads also operate in the area, the Tweetsie Railroad theme park and the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad.

Airports edit

Asheville Regional Airport (AVL), located southeast of the city of Asheville in Fletcher, serves the area with non-stop jet service to Charlotte, North Carolina; LaGuardia Airport in New York City and nearby Newark, New Jersey; Houston, Texas; Atlanta, Georgia; Orlando Sanford International Airport near Orlando, Florida; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Detroit, Michigan; and O'Hare International Airport in Chicago, Illinois.

Economy edit

Tourism is a major part of the economy in the area, which contains half of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park as well as the Nantahala and Pisgah national forests. Several lakes and dams are scattered throughout Western North Carolina, such as Lake Lure and Fontana Dam. Many visitors travel to the region every summer and autumn from major cities to escape hot weather elsewhere and see the leaves change colors. The timber industry is also a major economic sector.

Appalachian Regional Commission edit

The Appalachian Regional Commission was formed in 1965 to aid economic development in the Appalachian region, which was lagging far behind the rest of the nation on most economic indicators. The Appalachian region, as currently defined by the commission, includes 420 counties in 13 states, including 29 counties in North Carolina. The Commission classifies each county according to five economic qualifications— distressed, at-risk, transitional, competitive, or attainment. "Distressed" counties are considered the most economically endangered and "attainment" counties are the most economically prosperous. The three indicators used for such classification are three-year average unemployment rate, market income per capita, and poverty rate.[8]

In 2003, Appalachian North Carolina— which included most counties of Western North Carolina and two counties in central North Carolina— had a three-year average unemployment rate of 6%, compared with 6.2% statewide and 5.5% nationwide. In 2002, Appalachian North Carolina had a per capita market income of $21,168, compared with $23,443 statewide and $26,420 nationwide. In 2000, Appalachian North Carolina had a poverty rate of 11.7%, compared to 12.3% statewide and 12.4% nationwide.

Only Graham County was designated as "Distressed" in North Carolina. Six— Cherokee, McDowell, Mitchell, Rutherford, Swain, and Yancey— were designated "at-risk." Forsyth County (which is usually grouped as part of central North Carolina) was the only county given the "attainment" designation. Four— Buncombe, Davie, Henderson, and Polk— were designated "competitive." Most Western North Carolina counties were designated "transitional," meaning they lagged behind the national average on one of the three key indicators. Graham County had Appalachian North Carolina's highest poverty rating, with 19.5% of its residents living below the poverty line. Forsyth had Appalachian North Carolina's highest per capita income at $26,987. Watauga County's unemployment rate of 2.3% was lowest of all 420 counties in the Appalachian region.[8]

The changes brought by increased tourism and population growth from retirees and persons migrating to the region have been double-edged. Local businesses have benefited from increased economic revenue, but increases in costs of living and loss of natural habitat to development, can degrade the quality of life for which the region has become notable.

Topography edit

There are 82 mountain peaks between 5,000 and 6,000 feet (1,500 and 1,800 m) in elevation in western North Carolina, and 43 peaks rise to over 6,000 feet (1,800 m). Among the subranges of the Appalachian Mountains located in western North Carolina are the Great Smoky Mountains, Blue Ridge Mountains, South Mountains, Brushy Mountains, Sauratown Mountains, Great Balsam Mountains, Great Craggy Mountains, the Plott Balsams, and the Black Mountains. Mount Mitchell, in the Black Mountains, is, at 6,684 feet (2,037 m), the highest point in eastern North America.[9] Valley and foothills locations typically range from 1,000–2,000 feet (300–610 m) AMSL.

The major rivers in the region include the French Broad River, Nolichucky River, Watauga River, Little Tennessee River, and Hiwassee River flowing into the Tennessee River valley; the New River flowing into the Ohio River valley; and the headwaters and upper valleys of the Catawba River, Yadkin River, Broad River, and Saluda River flowing through the foothills towards the Atlantic. The Eastern Continental Divide runs through the region, dividing Tennessee-bound streams from those flowing through the Carolinas.

Area edit

Counties edit

Western North Carolina is generally considered to consist of 23 counties.[10]

The counties commonly included in the region are as follows:

- Alleghany County

- Ashe County

- Avery County

- Buncombe County

- Burke County

- Caldwell County

- Cherokee County

- Clay County

- Graham County

- Haywood County

- Henderson County

- Jackson County

- Macon County

- Madison County

- McDowell County

- Mitchell County

- Polk County

- Rutherford County

- Swain County

- Transylvania County

- Watauga County

- Wilkes County

- Yancey County

Other counties that fall under various definitions of Western North Carolina include: Alexander County, Catawba County, Cleveland County, Surry County and Yadkin County. When these counties are added, they form a total regional area of roughly 11,750 square miles (30,400 km2). This makes the region roughly the size of Massachusetts.

During the early 1800s the western counties in North Carolina included counties located in the piedmont region, to distinguish them from the eastern counties in North Carolina that were settled earlier. As the western counties became more populated, jurisdictions competed for representation in the North Carolina General Assembly and the Governor's office.[11]

Cities and towns edit

Listed below are communities often considered to be a part of Western North Carolina:

Over 40,000 inhabitants edit

- Asheville

- Hickory (Located in the North Carolina foothills; contains small amounts of territory in Burke and Caldwell Counties)

Over 10,000 inhabitants edit

Fewer than 10,000 inhabitants edit

- Andrews

- Bakersville

- Banner Elk

- Beech Mountain

- Biltmore Forest

- Black Mountain

- Blowing Rock

- Bostic

- Brevard

- Bryson City

- Burnsville

- Cajah's Mountain

- Canton

- Cedar Rock

- Chimney Rock

- Clyde

- Columbus

- Connellys Springs

- Crossnore

- Dillsboro

- Drexel

- Elk Park

- Elkin

- Ellenboro

- Flat Rock

- Fletcher

- Fontana Dam

- Forest City

- Forest Hills

- Franklin

- Gamewell

- Glen Alpine

- Grandfather

- Granite Falls

- Hayesville

- Highlands

- Hildebran

- Hot Springs

- Hudson

- Jefferson

- Lake Lure

- Lake Santeetlah

- Lansing

- Laurel Park

- Long View

- Maggie Valley

- Marion

- Mars Hill

- Marshall

- Mills River

- Montreat

- Murphy

- Newland

- North Wilkesboro

- Old Fort

- Rhodhiss

- Robbinsville

- Ronda

- Rosman

- Ruth

- Rutherford College

- Rutherfordton

- Saluda

- Sawmills

- Seven Devils

- Sparta

- Spindale

- Spruce Pine

- Sugar Mountain

- Sylva

- Tryon

- Valdese

- Weaverville

- Webster

- West Jefferson

- Wilkesboro

- Woodfin

Important unincorporated communities edit

- Brasstown (site of John C. Campbell Folk School)

- Cashiers (a popular tourist area)

- Cherokee (headquarters for the Eastern Band of the Cherokee)

- Collettsville (located near Wilson Creek)

- Cullowhee (site of Western Carolina University's main campus)

- Deals Gap (site of a nationally famous motorcycle and sportscar resort)

- Lake Junaluska (headquarters for the World Methodist Council and site of a United Methodist camp and conference center)

- Linville (a popular recreation area)

- Little Switzerland (located near Blue Ridge Parkway)

See also edit

References edit

- ^ https://www.census.gov/library/stories/state-by-state/north-carolina-population-change-between-census-decade.html

- ^ "Our State Geography". NCPEDIA. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ "WCU Professor Unearths Wealth of Cherokee Culture and History". The Laurel of Asheville. 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "High Country Host – in North Carolina". High Country Host. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ a b Designs, AppNet. "Boone, Blowing Rock, Banner Elk, Beech Mountain, Western North Carolina Guide". www.highcountryinfo.com. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "High Country Council of Government". Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ "Main Campuses". NC Community Colleges. December 16, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Appalachian Regional Commission Online Resource Center. Retrieved: May 15, 2009.

- ^ "GNIS Detail – Mount Mitchell". geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "Our State Geography". NCPEDIA. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Cockrell, David L. (2006). "East-West Rivalry". NCPEDIA. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

External links edit

- North Carolina Mountains travel guide from Wikivoyage