Summary

Hittin (Arabic: حطّين, transliterated Ḥiṭṭīn (Arabic: حِـطِّـيْـن) or Ḥaṭṭīn (Arabic: حَـطِّـيْـن)) was a Palestinian village located 8 kilometers (5 mi) west of Tiberias before it was occupied by Israel during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war when most of its original residents became refugees. As the site of the Battle of Hattin in 1187, in which Saladin reconquered most of Palestine from the Crusaders, it has become an Arab nationalist symbol. The shrine of Nabi Shu'ayb, venerated by the Druze and Sunni Muslims as the tomb of Jethro, is on the village land. The village was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from the 16th century until the end of World War I, when Palestine became part of the British Mandate for Palestine. On July 17 1948, the village was occupied by Israel, after its residents fled out of their homes because of Nazareth's occupation. in later years, the Moshavs Arbel and Kfar Zeitim were erected where Hittin used to be.

Hittin

حطّين Hattin, Hutin | |

|---|---|

Hittin, 1934 | |

| Etymology: from personal name[1] | |

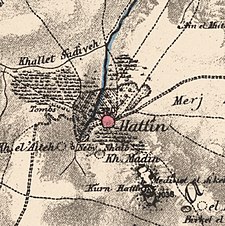

1870s map 1870s map  1940s map 1940s map modern map modern map  1940s with modern overlay map 1940s with modern overlay mapA series of historical maps of the area around Hittin (click the buttons) | |

Hittin Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°48′25″N 35°27′12″E / 32.80694°N 35.45333°E | |

| Palestine grid | 192/245 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Tiberias |

| Date of depopulation | 16–17 July 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 22,764 dunams (22.764 km2 or 8.789 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 1,190[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Fear of being caught up in the fighting |

| Secondary cause | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Arbel, Kefar Zetim |

History edit

Hittin was located on the northern slopes of the double hill known as the "Horns of Hattin." It was strategically and commercially significant due to its location overlooking the Plain of Hittin, which opens onto the coastal lowlands of the Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee) to the east, and to the west is linked by mountain passes leading towards the plains of lower Galilee. These plains, with their east–west passages, served as routes for commercial caravans and military invasions throughout the ages.[5]

Prehistory edit

Archaeological excavations near the village have yielded pottery fragments from the Pottery Neolithic and Chalcolithic period.[6]

Bronze Age to Byzantine period edit

An Early Bronze Age wall was excavated just west of the village.[6] The Arab village may have been built over the Canaanite town of Siddim or Ziddim (Joshua 19:35), which in the third century BCE acquired the Old Hebrew name Kfar Hittin ("village of grain"). It was known as Kfar Hittaya in the Roman period.[7][8] In the 4th century CE, it was a Jewish rabbinical town.[5]

Crusader/Ayyubid and Mamluk periods edit

Hittin was located near the site of the Battle of Hattin, where Saladin defeated the Crusaders in 1187.[9] It is described as having been near the base camp of Saladin's Ayyubid army, by Lieutenant-Colonel Claude Conder in Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1897).[10]

Many prominent figures from the Islamic period in Palestine were born or buried in Hittin, according to early Arab geographers such as Yaqut al-Hamawi (1179–1229) and al-Ansari al-Dimashqi (1256–1327), who himself was called the Shaykh of Hittin. 'Ali al-Dawadari, the writer, Quranic exegetist, and calligrapher, died in the village in 1302.[5]

Ottoman period edit

In 1596, Hittin was a part of the Ottoman Nāḥiyah (Arabic: نَـاحِـيَـة, "Subdistrict") of Tiberias under the Liwā’ (Arabic: لِـوَاء, "District") of Safed. The villagers paid taxes on wheat, barley, olives, goats and beehives.[11][12] In 1646, the bulaydah (Arabic: بُـلَـيْـدَة, "small village") was visited by Evliya Çelebi, who described it as follows: "It is a village in the territory of Safad, consisting of 200 Muslim houses. No Druzes live here. It is like a flourishing little town (bulayda) abounding with vineyards, orchards and gardens. Water and air are refreshing. A large fair is held there once a week, when ten thousand men would gather from the neighbourhood to sell and buy. It is situated in a spacious valley, bordered on both sides by low rocks. There is a mosque, a public bath and a caravanserei in it."[13] Çelebi also reported that there was a shrine called the Teyké Mughraby, inhabited by over one hundred dervishes, which held the grave of Sheikh 'Imād ed-dīn, of the family of the prophet Shu'eib, who was reputed to have lived for two hundred years.[13]

Richard Pococke, who visited in 1727, writes that it is "famous for some pleasant gardens of lemon and orange trees; and here the Turks have a mosque, to which they pay great veneration, having, as they say, a great sheik buried there, whom they call Sede Ishab, who, according to tradition (as a very learned Jew assured me) is Jethro, the father-in-law of Moses."[14] Around this time and until the late 18th century, Hittin was a small village in the autonomous sheikhdom of Zahir al-Umar. In 1767, Zahir's son Sa'id sought to control Hittin and nearby Tur'an, but was defeated by his father. Nonetheless, Zahir granted Sa'id both villages when he pardoned him.[15] A map from Napoleon's invasion of 1799 by Pierre Jacotin showed the place, named as Hattin.[16]

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, a Swiss traveller to Palestine around 1817, noted Hittin as a village,[17] while in 1838 Edward Robinson described it as a small village of stone houses.[18] William McClure Thomson, who visited in the 1850s, found "gigantic" hedges of cactus surrounding Hittin. He reported that visiting the local shrine was considered a cure for insanity.[19]

In 1863 H. B. Tristram, wrote about the "bright faces and bright colours" he saw there, and the "peculiar" costumes: "long tight gowns, or cassocks, of scarlet silk, with diagonal yellow stripes, and generally a bright red and blue or yellow jacket over them; while their cheeks were encircled by dollars and piastres, after Nazareth fashion, and some of the more wealthy wore necklaces of gold coins, with a doubloon for pendant in front."[20] In 1875 Victor Guérin visited the village, mentioning in his writings that there was a local tradition that alleged that the tomb of Jethro (Neby Chaʾīb), the father-in-law of Moses, was to be found in the village.[21]

In 1881, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Hittin as a large well-built village of stone, surrounded by fruit and olive trees. It had an estimated 400-700 villagers, all Muslim, who cultivated the surrounding plain.[22]

A population list from about 1887 showed Hattin to have about 1,350 inhabitants; 100 Jews and 1,250 Muslims.[23] An elementary school was established in the village around 1897.[5]

Conder writes in his Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1897): "The place was surrounded by olives and fruit trees, and a good spring—copious and fresh—flowed on the northwest into the gorge of Wadi Hammam."[10]

In the early 20th-century, some of the village land in the eastern part of the Arbel Valley was sold to Jewish land purchase societies. In 1910, the first Jewish village, Mitzpa, was established there.[5]

British Mandate edit

In 1924, the second Jewish village, Kfar Hittim, was established on land purchased from Hattin.[5]

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the Mandatory Palestine authorities, the population of Hattin was 889; 880 Muslims and 9 Jews,[24] increasing in the 1931 census to 931, all Muslims, in a total of 190 houses.[25]

In 1932 Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam and the local Palestinian leadership affiliated with the Istiqlal party inaugurated a celebration on the anniversary of Saladin's victory in Hittin. Hittin Day, held on August 27 of that year in the courtyard of a school in Haifa, was intended to be an anti-imperialist rally. It was attended by thousands of people from Palestine, Lebanon, Damascus, and Transjordan. The speeches delivered at the event centered around the independence of the Arab world and the importance of unity between Arab Muslims and Christians.[26]

In 1945, Hittin had a population of 1,190 Muslims[2] with a total land area of 22,764 dunams (22.764 km2), of which 22,086 dunams were Arab-owned and 147 dunams were Jewish-owned. The remaining 531 dunams were public property.[3] Cultivable land amounted to 12,426 dunams, while uncultivated land amounted to 10,268 dunams. Of the cultivated land, 1,967 dunams consisted of plantations and irrigable land, and 10,462 dunams were devoted to cereals.[27] The built-up area of the village was 70 dunams and it was populated entirely by Arabs.[28]

1948 War edit

In 1948 the village mukhtar was Ahmad ´Azzam Abu Radi. According to the villagers, they did not feel threatened by their Jewish neighbours at Kfar Hittim, who had visited in November 1947 after the UN vote in favor of the United Nations Partition Plan, and assured the villagers they did not want war.[29][30] There were 50 men in the village who had rifles, with 25-50 rounds of ammunition each.[29]

The villagers grew anxious listening to Radio Amman and Radio Damascus, but remained uninvolved until June 9, when Jewish fighters attacked the neighbouring village of Lubya and were repulsed. Shortly after an Israeli armoured unit, accompanied by infantry, advanced towards the village from the direction of Mitzpa. The attack was rebuffed, but all the local ammunition was used up.[31] On the night of July 16–17, almost all the inhabitants of the village evacuated. Many left for Sallama, between Deir Hanna and Maghar, leaving behind a few elderly people and 30-35 militiamen.[31] On July 17, Hittin was occupied by the Golani Brigade as part of Operation Dekel.[32] When the villagers tried to return, they were chased off. On one occasion, some men and pack animals were killed.[33]

The villagers remained at Salamah for almost a month, but as their food-supply dwindled and their hope of returning faded, they left together for Lebanon.[31] Some resettled in Nazareth. The Israeli government considered allowing 560 internally displaced Palestinians from Hittin and Alut to return to their villages, but the army objected to Hittin for security reasons.[34]

State of Israel edit

In 1949 and 1950, the Jewish villages of Arbel and Kfar Zeitim were founded on the lands of Hittin.[35] In the 1950s, the Druze community in Israel was given official custodianship over the Jethro shrine and 100 dunams of land around it. A request to build housing there for Druze soldiers was rejected. The Druze annual pilgrimage continued to be held and was officially recognized as a religious holiday by Israel in 1954.[36]

According to Ilan Pappé, a resident of Deir Hanna unsuccessfully applied to hold a summer camp on the site of the Hittin mosque, which he hoped to restore. The land is currently used as grazing pasture by the nearby kibbutzim. According to tradition, the mosque was built by Saladin in 1187 to commemorate his victory over the Crusaders.[37] In 2007, an Israeli-Palestinian advocacy organization, Zochrot, protested development plans that encroach on the site and threaten to "swallow up the abandoned remains of the Hittin village."[38]

Nabi Shu'ayb shrine, the tomb of Jethro edit

Ali of Herat wrote (c. 1173) that both Jethro and his wife were buried in Hittin. Yaqut al-Hamawi (1179–1229) wrote that another shrine near Arsuf that claimed to be the tomb of Shu'aib was misidentified.[39] Sunni Muslims and Druze would make ziyarat pilgrimages to Hittin to the Tomb of Shu'ayb, and the Druze celebration at the site attracted members of their religion from other parts of the region of Syria.[36][38][when?]

Demographics edit

In 1596 Hittin had a population of 605.[11] In the 1922 census of Palestine Hittin had a population of 889,[24] which rose to 931 in the 1931 census. There were 190 houses that year.[25][40] In 1945 the population was estimated at 1,190 Arabs.[3] The village had a number of large and influential families; Rabah, 'Azzam, Chabaytah, Sa'adah, Sha'ban, Dahabra, and Houran.[29]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 126

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 12

- ^ a b c d Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 72

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xvii, village #94. Also gives causes of depopulation.

- ^ a b c d e f Khalidi, 1992, p. 521.

- ^ a b Nimrod Getzov, 2007, Hittin, Volume 119, Year 2007, Israel Antiquities Authority

- ^ Jerusalem Talmud, Megillah 1:1 (2a)

- ^ See p. 77 [21] in: Rosenfeld, Ben-Zion (1998). "Places of Rabbinic Settlement in the Galilee, 70-400 C.E.: Periphery versus Center". Hebrew Union College Annual (in Hebrew). 69: 57–103. JSTOR 23508858.

- ^ Lane-Poole, 1898, pp. 197 ff

- ^ a b Conder, 1897, p. 149

- ^ a b Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 190. Quoted in Khalidi, p. 521.

- ^ Note that Rhode, 1979, p. 6 Archived 2019-04-20 at the Wayback Machine writes that the register that Hütteroth and Abdul-Fattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9

- ^ a b Stephan H. Stephan (1936). "Evliya Tshelebi's Travels in Palestine, III". The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 5: 69–73.

- ^ Pococke, 1745, vol 2, p. 67

- ^ Joudah, 1987, pp. 51-52.

- ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 166 Archived 2019-12-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Burckhardt, 1822, pp. 319, 336

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, p. 250

- ^ Thomson, 1859, vol 2, pp. 117-118

- ^ Tristram, 1865, p. 451

- ^ Guérin, 1880, pp. 190-191

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p .360. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 521

- ^ Schumacher, 1888, p. 185

- ^ a b Barron, 1923, Table xi, Sub-district of Tiberias, p. 39

- ^ a b Mills, 1932, p. 82

- ^ Matthews, 2006, p. 153

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 122

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 172

- ^ a b c Nazzal, 1978, p. 84

- ^ A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Mark Tessler, Indiana University Press

- ^ a b c Nazzal, 1978, p. 85

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 423

- ^ Yehuda, Golani Brigade\Intelligence, Daily Summary 25-26.8, IDFA 1096\49\\64. Cited in Morris, 2004, p. 445

- ^ Masalha, 2005, p. 107

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 523

- ^ a b Firro, 1999, p. 236

- ^ Pappé, 2006, p. 218

- ^ a b Nicolle, 1993, p. 91[dead link]

- ^ le Strange, 1890, p.450, p.451

- ^ Bitan, 1982, p. 101.

Bibliography edit

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Bitan, A. (1982). Changes of Settlement in the Eastern Lower Galilee (1800-1976).

- Burckhardt, J.L. (1822). Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. J. Murray.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Conder, C.R. (1897). The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1099 to 1291 A.D. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dalali-Amos, Edna (2009-11-05). "Hittin" (121). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Firro, Kais (1999). The Druzes in the Jewish state: a brief history. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11251-0.

- Getzov, Nimrod (2007-01-15). "Hittin" (110). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartal, Moshe (2010-09-13). "Hittin" (122). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hartal, Moshe (2011-06-16). "Hittin" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Joudah, Ahmad Hasan (1987). Revolt in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: The Era of Shaykh Zahir Al-ʻUmar. Kingston Press. ISBN 9780940670112.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-22. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Lane-Poole, S. (1898). Saladin and the Fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. New York, London: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Masalha, N. (2005). Catastrophe Remembered: Palestine, Israel and the Internal Refugees : Essays in Memory of Edward W. Said (1935-2003). Zed Books. ISBN 1-84277-623-1.

- Matthews, Weldon C. (2006). Confronting an Empire, Constructing a Nation: Arab Nationalists and Popular Politics in Mandate Palestine. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-173-7.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Mokary, Abdalla (2011-12-13). "Hittin" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Nazzal, Nafez (1978). The Palestinian Exodus from Galilee 1948. Beirut: The Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 9780887281280.

- Nicolle, D. (1993). Hattin 1187: Saladin's Greatest Victory. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-284-6.

- Oliphant, L. (1887). Haifa, or Life in Modern Palestine. (p.152 )

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pappé, I. (2006). The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. London and New York: Oneworld. ISBN 1-85168-467-0.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. I. Oxford University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Pococke, R. (1745). A description of the East, and some other countries. Vol. 2. London: Printed for the author, by W. Bowyer.

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schumacher, G. (1900). "Reports from Galilee". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 32: 355–360.

- Thomson, W.M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. Vol. 2 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

- Tristram, H.B. (1865). Land of Israel, A Journal of travel in Palestine, undertaken with special reference to its physical character. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Tsafrir, Y.; Leah Di Segni; Judith Green (1994). (TIR): Tabula Imperii Romani: Judaea, Palaestina. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. p. 163. ISBN 965-208-107-8.

External links edit

- Welcome To Hittin

- Hittin, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 6: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Hittin, from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center