Summary

The Philippines,[g] officially the Republic of the Philippines,[h] is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. In the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of 7,641 islands, with a total area of roughly 300,000 square kilometers, which are broadly categorized in three main geographical divisions from north to south: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The Philippines is bounded by the South China Sea to the west, the Philippine Sea to the east, and the Celebes Sea to the south. It shares maritime borders with Taiwan to the north, Japan to the northeast, Palau to the east and southeast, Indonesia to the south, Malaysia to the southwest, Vietnam to the west, and China to the northwest. It is the world's twelfth-most-populous country, with diverse ethnicities and cultures. Manila is the country's capital, and its most populated city is Quezon City. Both are within Metro Manila.

Republic of the Philippines Republika ng Pilipinas (Filipino) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Maka-Diyos, Maka-tao, Makakalikasan at Makabansa[1] "For God, People, Nature, and Country" | |

| Anthem: "Lupang Hinirang" "Chosen Land" | |

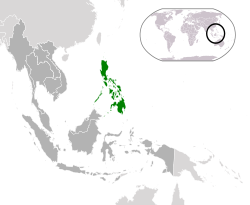

Location of Philippines (green) in ASEAN (dark grey) – [Legend] | |

| Capital | Manila (de jure) Metro Manila[b] (de facto) |

| Largest city | Quezon City |

| Official languages | |

| Recognized regional languages | 19 languages[4] |

National sign language | Filipino Sign Language |

Other recognized languages[c] | Spanish and Arabic |

| Ethnic groups (2020[6]) | |

| Religion (2020)[7] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Filipino (neutral) Filipina (feminine) Pinoy (adjective for certain common nouns) |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Bongbong Marcos | |

| Sara Duterte | |

| Francis Escudero | |

| Martin Romualdez | |

| Alexander Gesmundo | |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from Spain and the United States | |

| June 12, 1898 | |

• Cession | April 11, 1899 |

| November 15, 1935 | |

| July 4, 1946 | |

| February 2, 1987 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 300,000[8][9][e] km2 (120,000 sq mi) (72nd[11]) |

• Water (%) | 0.61[10] (inland waters) |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• 2020 census | |

• Density | 363.45/km2 (941.3/sq mi) (36th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | high (113th) |

| Currency | Philippine peso (₱) (PHP) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PhST) |

| Date format | MM/DD/YYYY DD/MM/YYYY[f] |

| Drives on | right[17] |

| Calling code | +63 |

| ISO 3166 code | PH |

| Internet TLD | .ph |

Negritos, the archipelago's earliest inhabitants, were followed by waves of Austronesian peoples. The adoption of animism, Hinduism with Buddhist influence, and Islam established island-kingdoms ruled by datus, rajas, and sultans. Extensive overseas trade with neighbors such as the late Tang or Song empire brought Chinese people to the archipelago as well, which would also gradually settle in and intermix over the centuries. The arrival of Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer leading a fleet for Castile, marked the beginning of Spanish colonization. In 1543, Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos named the archipelago Las Islas Filipinas in honor of King Philip II of Castile. Spanish colonization via New Spain, beginning in 1565, led to the Philippines becoming ruled by the Crown of Castile, as part of the Spanish Empire, for more than 300 years. Catholic Christianity became the dominant religion, and Manila became the western hub of trans-Pacific trade. Hispanic immigrants from Latin America and Iberia would also selectively colonize. The Philippine Revolution began in 1896, and became entwined with the 1898 Spanish–American War. Spain ceded the territory to the United States, and Filipino revolutionaries declared the First Philippine Republic. The ensuing Philippine–American War ended with the United States controlling the territory until the Japanese invasion of the islands during World War II. After the United States retook the Philippines from the Japanese, the Philippines became independent in 1946. The country has had a tumultuous experience with democracy, which included the overthrow of a decades-long dictatorship in a nonviolent revolution.

The Philippines is an emerging market and a newly industrialized country, whose economy is transitioning from being agricultural to service- and manufacturing-centered. It is a founding member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, ASEAN, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, and the East Asia Summit; it is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement and a major non-NATO ally of the United States. Its location as an island country on the Pacific Ring of Fire and close to the equator makes it prone to earthquakes and typhoons. The Philippines has a variety of natural resources and a globally-significant level of biodiversity.

Etymology

editDuring his 1542 expedition, Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos named the islands of Leyte and Samar "Felipinas" after the Prince of Asturias, later Philip II of Castile. Eventually, the name "Las Islas Filipinas" would be used for the archipelago's Spanish possessions.[18]: 6 Other names, such as "Islas del Poniente" (Western Islands), "Islas del Oriente" (Eastern Islands), Ferdinand Magellan's name, and "San Lázaro" (Islands of St. Lazarus), were used by the Spanish to refer to islands in the region before Spanish rule was established.[19][20][21]

During the Philippine Revolution, the Malolos Congress proclaimed it the República Filipina (the Philippine Republic).[22] American colonial authorities referred to the country as the Philippine Islands (a translation of the Spanish name).[23] The United States began changing its nomenclature from "the Philippine Islands" to "the Philippines" in the Philippine Autonomy Act and the Jones Law.[24] The official title "Republic of the Philippines" was included in the 1935 constitution as the name of the future independent state,[25] and in all succeeding constitutional revisions.[26][27]

History

editPrehistory (pre–900)

editThere is evidence of early hominins living in what is now the Philippines as early as 709,000 years ago.[28] A small number of bones from Callao Cave potentially represent an otherwise unknown species, Homo luzonensis, who lived 50,000 to 67,000 years ago.[29][30] The oldest modern human remains on the islands are from the Tabon Caves of Palawan, U/Th-dated to 47,000 ± 11–10,000 years ago.[31] Tabon Man is presumably a Negrito, among the archipelago's earliest inhabitants descended from the first human migrations out of Africa via the coastal route along southern Asia to the now-sunken landmasses of Sundaland and Sahul.[32]

The first Austronesians reached the Philippines from Taiwan around 2200 BC, settling the Batanes Islands (where they built stone fortresses known as ijangs)[33] and northern Luzon. Jade artifacts have been dated to 2000 BC,[34][35] with lingling-o jade items made in Luzon with raw materials from Taiwan.[36] By 1000 BC, the inhabitants of the archipelago had developed into four societies: hunter-gatherer tribes, warrior societies, highland plutocracies, and port principalities.[37]

Early states (900–1565)

editThe earliest known surviving written record in the Philippines is the early-10th-century AD Laguna Copperplate Inscription, which was written in Old Malay using the early Kawi script with a number of technical Sanskrit words and Old Javanese or Old Tagalog honorifics.[38] By the 14th century, several large coastal settlements emerged as trading centers and became the focus of societal changes.[39] Some polities had exchanges with other states throughout Asia.[40]: 3 [41] Trade with China began during the late Tang dynasty,[42][43] and expanded during the Song dynasty.[44][45][43] Throughout the second millennium AD, some polities were also part of the tributary system of China.[18]: 177–178 [40]: 3 With extensive trade and diplomacy, this brought Southern Chinese merchants and migrants from Southern Fujian, known as "Langlang"[46] and "Sangley" in later years,[47][48] who would gradually settle and intermix in the Philippines. Indian cultural traits such as linguistic terms and religious practices began to spread in the Philippines during the 14th century, via the Indianized Hindu Majapahit Empire.[49][50] By the 15th century, Islam was established in the Sulu Archipelago and spread from there.[39]

Polities founded in the Philippines between the 10th and 16th centuries include Maynila,[51] Tondo, Namayan, Pangasinan, Cebu, Butuan, Maguindanao, Lanao, Sulu, and Ma-i.[52] The early polities typically had a three-tier social structure: nobility, freemen, and dependent debtor-bondsmen.[40]: 3 [53]: 672 Among the nobility were leaders known as datus, who were responsible for ruling autonomous groups (barangays or dulohan).[54] When the barangays banded together to form a larger settlement or a geographically looser alliance,[40]: 3 [55] their more-esteemed members would be recognized as a "paramount datu",[56]: 58 [37] rajah or sultan,[57] and would rule the community.[58] Population density is thought to have been low during the 14th to 16th centuries[56]: 18 due to the frequency of typhoons and the Philippines' location on the Pacific Ring of Fire.[59] Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in 1521, claimed the islands for Spain, and was killed by Lapulapu's men in the Battle of Mactan.[60]: 21 [61]: 261

Spanish and American colonial rule (1565–1934)

editUnification and colonization by the Crown of Castile began when Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpi arrived from New Spain (Spanish: Nueva España) in 1565.[62][63][64]: 20–23 Many Filipinos were brought to New Spain as slaves and forced crew.[65] Whereas many Latin Americans were brought to the Philippines as soldiers and colonists. Spanish Manila became the capital of the Captaincy General of the Philippines and the Spanish East Indies in 1571,[66][67] Spanish territories in Asia and the Pacific.[68] The Spanish invaded local states using the principle of divide and conquer,[61]: 374 bringing most of what is the present-day Philippines under one unified administration.[69][70] Disparate barangays were deliberately consolidated into towns, where Catholic missionaries could more easily convert their inhabitants to Christianity,[71]: 53, 68 [72] which was initially Syncretist.[73] Christianization by the Spanish friars occurred mostly across the settled lowlands over the course of time. From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as a territory of the Mexico City-based Viceroyalty of New Spain; it was then administered from Madrid after the Mexican War of Independence.[74]: 81 Manila became the western hub of trans-Pacific trade[75] by Manila galleons built in Bicol and Cavite.[76][77]

During its rule, Spain nearly bankrupted its treasury quelling indigenous revolts[74]: 111–122 and defending against external military attacks,[78]: 1077 [79] including Moro piracy,[80] a 17th-century war against the Dutch, 18th-century British occupation of Manila, and conflict with Muslims in the south.[81]: 4 [undue weight? – discuss]

Administration of the Philippines was considered a drain on the economy of New Spain,[78]: 1077 and abandoning it or trading it for other territory was debated. This course of action was opposed because of the islands' economic potential, security, and the desire to continue religious conversion in the region.[56]: 7–8 [82] The colony survived on an annual subsidy from the Spanish crown[78]: 1077 averaging 250,000 pesos,[56]: 8 usually paid as 75 tons of silver bullion from the Americas.[83] British forces occupied Manila from 1762 to 1764 during the Seven Years' War, and Spanish rule was restored with the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[64]: 81–83 The Spanish considered their war with the Muslims in Southeast Asia an extension of the Reconquista.[84][85] The Spanish–Moro conflict lasted for several hundred years; Spain conquered portions of Mindanao and Jolo during the last quarter of the 19th century,[86] and the Muslim Moro in the Sultanate of Sulu acknowledged Spanish sovereignty.[87][88]

Philippine ports opened to world trade during the 19th century, and Filipino society began to change.[89][90] Social identity changed, with the term Filipino encompassing all residents of the archipelago instead of solely referring to Spaniards born in the Philippines.[91][92]

Revolutionary sentiment grew in 1872 after 200 locally recruited colonial troops and laborers alongside three activist Catholic priests were executed on questionable grounds.[93][94] This inspired the Propaganda Movement, organized by Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, Graciano López Jaena, and Mariano Ponce, which advocated political reform in the Philippines.[95] Rizal was executed on December 30, 1896, for rebellion, and his death radicalized many who had been loyal to Spain.[96] Attempts at reform met with resistance; Andrés Bonifacio founded the Katipunan secret society, which sought independence from Spain through armed revolt, in 1892.[74]: 137

The Katipunan Cry of Pugad Lawin began the Philippine Revolution in 1896.[97] Internal disputes led to the Tejeros Convention, at which Bonifacio lost his position and Emilio Aguinaldo was elected the new leader of the revolution.[98]: 145–147 The 1897 Pact of Biak-na-Bato resulted in the Hong Kong Junta government in exile. The Spanish–American War began the following year, and reached the Philippines; Aguinaldo returned, resumed the revolution, and declared independence from Spain on June 12, 1898.[99]: 26 In December 1898, the islands were ceded by Spain to the United States with Puerto Rico and Guam after the Spanish–American War.[100][101]

The First Philippine Republic was promulgated on January 21, 1899.[102] Lack of recognition by the United States led to an outbreak of hostilities that, after refusal by the U.S. on-scene military commander of a cease-fire proposal and a declaration of war by the nascent Republic,[i] escalated into the Philippine–American War.[103][104][105][106]

The war resulted in the deaths of 250,000 to 1 million civilians, primarily due to famine and disease.[107] Many Filipinos were transported by the Americans to concentration camps, where thousands died.[108][109] After the fall of the First Philippine Republic in 1902, an American civilian government was established with the Philippine Organic Act.[110] American forces continued to secure and extend their control of the islands, suppressing an attempted extension of the Philippine Republic,[98]: 200–202 [107] securing the Sultanate of Sulu,[111][112] establishing control of interior mountainous areas which had resisted Spanish conquest,[113] and encouraging large-scale resettlement of Christians in once-predominantly-Muslim Mindanao.[114][115]

Commonwealth and World War II (1935–1946)

editCultural developments in the Philippines strengthened a national identity,[116][117]: 12 and Tagalog began to take precedence over other local languages.[71]: 121 Governmental functions were gradually given to Filipinos by the Taft Commission;[78]: 1081, 1117 the 1934 Tydings–McDuffie Act granted a ten-year transition to independence through the creation of the Commonwealth of the Philippines the following year,[118] with Manuel Quezon president and Sergio Osmeña vice president.[119] Quezon's priorities were defence, social justice, inequality, economic diversification, and national character.[78]: 1081, 1117 Filipino (a standardized variety of Tagalog) became the national language,[120]: 27–29 women's suffrage was introduced,[121][61]: 416 and land reform was considered.[122][123][124]

The Empire of Japan invaded the Philippines in December 1941 during World War II,[125] and the Second Philippine Republic was established as a puppet state governed by Jose P. Laurel.[126][127] Beginning in 1942, the Japanese occupation of the Philippines was opposed by large-scale underground guerrilla activity.[128][129][130] Atrocities and war crimes were committed during the war, including the Bataan Death March and the Manila massacre.[131][132] The Philippine resistance and Allied troops defeated the Japanese in 1944 and 1945. Over one million Filipinos were estimated to have died by the end of the war.[133][134] On October 11, 1945, the Philippines became a founding member of the United Nations.[135][136]: 38–41 On July 4, 1946, during the presidency of Manuel Roxas, the country's independence was recognized by the United States with the Treaty of Manila.[136]: 38–41 [137]

Independence (1946–present)

editEfforts at post-war reconstruction and ending the Hukbalahap Rebellion succeeded during Ramon Magsaysay's presidency,[138] but sporadic communist insurgency continued to flare up long afterward.[139] Under Magsaysay's successor, Carlos P. Garcia, the government initiated a Filipino First policy which promoted Filipino-owned businesses.[71]: 182 Succeeding Garcia, Diosdado Macapagal moved Independence Day from July 4 to June 12—the date of Emilio Aguinaldo's declaration—[140] and pursued a claim on eastern North Borneo.[141][142]

In 1965, Macapagal lost the presidential election to Ferdinand Marcos. Early in his presidency, Marcos began infrastructure projects funded mostly by foreign loans; this improved the economy, and contributed to his reelection in 1969.[143]: 58 [144] Near the end of his last constitutionally-permitted term, Marcos declared martial law on September 21, 1972[145] using the specter of communism[146][147][148] and began to rule by decree;[149] the period was characterized by political repression, censorship, and human rights violations.[150][151] Monopolies controlled by Marcos's cronies were established in key industries,[152][153][154] including logging[155] and broadcasting;[61]: 120 a sugar monopoly led to a famine on the island of Negros.[156] With his wife, Imelda, Marcos was accused of corruption and embezzling billions of dollars of public funds.[157][158] Marcos's heavy borrowing early in his presidency resulted in economic crashes, exacerbated by an early 1980s recession where the economy contracted by 7.3 percent annually in 1984 and 1985.[159]: 212 [160]

On August 21, 1983, opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr. (Marcos's chief rival) was assassinated on the tarmac at Manila International Airport.[161] Marcos called a snap presidential election in 1986[162] which proclaimed him the winner, but the results were widely regarded as fraudulent.[163] The resulting protests led to the People Power Revolution,[164][165] which forced Marcos and his allies to flee to Hawaii. Aquino's widow, Corazon, was installed as president[164] and a new constitution was promulgated.[166]

The return of democracy and government reforms which began in 1986 were hampered by national debt, government corruption, and coup attempts.[168][143]: xii, xiii A communist insurgency[169][170] and military conflict with Moro separatists persisted;[171] the administration also faced a series of disasters, including the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991.[167] Aquino was succeeded by Fidel V. Ramos, who liberalized the national economy with privatization and deregulation.[172][173] Ramos's economic gains were overshadowed by the onset of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[174][175] His successor, Joseph Estrada, prioritized public housing[176] but faced corruption allegations[177] which led to his overthrow by the 2001 EDSA Revolution and the succession of Vice President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo on January 20, 2001.[178] Arroyo's nine-year administration was marked by economic growth,[10] but was tainted by corruption and political scandals,[179][180] including electoral fraud allegations during the 2004 presidential election.[181] Economic growth continued during Benigno Aquino III's administration, which advocated good governance and transparency.[182]: 1, 3 [183] Aquino III signed a peace agreement with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) resulting in the Bangsamoro Organic Law establishing an autonomous Bangsamoro region, but a shootout with MILF rebels in Mamasapano delayed passage of the law.[184][185]

Growing public frustration with post-EDSA governance led to the 2016 election[186] of populist Rodrigo Duterte,[187][188] whose presidency saw the decline of liberalism in the country albeit largely retaining liberal economic policies.[189][190] Among Duterte's priorities was aggressively increasing infrastructure spending to spur economic growth;[191][192] the enactment of the Bangsamoro Organic Law;[193] an intensified crackdown on crime and communist insurgencies;[194] and an anti-drug campaign that reduced drug proliferation[195] but that has also led to extrajudicial killings.[196][197] In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic reached the Philippines,[198][199] necessitating nationwide lockdowns that caused a brief but severe economic recession.[200][201] Under a promise of continuing Duterte's policies,[190] Marcos's son, Bongbong Marcos, ran with Duterte's daughter, Sara, and won the 2022 election.[202] Marcos's renewal of a pro-US foreign policy, however, has been viewed as a reversal of Duterte's cordiality with China, and territorial disputes in the South China Sea have since escalated.[203]

Geography

editThe Philippines is an archipelago of about 7,641 islands,[205][206] covering a total area (including inland bodies of water) of about 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 sq mi).[207][208]: 15 [10][e] Stretching 1,850 kilometers (1,150 mi) north to south,[210] from the South China Sea to the Celebes Sea,[211] the Philippines is bordered by the Philippine Sea to the east,[212][213] and the Sulu Sea to the southwest.[214] The country's 11 largest islands are Luzon, Mindanao, Samar, Negros, Palawan, Panay, Mindoro, Leyte, Cebu, Bohol and Masbate, about 95 percent of its total land area.[215] The Philippines' coastline measures 36,289 kilometers (22,549 mi), the world's fifth-longest,[216] and the country's exclusive economic zone covers 2,263,816 km2 (874,064 sq mi).[217]

Its highest mountain is Mount Apo on Mindanao, with an altitude of 2,954 meters (9,692 ft) above sea level.[10] The Philippines' longest river is the Cagayan River in northern Luzon, which flows for about 520 kilometers (320 mi).[218] Manila Bay, on which is the capital city of Manila,[219] is connected to Laguna de Bay[220] (the country's largest lake) by the Pasig River.[221]

On the western fringes of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Philippines has frequent seismic and volcanic activity.[222]: 4 The region is seismically active, and has been constructed by plates converging towards each other from multiple directions.[223][224] About five earthquakes are recorded daily, although most are too weak to be felt.[225] The last major earthquakes were in 1976 in the Moro Gulf and in 1990 on Luzon.[226] The Philippines has 23 active volcanoes; of them, Mayon, Taal, Canlaon, and Bulusan have the largest number of recorded eruptions.[227][208]: 26

The country has valuable[228] mineral deposits as a result of its complex geologic structure and high level of seismic activity.[229][230] It is thought to have the world's second-largest gold deposits (after South Africa), large copper deposits,[231] and the world's largest deposits of palladium.[232] Other minerals include chromium, nickel, molybdenum, platinum, and zinc.[233] However, poor management and law enforcement, opposition from indigenous communities, and past environmental damage have left these resources largely untapped.[231][234]

Biodiversity

editThe Philippines is a megadiverse country,[236][237] with some of the world's highest rates of discovery and endemism (67 percent).[238][239] With an estimated 13,500 plant species in the country (3,500 of which are endemic),[240] Philippine rain forests have an array of flora:[241][242] about 3,500 species of trees,[243] 8,000 flowering plant species, 1,100 ferns, and 998 orchid species[244] have been identified.[245] The Philippines has 167 terrestrial mammals (102 endemic species), 235 reptiles (160 endemic species), 99 amphibians (74 endemic species), 686 birds (224 endemic species),[246] and over 20,000 insect species.[245]

As an important part of the Coral Triangle ecoregion,[247][248] Philippine waters have unique, diverse marine life[249] and the world's greatest diversity of shore-fish species.[250] The country has over 3,200 fish species (121 endemic).[251] Philippine waters sustain the cultivation of fish, crustaceans, oysters, and seaweeds.[252][253]

Eight major types of forests are distributed throughout the Philippines: dipterocarp, beach forest,[254] pine forest, molave forest, lower montane forest, upper montane (or mossy forest), mangroves, and ultrabasic forest.[255] According to official estimates, the Philippines had 7,000,000 hectares (27,000 sq mi) of forest cover in 2023.[256] Logging had been systemized during the American colonial period[257] and deforestation continued after independence, accelerating during the Marcos presidency due to unregulated logging concessions.[258][259] Forest cover declined from 70 percent of the Philippines' total land area in 1900 to about 18.3 percent in 1999.[260] Rehabilitation efforts have had marginal success.[261]

The Philippines is a priority hotspot for biodiversity conservation;[262][236] it has more than 200 protected areas,[263] which was expanded to 7,790,000 hectares (30,100 sq mi) as of 2023[update].[264] Three sites in the Philippines have been included on the UNESCO World Heritage List: the Tubbataha Reef in the Sulu Sea,[265] the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River,[266] and the Mount Hamiguitan Wildlife Sanctuary.[267]

Climate

editThe Philippines has a tropical maritime climate which is usually hot and humid. There are three seasons: a hot dry season from March to May, a rainy season from June to November, and a cool dry season from December to February.[268] The southwest monsoon (known as the habagat) lasts from May to October, and the northeast monsoon (amihan) lasts from November to April.[269]: 24–25 The coolest month is January, and the warmest is May. Temperatures at sea level across the Philippines tend to be in the same range, regardless of latitude; average annual temperature is around 26.6 °C (79.9 °F) but is 18.3 °C (64.9 °F) in Baguio, 1,500 meters (4,900 ft) above sea level.[270] The country's average humidity is 82 percent.[269]: 24–25 Annual rainfall is as high as 5,000 millimeters (200 in) on the mountainous east coast, but less than 1,000 millimeters (39 in) in some sheltered valleys.[268]

The Philippine Area of Responsibility has 19 typhoons in a typical year,[271] usually from July to October;[268] eight or nine of them make landfall.[272][273] The wettest recorded typhoon to hit the Philippines dropped 2,210 millimeters (87 in) in Baguio from July 14 to 18, 1911.[274] The country is among the world's ten most vulnerable to climate change.[275][276]

Government and politics

editThe Philippines has a democratic government, a constitutional republic with a presidential system.[277] The president is head of state and head of government,[278] and is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.[277] The president is elected through direct election by the citizens of the Philippines for a six-year term.[279] The president appoints and presides over the cabinet and officials of various national government agencies and institutions.[280]: 213–214 The bicameral Congress is composed of the Senate (the upper house, with members elected to a six-year term) and the House of Representatives, the lower house, with members elected to a three-year term.[281]

Senators are elected at-large,[281] and representatives are elected from legislative districts and party lists.[280]: 162–163 Judicial authority is vested in the Supreme Court, composed of a chief justice and fourteen associate justices,[282] who are appointed by the president from nominations submitted by the Judicial and Bar Council.[277]

Attempts to change the government to a federal, unicameral, or parliamentary government have been made since the Ramos administration.[283] Philippine politics tends to be dominated by well-known families, such as political dynasties or celebrities,[284][285] and party switching is widely practiced.[286] Corruption is significant,[287][288][289] attributed by some historians to the Spanish colonial period's padrino system.[290][291] The Roman Catholic church exerts considerable but waning[292] influence in political affairs, although a constitutional provision for the separation of Church and State exists.[293]

Foreign relations

editA founding and active member of the United Nations,[136]: 37–38 the Philippines has been a non-permanent member of the Security Council.[294] The country participates in peacekeeping missions, particularly in East Timor.[295][296] The Philippines is a founding and active member of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations)[297][298] and a member of the East Asia Summit,[299] the Group of 24,[300] and the Non-Aligned Movement.[301] The country has sought to obtain observer status in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation since 2003,[302][303] and was a member of SEATO.[304][305] Over 10 million Filipinos live and work in 200 countries,[306][307] giving the Philippines soft power.[159]: 207

During the 1990s, the Philippines began to seek economic liberalization and free trade[308]: 7–8 to help spur foreign direct investment.[309] It is a member of the World Trade Organization[308]: 8 and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.[310] The Philippines entered into the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement in 2010[311] and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership free trade agreement (FTA) in 2023.[312][313] Through ASEAN, the Philippines has signed FTAs with China, India, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.[308]: 15 The country has bilateral FTAs with Japan, South Korea,[314] and four European states: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland.[308]: 9–10, 15

The Philippines has a long relationship with the United States, involving economics, security, and interpersonal relations.[315] The Philippines' location serves an important role in the United States' island chain strategy in the West Pacific;[316][317] a Mutual Defense Treaty between the two countries was signed in 1951, and was supplemented with the 1999 Visiting Forces Agreement and the 2016 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement.[318] The country supported American policies during the Cold War and participated in the Korean and Vietnam wars.[319][320] In 2003, the Philippines was designated a major non-NATO ally.[321] Under President Duterte, ties with the United States weakened in favor of improved relations with China and Russia.[322][323][324] The Philippines relies heavily on the United States for its external defense;[182]: 11 the U.S. has made regular assurances to defend the Philippines,[325] including the South China Sea.[326]

Since 1975, the Philippines has valued its relations with China[327]—its top trading partner,[328] and cooperates significantly with the country.[329][322] Japan is the biggest bilateral contributor of official development assistance to the Philippines;[330][331] although some tension exists because of World War II, much animosity has faded.[81]: 93 Historical and cultural ties continue to affect relations with Spain.[332][333] Relations with Middle Eastern countries are shaped by the high number of Filipinos working in those countries,[334] and by issues related to the Muslim minority in the Philippines;[335] concerns have been raised about domestic abuse and war affecting the approximately 2.5 million overseas Filipino workers in the region.[336][337]

The Philippines has claims in the Spratly Islands which overlap with claims by China, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Vietnam.[338] The largest of its controlled islands is Thitu Island, which contains the Philippines' smallest town.[339] The 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff, after China seized the shoal from the Philippines, led to an international arbitration case[340] which the Philippines eventually won;[341] China rejected the result,[342] and made the shoal a prominent symbol of the broader dispute.[343]

Military

editThe volunteer Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) consist of three branches: the Philippine Air Force, the Philippine Army, and the Philippine Navy.[344][345] Civilian security is handled by the Philippine National Police under the Department of the Interior and Local Government.[346] The AFP had a total manpower of around 280,000 as of 2022[update], of which 130,000 were active military personnel, 100,000 were reserves, and 50,000 were paramilitaries.[347]

In 2023, US$477 million (1.4 percent of GDP) was spent on the Philippine military.[348][349] Most of the country's defense spending is on the Philippine Army, which leads operations against internal threats such as communist and Muslim separatist insurgencies; its preoccupation with internal security contributed to the decline of Philippine naval capability which began during the 1970s.[350] A military modernization program began in 1995[351] and expanded in 2012 to build a more capable defense system.[352]

The Philippines has long struggled against local insurgencies, separatism, and terrorism.[353][354][355] Bangsamoro's largest separatist organizations, the Moro National Liberation Front and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, signed final peace agreements with the government in 1996 and 2014 respectively.[356][357] Other, more-militant groups such as Abu Sayyaf and Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters[358] have kidnapped foreigners for ransom, particularly in the Sulu Archipelago[359][360] and Maguindanao,[358] but their presence has been reduced.[361][362] The Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its military wing, the New People's Army (NPA), have been waging guerrilla warfare against the government since the 1970s and have engaged in ambushes, bombings, and assassinations of government officials and security forces;[363] although shrinking militarily and politically after the return of democracy in 1986,[354][364] the CPP-NPA, through the National Democratic Front of the Philippines, continues to gather public support in urban areas by setting up communist fronts, infiltrating sectoral organizations, and rallying public discontent and increased militancy against the government.[365] The Philippines ranked 104th out of 163 countries in the 2024 Global Peace Index.[366]

Administrative divisions

editThe Philippines is divided into 18 regions, 82 provinces, 146 cities, 1,488 municipalities, and 42,036 barangays.[367] Regions other than Bangsamoro are divided for administrative convenience.[368] Calabarzon was the region with the greatest population as of 2020[update], and the National Capital Region (NCR) was the most densely populated.[369]

The Philippines is a unitary state, with the exception of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM),[370] although there have been steps towards decentralization;[371][372] a 1991 law devolved some powers to local governments.[373]

Economy

editThe Philippine economy is the world's 34th largest, with an estimated 2023[update] nominal gross domestic product of US$435.7 billion.[14] As a newly industrialized country,[374][375] the Philippine economy has been transitioning from an agricultural base to one with more emphasis on services and manufacturing.[374][376] The country's labor force was around 50 million as of 2023[update], and its unemployment rate was 3.1 percent.[377] Gross international reserves totaled US$103.406 billion as of January 2024[update].[378] Debt-to-GDP ratio decreased to 60.2 percent at the end of 2023 from a 17-year high 63.7 percent at the end of the third quarter of that year, and indicated resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic.[379] The country's unit of currency is the Philippine peso (₱[380] or PHP[381]).[382]

The Philippines is a net importer,[308]: 55–56, 61–65, 77, 83, 111 [383] and a debtor nation.[384] As of 2020[update], the country's main export markets were China, the United States, Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore;[385] primary exports included integrated circuits, office machinery and parts, electrical transformers, insulated wiring, and semiconductors.[385] Its primary import markets that year were China, Japan, South Korea, the United States, and Indonesia.[385] Major export crops include coconuts, bananas, and pineapples; it is the world's largest producer of abaca,[208]: 226–242 and was the world's second biggest exporter of nickel ore in 2022,[386] as well as the biggest exporter of gold-clad metals and the biggest importer of copra in 2020.[385]

With an average annual growth rate of six to seven percent since around 2010, the Philippines has emerged as one of the world's fastest-growing economies,[388] driven primarily by its increasing reliance on the service sector.[389] Regional development is uneven, however, with Manila (in particular) gaining most of the new economic growth.[390][391] Remittances from overseas Filipinos contribute significantly to the country's economy;[392][389] they reached a record US$37.20 billion in 2023, accounting for 8.5 percent of GDP.[393] The Philippines is the world's primary business process outsourcing (BPO) center.[394][395] About 1.3 million Filipinos work in the BPO sector, primarily in customer service.[396]

Science and technology

editThe Philippines has one of the largest agricultural-research systems in Asia, despite relatively low spending on agricultural research and development.[397][398] The country has developed new varieties of crops, including rice,[399][400] coconuts,[401] and bananas.[402] Research organizations include the Philippine Rice Research Institute[403] and the International Rice Research Institute.[404]

The Philippine Space Agency maintains the country's space program,[405][406] and the country bought its first satellite in 1996.[407] Diwata-1, its first micro-satellite, was launched on the United States' Cygnus spacecraft in 2016.[408]

The Philippines has a high concentration of cellular-phone users,[409] and a high level of mobile commerce.[410] Text messaging is a popular form of communication, and the nation sent an average of one billion SMS messages per day in 2007.[411] The Philippine telecommunications industry had been dominated by the PLDT-Globe Telecom duopoly for more than two decades,[412] and the 2021 entry of Dito Telecommunity improved the country's telecommunications service.[413]

Tourism

editThe Philippines is a popular retirement destination for foreigners because of its climate and low cost of living.[414] The country's main tourist attractions are its numerous beaches;[60]: 109 [415] the Philippines is also a top destination for diving enthusiasts.[416][417] Tourist spots include Boracay, called the best island in the world by Travel + Leisure in 2012;[418] Coron and El Nido in Palawan; Cebu; Siargao, and Bohol.[419]

Tourism contributed 5.2 percent to the Philippine GDP in 2021 (lower than 12.7 percent in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic),[420] and provided 5.7 million jobs in 2019.[421] The Philippines attracted 5.45 million international visitors in 2023, 30 percent lower than the 8.26 million record in pre-pandemic 2019; most tourists came from South Korea (26.4 percent), United States (16.5 percent), Japan (5.6 percent), Australia (4.89 percent), and China (4.84 percent).[422]

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editTransportation in the Philippines is by road, air, rail and water. Roads are the dominant form of transport, carrying 98 percent of people and 58 percent of cargo.[424] In December 2018, there were 210,528 kilometers (130,816 mi) of roads in the country.[425] The backbone of land-based transportation in the country is the Pan-Philippine Highway, which connects the islands of Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao.[426] Inter-island transport is by the 919-kilometer (571 mi) Strong Republic Nautical Highway, an integrated set of highways and ferry routes linking 17 cities.[427][428] Jeepneys are a popular, iconic public utility vehicle;[208]: 496–497 other public land transport includes buses, UV Express, TNVS, Filcab, taxis, and tricycles.[429][430] Traffic is a significant issue in Manila and on arterial roads to the capital.[431][432]

Despite wider historical use,[433] rail transportation in the Philippines is limited[208]: 491 to transporting passengers within Metro Manila and the provinces of Laguna[434] and Quezon,[435] with a short track in the Bicol Region.[208]: 491 The country had a railway footprint of only 79 kilometers (49 mi) as of 2019[update], which it planned to expand to 244 kilometers (152 mi).[436] A revival of freight rail is planned to reduce road congestion.[437][438]

The Philippines had 90 national government-owned airports as of 2022[update], of which eight are international.[439] Ninoy Aquino International Airport, formerly known as Manila International Airport, has the greatest number of passengers.[439] The 2017 air domestic market was dominated by Philippine Airlines, the country's flag carrier and Asia's oldest commercial airline,[440][441] and Cebu Pacific (the country's leading low-cost carrier).[442][443]

A variety of boats are used throughout the Philippines;[444] most are double-outrigger vessels known as banca[445] or bangka.[446] Modern ships use plywood instead of logs, and motor engines instead of sails;[445] they are used for fishing and inter-island travel.[446] The Philippines has over 1,800 seaports;[447] of these, the principal seaports of Manila (the country's chief, and busiest, port),[448] Batangas, Subic Bay, Cebu, Iloilo, Davao, Cagayan de Oro, General Santos, and Zamboanga are part of the ASEAN Transport Network.[449][450]

Energy

editThe Philippines had a total installed power capacity of 26,882 MW in 2021; 43 percent was generated from coal, 14 percent from oil, 14 percent hydropower, 12 percent from natural gas, and seven percent from geothermal sources.[451] It is the world's third-biggest geothermal-energy producer, behind the United States and Indonesia.[452] The country's largest dam is the 1.2-kilometer-long (0.75 mi) San Roque Dam on the Agno River in Pangasinan.[453] The Malampaya gas field, discovered in the early 1990s off the coast of Palawan, reduced the Philippines' reliance on imported oil; it provides about 40 percent of Luzon's energy requirements, and 30 percent of the country's energy needs.[208]: 347 [454]

The Philippines has three electrical grids, one each for Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao.[455] The National Grid Corporation of the Philippines manages the country's power grid since 2009[456] and provides overhead transmission lines across the country's islands. Electric distribution to consumers is provided by privately owned distribution utilities and government-owned electric cooperatives.[455] As of end-2021, the Philippines' household electrification level was about 95.41%.[457]

Plans to harness nuclear energy began during the early 1970s during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos in response to the 1973 oil crisis.[458] The Philippines completed Southeast Asia's first nuclear power plant in Bataan in 1984.[459] Political issues following Marcos' ouster and safety concerns after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster prevented the plant from being commissioned,[460][458] and plans to operate it remain controversial.[459][461]

Water supply and sanitation

editWater supply and sanitation outside Metro Manila is provided by the government through local water districts in cities or towns.[462][463][464] Metro Manila is served by Manila Water and Maynilad Water Services. Except for shallow wells for domestic use, groundwater users are required to obtain a permit from the National Water Resources Board.[463] In 2022, the total water withdrawals increased to 91 billion cubic meters (3.2×1012 cu ft) from 89 billion cubic meters (3.1×1012 cu ft) in 2021 and the total expenditures on water were amounted to ₱144.81 billion.[465]

Most sewage in the Philippines flows into septic tanks.[463] In 2015, the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation noted that 74 percent of the Philippine population had access to improved sanitation and "good progress" had been made between 1990 and 2015.[466] Ninety-six percent of Filipino households had an improved source of drinking water and 92 percent of households had sanitary toilet facilities as of 2016[update]; connections of toilet facilities to appropriate sewerage systems remain largely insufficient, however, especially in rural and urban poor communities.[467]: 46

Demographics

editAs of May 1, 2020, the Philippines had a population of 109,035,343.[13] More than 60 percent of the country's population live in the coastal zone[468] and in 2020, 54 percent lived in urban areas.[469] Manila, its capital, and Quezon City (the country's most populous city) are in Metro Manila. About 13.48 million people (12 percent of the Philippines' population) live in Metro Manila,[469] the country's most populous metropolitan area[470] and the world's fifth most populous.[471] Between 1948 and 2010, the population of the Philippines increased almost fivefold from 19 million to 92 million.[472]

The country's median age is 25.3, and 63.9 percent of its population is between 15 and 64 years old.[473] The Philippines' average annual population growth rate is decreasing,[474] although government attempts to further reduce population growth have been contentious.[475] The country reduced its poverty rate from 49.2 percent in 1985[476] to 18.1 percent in 2021,[477] and its income inequality began to decline in 2012.[476]

Largest cities in the Philippines

2020 Philippine census of population and housing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

| Quezon City Manila |

1 | Quezon City | National Capital Region | 2,960,048 | 11 | Valenzuela | National Capital Region | 714,978 | Davao City Caloocan |

| 2 | Manila | National Capital Region | 1,846,513 | 12 | Dasmariñas | Calabarzon | 703,141 | ||

| 3 | Davao City | Davao Region | 1,776,949 | 13 | General Santos | Soccsksargen | 697,315 | ||

| 4 | Caloocan | National Capital Region | 1,661,584 | 14 | Parañaque | National Capital Region | 689,992 | ||

| 5 | Taguig | National Capital Region | 1,261,738 | 15 | Bacoor | Calabarzon | 664,625 | ||

| 6 | Zamboanga City | Zamboanga Peninsula | 977,234 | 16 | San Jose del Monte | Central Luzon | 651,813 | ||

| 7 | Cebu City | Central Visayas | 964,169 | 17 | Las Piñas | National Capital Region | 606,293 | ||

| 8 | Antipolo | Calabarzon | 887,399 | 18 | Bacolod | Negros Island Region | 600,783 | ||

| 9 | Pasig | National Capital Region | 803,159 | 19 | Muntinlupa | National Capital Region | 543,445 | ||

| 10 | Cagayan de Oro | Northern Mindanao | 728,402 | 20 | Calamba | Calabarzon | 539,671 | ||

Ethnicity

editThe country has substantial ethnic diversity, due to foreign influence and the archipelago's division by water and topography.[278] According to the 2020 census, the Philippines' largest ethnic groups were Tagalog (26.0 percent), Visayans [excluding the Cebuano, Hiligaynon, and Waray] (14.3 percent), Ilocano and Cebuano (both eight percent), Hiligaynon (7.9 percent), Bikol (6.5 percent), and Waray (3.8 percent).[6] The country's indigenous peoples consisted of 110 enthnolinguistic groups,[478] with a combined population of 15.56 million, in 2020;[6] they include the Igorot, Lumad, Mangyan, and the indigenous peoples of Palawan.[479]

Negritos are thought to be among the islands' earliest inhabitants.[81]: 35 These minority aboriginal settlers are an Australoid group, a remnant of the first human migration from Africa to Australia who were probably displaced by later waves of migration.[480] Some Philippine Negritos have a Denisovan admixture in their genome.[481][482] Ethnic Filipinos generally belong to several Southeast Asian ethnic groups, classified linguistically as Austronesians speaking Malayo-Polynesian languages.[483] The Austronesian population's origin is uncertain, but relatives of Taiwanese aborigines probably brought their language and mixed with the region's existing population.[484][485] The Lumad and Sama-Bajau ethnic groups have an ancestral affinity with the Austroasiatic- and Mlabri-speaking Htin peoples of mainland Southeast Asia. Westward expansion from Papua New Guinea to eastern Indonesia and Mindanao has been detected in the Blaan people and the Sangir language.[486]

Immigrants arrived in the Philippines from elsewhere in the Spanish Empire, especially from the Spanish Americas.[487][488]: Chpt. 6 [489] A 2016 National Geographic project concluded that people living in the Philippine archipelago carried genetic markers in the following percentages: 53 percent Southeast Asia and Oceania, 36 percent Eastern Asia, 5 percent Southern Europe, 3 percent Southern Asia, and 2 percent Native American (from Latin America).[488]: Chpt. 6 [490]

Descendants of mixed-race couples are known as Mestizos or tisoy,[491] which during the Spanish colonial times, were mostly composed of Chinese mestizos (Mestizos de Sangley), Spanish mestizos (Mestizos de Español) and the mix thereof (tornatrás).[492][493][494] The modern Chinese Filipinos are well-integrated into Filipino society.[278][495] Primarily the descendants of immigrants from Fujian,[496] the pure ethnic Chinese Filipinos during the American colonial era (early 1900s) purportedly numbered about 1.35 million; while an estimated 22.8 million (around 20 percent) of Filipinos have half or partial Chinese ancestry from precolonial, colonial, and 20th century Chinese migrants.[497][498] During the Hispanic era (late 1700s), the tribute-census showed mixed Spanish Filipinos made up a moderate ratio (around 5 percent) of all citizens.[499]: 539 [500]: 31, 54, 113 Meanwhile, a smaller proportion (2.33 percent) of the population were Mexican Filipinos.[489]: 100 Almost 300,000 American citizens live in the country as of 2023[update],[501] and up to 250,000 Amerasians are scattered across the cities of Angeles, Manila, and Olongapo.[502][503] Other significant non-indigenous minorities include Indians[504] and Arabs.[505] Japanese Filipinos include escaped Christians (Kirishitan) who fled persecutions by Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu.[506]

Languages

editEthnologue lists 186 languages for the Philippines, 182 of which are living languages; the other four no longer have any known speakers. Most native languages are part of the Philippine branch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, which is a branch of the Austronesian language family.[483] Spanish-based creole varieties, collectively known as Chavacano, are also spoken.[507] Many Philippine Negrito languages have unique vocabularies which survived Austronesian acculturation.[508]

Filipino and English are the country's official languages.[5] Filipino, a standardized version of Tagalog, is spoken primarily in Metro Manila.[509] Filipino and English are used in government, education, print, broadcast media, and business, often with a third local language;[510] code-switching between English and other local languages, notably Tagalog, is common.[511] The Philippine constitution provides for Spanish and Arabic on a voluntary, optional basis.[5] Spanish, a widely used lingua franca during the late nineteenth century, has declined greatly in use,[512][513] although Spanish loanwords are still present in Philippine languages.[514][515][516] Arabic is primarily taught in Mindanao Islamic schools.[517]

The top languages generally spoken at home as of 2020[update] are Tagalog, Binisaya, Hiligaynon, Ilocano, Cebuano, and Bikol.[518] Nineteen regional languages are auxiliary official languages as media of instruction:[4]

- Aklanon

- Bikol

- Cebuano

- Chavacano

- Hiligaynon

- Ibanag

- Ilocano

- Ivatan

- Kapampangan

- Kinaray-a

- Maguindanao

- Maranao

- Pangasinan

- Sambal

- Surigaonon

- Tagalog

- Tausug

- Waray

- Yakan

Other indigenous languages, including Cuyonon, Ifugao, Itbayat, Kalinga, Kamayo, Kankanaey, Masbateño, Romblomanon, Manobo, and several Visayan languages, are used in their respective provinces.[483] Filipino Sign Language is the national sign language, and the language of deaf education.[519]

Religion

editAlthough the Philippines is a secular state with freedom of religion, an overwhelming majority of Filipinos consider religion very important[520] and irreligion is very low.[521][522][523] Christianity is the dominant religion,[524][525] followed by about 89 percent of the population.[526] The country had the world's third-largest Roman Catholic population as of 2013[update], and was Asia's largest Christian nation.[527] Census data from 2020 found that 78.8 percent of the population professed Roman Catholicism;[d] other Christian denominations include Iglesia ni Cristo, the Philippine Independent Church, and Seventh-day Adventistism.[528] Protestants made up about 5% to 7% of the population in 2010.[529][530] The Philippines sends many Christian missionaries around the world, and is a training center for foreign priests and nuns.[531][532]

Islam is the country's second-largest religion, with 6.4 percent of the population in the 2020 census.[528] Most Muslims live in Mindanao and nearby islands,[525] and most adhere to the Shafi'i school of Sunni Islam.[533]

About 0.2 percent of the population follow indigenous religions,[528] whose practices and folk beliefs are often syncretized with Christianity and Islam.[222]: 29–30 [534] Buddhism is practiced by about 0.04% of the population,[528] primarily by Filipinos of Chinese descent.[535]

Health

editHealth care in the Philippines is provided by the national and local governments, although private payments account for most healthcare spending.[467]: 25–27 [536] Per-capita health expenditure in 2022 was ₱10,059.49 and health expenditures were 5.5 percent of the country's GDP.[537] The 2023 budget allocation for healthcare was ₱334.9 billion.[538] The 2019 enactment of the Universal Health Care Act by President Duterte facilitated the automatic enrollment of all Filipinos in the national health insurance program.[539][540] Since 2018, Malasakit Centers (one-stop shops) have been set up in several government-operated hospitals to provide medical and financial assistance to indigent patients.[541]

Average life expectancy in the Philippines as of 2023[update] is 70.48 years (66.97 years for males, and 74.15 years for females).[10] Access to medicine has improved due to increasing Filipino acceptance of generic drugs.[467]: 58 The country's leading causes of death in 2021 were ischaemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, COVID-19, neoplasms, and diabetes.[542] Communicable diseases are correlated with natural disasters, primarily floods.[543] One million Filipinos have active tuberculosis, the fourth highest global prevalence rate.[544]

The Philippines has 1,387 hospitals, 33 percent of which are government-run; 23,281 barangay health stations, 2,592 rural health units, 2,411 birthing homes, and 659 infirmaries provide primary care throughout the country.[545] Since 1967, the Philippines had become the largest global supplier of nurses;[546] seventy percent of nursing graduates go overseas to work, causing problems in retaining skilled practitioners.[547]

Education

editPrimary and secondary schooling in the Philippines consists of six years of elementary period, four years of junior high school, and two years of senior high school.[549] Public education, provided by the government, is free at the elementary and secondary levels and at most public higher-education institutions.[550][551] Science high schools for talented students were established in 1963.[552] The government provides technical-vocational training and development through the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority.[553] In 2004, the government began offering alternative education to out-of-school children, youth, and adults to improve literacy;[554][555] madaris were mainstreamed in 16 regions that year, primarily in Mindanao Muslim areas under the Department of Education.[556] Catholic schools, which number more than 1,500,[557] and higher education institutions are an integral part of the educational system.[558]

The Philippines has 1,975 higher education institutions as of 2019[update], of which 246 are public and 1,729 are private.[559] Public universities are non-sectarian, and are primarily classified as state-administered or local government-funded.[560][561] The national university is the eight-school University of the Philippines (UP) system.[562] The country's top-ranked universities are the University of the Philippines Diliman, Ateneo de Manila University, De La Salle University, and University of Santo Tomas.[563][564][565]

In 2019[update], the Philippines had a basic literacy rate of 93.8 percent of those five years old or older,[566] and a functional literacy rate of 91.6 percent of those aged 10 to 64.[567] Education, a significant proportion of the national budget, was allocated ₱900.9 billion from the ₱5.268 trillion 2023 budget.[538] As of 2023[update], the country has 1,640 public libraries affiliated with the National Library of the Philippines.[568]

Culture

editThe Philippines has significant cultural diversity, reinforced by the country's fragmented geography.[40]: 61 [569] Spanish and American cultures profoundly influenced Filipino culture as a result of long colonization.[570][278] The cultures of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago developed distinctly, since they had limited Spanish influence and more influence from nearby Islamic regions.[53]: 503 Indigenous groups such as the Igorots have preserved their precolonial customs and traditions by resisting the Spanish.[571][572] A national identity emerged during the 19th century, however, with shared national symbols and cultural and historical touchstones.[569]

Hispanic legacies include the dominance of Catholicism[61]: 5 [570] and the prevalence of Spanish names and surnames, which resulted from an 1849 edict ordering the systematic distribution of family names and the implementation of Spanish naming customs;[208]: 75 [60]: 237 the names of many locations also have Spanish origins.[573] American influence on modern Filipino culture[278] is evident in the use of English[574]: 12 and Filipino consumption of fast food and American films and music.[570]

Public holidays in the Philippines are classified as regular or special.[575] Festivals are primarily religious, and most towns and villages have such a festival (usually to honor a patron saint).[576][577] Better-known festivals include Ati-Atihan,[578] Dinagyang,[579] Moriones,[580] Sinulog,[581] and Flores de Mayo—a month-long devotion to the Virgin Mary held in May.[582] The country's Christmas season begins as early as September 1,[583]: 149 and Holy Week is a solemn religious observance for its Christian population.[584][583]: 149

Values

editFilipino values are rooted primarily in personal alliances based in kinship, obligation, friendship, religion (particularly Christianity), and commerce.[81]: 41 They center around social harmony through pakikisama,[585]: 74 motivated primarily by the desire for acceptance by a group.[586][587][574]: 47 Reciprocity through utang na loob (a debt of gratitude) is a significant Filipino cultural trait, and an internalized debt can never be fully repaid.[585]: 76 [588] The main sanction for divergence from these values are the concepts of hiya (shame)[589] and loss of amor propio (self-esteem).[587]

The family is central to Philippine society; norms such as loyalty, maintaining close relationships and care for elderly parents are ingrained in Philippine society.[590][591] Respect for authority and the elderly is valued, and is shown with gestures such as mano and the honorifics po and opo and kuya (older brother) or ate (older sister).[592][593] Other Filipino values are optimism about the future, pessimism about the present, concern about other people, friendship and friendliness, hospitality, religiosity, respect for oneself and others (particularly women), and integrity.[594]

Art and architecture

editPhilippine art combines indigenous folk art and foreign influences, primarily Spain and the United States.[595][596] During the Spanish colonial period, art was used to spread Catholicism and support the concept of racially-superior groups.[596] Classical paintings were mainly religious;[597] prominent artists during Spanish colonial rule included Juan Luna and Félix Resurrección Hidalgo, whose works drew attention to the Philippines.[598] Modernism was introduced to the Philippines during the 1920s and 1930s by Victorio Edades and popular pastoral scenes by Fernando Amorsolo.[599]

Traditional Philippine architecture has two main models: the indigenous bahay kubo and the bahay na bato, which developed under Spanish rule.[208]: 438–444 Some regions, such as Batanes, differ slightly due to climate; limestone was used as a building material, and houses were built to withstand typhoons.[601][602]

Spanish architecture left an imprint in town designs around a central square or plaza mayor, but many of its buildings were damaged or destroyed during World War II.[603][51] Several Philippine churches adapted baroque architecture to withstand earthquakes, leading to the development of Earthquake Baroque;[604][605] four baroque churches have been listed as a collective UNESCO World Heritage Site.[600] Spanish colonial fortifications (fuerzas) in several parts of the Philippines were primarily designed by missionary architects and built by Filipino stonemasons.[606] Vigan, in Ilocos Sur, is known for its Hispanic-style houses and buildings.[607]

American rule introduced new architectural styles in the construction of government buildings and Art Deco theaters.[608] During the American period, construction of Gabaldon school buildings began,[609] and some city planning using architectural designs and master plans by Daniel Burnham was done in portions of Manila and Baguio.[610][611] Part of the Burnham plan was the construction of government buildings reminiscent of Greek or Neoclassical architecture.[608][605] Buildings from the Spanish and American periods can be seen in Iloilo, especially in Calle Real.[612]

Music and dance

editThere are two types of Philippine folk dance, stemming from traditional indigenous influences and Spanish influence.[222]: 173 Although native dances had become less popular,[614]: 77 folk dancing began to revive during the 1920s.[614]: 82 The Cariñosa, a Hispanic Filipino dance, is unofficially considered the country's national dance.[615] Popular indigenous dances include the Tinikling and Singkil, which include the rhythmic clapping of bamboo poles.[616][617] Present-day dances vary from delicate ballet[618] to street-oriented breakdancing.[619][620]

Rondalya music, with traditional mandolin-type instruments, was popular during the Spanish era.[159]: 327 [621] Spanish-influenced musicians are primarily bandurria-based bands with 14-string guitars.[622][621] Kundiman developed during the 1920s and 1930s.[623] The American colonial period exposed many Filipinos to U.S. culture and popular music.[623] Rock music was introduced to Filipinos during the 1960s and developed into Filipino rock (or Pinoy rock), a term encompassing pop rock, alternative rock, heavy metal, punk, new wave, ska, and reggae. Martial law in the 1970s produced Filipino folk rock bands and artists who were at the forefront of political demonstrations.[624]: 38–41 The decade also saw the birth of the Manila sound and Original Pilipino Music (OPM).[625][60]: 171 Filipino hip-hop, which originated in 1979, entered the mainstream in 1990.[626][624]: 38–41 Karaoke is also popular.[627] From 2010 to 2020, Pinoy pop (P-pop) was influenced by K-pop and J-pop.[628]

Locally produced theatrical drama became established during the late 1870s. Spanish influence around that time introduced zarzuela plays (with music)[629] and comedias, with dance. The plays became popular throughout the country,[614]: 69–70 and were written in a number of local languages.[629] American influence introduced vaudeville and ballet.[614]: 69–70 Realistic theatre became dominant during the 20th century, with plays focusing on contemporary political and social issues.[629]

Literature

editPhilippine literature consists of works usually written in Filipino, Spanish, or English. Some of the earliest well-known works were created from the 17th to the 19th centuries.[630] They include Ibong Adarna, an epic about an eponymous magical bird,[631] and Florante at Laura by Tagalog author Francisco Balagtas.[632][633] José Rizal wrote the novels Noli Me Tángere (Social Cancer) and El filibusterismo (The Reign of Greed),[634] both of which depict the injustices of Spanish colonial rule.[635]

Folk literature was relatively unaffected by colonial influence until the 19th century due to Spanish indifference. Most printed literary works during Spanish colonial rule were religious in nature, although Filipino elites who later learned Spanish wrote nationalistic literature.[222]: 59–62 The American arrival began Filipino literary use of English[222]: 65–66 and influenced the development of the Philippine comics industry that flourished from the 1920s through the 1970s.[636][637] In the late 1960s, during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, Philippine literature was influenced by political activism; many poets began using Tagalog, in keeping with the country's oral traditions.[222]: 69–71

Philippine mythology has been handed down primarily through oral tradition;[638] popular figures are Maria Makiling,[639] Lam-ang,[640] and the Sarimanok.[222]: 61 [641] The country has a number of folk epics.[642] Wealthy families could preserve transcriptions of the epics as family heirlooms, particularly in Mindanao; the Maranao-language Darangen is an example.[643]

Media

editPhilippine media primarily uses Filipino and English, although broadcasting has shifted to Filipino.[510] Television shows, commercials, and films are regulated by the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board.[644][645] Most Filipinos obtain news and information from television, the Internet,[646] and social media.[647] The country's flagship state-owned broadcast-television network is the People's Television Network (PTV).[648] ABS-CBN and GMA, both free-to-air, were the dominant TV networks;[649] before the May 2020 expiration of ABS-CBN's franchise, it was the country's largest network.[650] Philippine television dramas, known as teleseryes and mainly produced by ABS-CBN and GMA, are also seen in several other countries.[651][652]

Local film-making began in 1919 with the release of the first Filipino-produced feature film: Dalagang Bukid (A Girl from the Country), directed by Jose Nepomuceno.[116][117]: 8 Production companies remained small during the silent film era, but sound films and larger productions emerged in 1933. The postwar 1940s to the early 1960s are considered a high point for Philippine cinema. The 1962–1971 decade saw a decline in quality films, although the commercial film industry expanded until the 1980s.[116] Critically acclaimed Philippine films include Himala (Miracle) and Oro, Plata, Mata (Gold, Silver, Death), both released in 1982.[653][654] Since the turn of the 21st century, the country's film industry has struggled to compete with larger-budget foreign films[655] (particularly Hollywood films).[656][657] Art films have thrived, however, and several indie films have been successful domestically and abroad.[658][659][660]

The Philippines has a large number of radio stations and newspapers.[649] English broadsheets are popular among executives, professionals and students.[120]: 233–251 Less-expensive Tagalog tabloids, which grew during the 1990s, are popular (particularly in Manila);[661] however, overall newspaper readership is declining in favor of online news.[647][662] The top three newspapers, by nationwide readership and credibility,[120]: 233 are the Philippine Daily Inquirer, Manila Bulletin, and The Philippine Star.[663][664] Although freedom of the press is protected by the constitution,[665] the country was listed as the seventh-most-dangerous country for journalists in 2022 by the Committee to Protect Journalists due to 13 unsolved murders of journalists.[666]

The Philippine population are the world's top Internet users.[667] In early 2021, 67 percent of Filipinos (73.91 million) had Internet access; the overwhelming majority used smartphones.[668] The Philippines ranked 53rd on the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[669]

Cuisine

editFrom its Malayo-Polynesian origins, traditional Philippine cuisine has evolved since the 16th century. It was primarily influenced by Hispanic, Chinese, and American cuisines, which were adapted to the Filipino palate.[670][671] Filipinos tend to prefer robust flavors,[672] centered on sweet, salty, and sour combinations.[673]: 88 Regional variations exist throughout the country; rice is the general staple starch[674] but cassava is more common in parts of Mindanao.[675][676] Adobo is the unofficial national dish.[677] Other popular dishes include lechón, kare-kare, sinigang,[678] pancit, lumpia, and arroz caldo.[679][680][681] Traditional desserts are kakanin (rice cakes), which include puto, suman, and bibingka.[682][683] Ingredients such as calamansi,[684] ube,[685] and pili are used in Filipino desserts.[686][687] The generous use of condiments such as patis, bagoong, and toyo impart a distinctive Philippine flavor.[679][673]: 73

Unlike other East or Southeast Asian countries, most Filipinos do not eat with chopsticks; they use spoons and forks.[688] Traditional eating with the fingers[689] (known as kamayan) had been used in less urbanized areas,[690]: 266–268, 277 but has been popularized with the introduction of Filipino food to foreigners and city residents.[691][692]

Sports and recreation

editBasketball, played at the amateur and professional levels, is considered the country's most popular sport.[693][694] Other popular sports include boxing and billiards, boosted by the achievements of Manny Pacquiao and Efren Reyes.[583]: 142 [695] The national martial art is Arnis.[696] Sabong (cockfighting) is popular entertainment, especially among Filipino men, and was documented by the Magellan expedition.[697] Video gaming and esports are emerging pastimes,[698][699] with the popularity of indigenous games such as patintero, tumbang preso, luksong tinik, and piko declining among young people;[700][699] several bills have been filed to preserve and promote traditional games.[701]

The men's national football team has participated in one Asian Cup.[702] The women's national football team qualified for the 2023 FIFA Women's World Cup, their first World Cup, in January 2022.[703] The Philippines has participated in every Summer Olympic Games since 1924, except when they supported the American-led boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics.[704][705] It was the first tropical nation to compete at the Winter Olympic Games, debuting in 1972.[706][707] In 2021, the Philippines received its first-ever Olympic gold medal with weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz's victory in Tokyo.[708]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Although the Flag and Heraldic Code of the Philippines (Republic Act 8491) passed in 1998 defined modifications to the coat of arms that removed the colonial charges, a referendum legally required to ratify the changes has not yet been called.

- ^ While Manila is designated as the nation's capital, the seat of government is the National Capital Region, commonly known as "Metro Manila", of which the city of Manila is a part.[2][3] Many national government institutions are located on various parts of Metro Manila, aside from Malacañang Palace and other institutions/agencies that are located within the Manila capital city.

- ^ As per the 1987 Constitution: "Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis."[5]

- ^ a b Excludes Catholic Charismatics numbering 74,096 persons (0.07% of the Philippine household population in 2020)[7]

- ^ a b The actual area of the Philippines is 343,448 km2 (132,606 sq mi) according to some sources.[209]

- ^ See Date and time notation in the Philippines.

- ^ /ˈfilɪpiːnz/ ; Filipino: Pilipinas, Tagalog pronunciation: [pɪ.lɪˈpiː.nɐs]

- ^ Filipino: Republika ng Pilipinas.

In the recognized regional languages of the Philippines:- Aklan: Republika it Pilipinas

- Bikol: Republika kan Filipinas

- Cebuano: Republika sa Pilipinas

- Chavacano: República de Filipinas

- Hiligaynon: Republika sang Filipinas

- Ibanag: Republika nat Filipinas

- Ilocano: Republika ti Filipinas

- Ivatan: Republika nu Filipinas

- Kapampangan: Republika ning Filipinas

- Kinaray-a: Republika kang Pilipinas

- Maguindanaon: Republika nu Pilipinas

- Maranao: Republika a Pilipinas

- Pangasinan: Republika na Filipinas

- Sambal: Republika nin Pilipinas

- Surigaonon: Republika nan Pilipinas

- Tagalog: Republika ng Pilipinas

- Tausug: Republika sin Pilipinas

- Waray: Republika han Pilipinas

- Yakan: Republika si Pilipinas

In the recognized optional languages of the Philippines:

- ^ This is a summary, omitting significant detail. For more detail, see Schurman Commission § Survey visit to the Philippines.

References

edit- ^ Republic Act No. 8491 (February 12, 1998), Flag and Heraldic Code of the Philippines, Metro Manila, Philippines: Official Gazette of the Philippines, archived from the original on May 25, 2017, retrieved March 8, 2014

- ^ Presidential Decree No. 940, s. 1976 (May 29, 1976), Establishing Manila as the Capital of the Philippines and as the Permanent Seat of the National Government, Manila, Philippines: Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, archived from the original on May 25, 2017, retrieved April 4, 2015

- ^ "Quezon City Local Government – Background". Quezon City Local Government. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "DepEd adds 7 languages to mother tongue-based education for Kinder to Grade 3". GMA News Online. July 13, 2013. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Article XIV, Section 7". Constitution of the Philippines. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 1987. Archived from the original on June 9, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". Philippine Statistics Authority (Press release). Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Mapa, Dennis (February 21, 2023). "Religious Affiliation in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority (Press release). p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ "Philippines country profile". BBC News. December 19, 2023. Archived from the original on December 19, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "Philippines". Central Intelligence Agency. February 27, 2023. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2023 – via CIA.gov.

- ^ a b c d e "Philippines". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. June 7, 2023. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ "Philippines". June 7, 2023. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ "Population Projection Statistics". psa.gov.ph. March 28, 2021. Archived from the original on December 26, 2023. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Mapa, Dennis S. (July 7, 2021). "2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH) Population Counts Declared Official by the President" (Press release). Philippine Statistics Authority. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Philippines)". International Monetary Fund. April 16, 2024. Archived from the original on April 16, 2024. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ "Highlights of the Preliminary Results of the 2021 Annual Family Income and Expenditure Survey" (Press release). PSA. Archived from the original on May 16, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. March 13, 2024. p. 289. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Philippine Yearbook (1978 ed.). Manila, Philippines: National Economic and Development Authority, National Census and Statistics Office. 1978. p. 716. Archived from the original on March 6, 2023. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-135-4. Archived from the original on February 3, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Malcolm, George A. (1916). The Government of the Philippine Islands: Its Development and Fundamentals. Philippine Law Collection. Rochester, N.Y.: Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company. p. 3. OCLC 578245510. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Spate, Oskar H.K. (November 2004) [1979]. "Chapter 4. Magellan's Successors: Loaysa to Urdaneta. Two failures: Grijalva and Villalobos". The Spanish Lake. The Pacific since Magellan. Vol. I. London, England: Taylor & Francis. p. 97. doi:10.22459/SL.11.2004. ISBN 978-0-7099-0049-8. Archived from the original on August 5, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Tarling, Nicholas, ed. (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Vol. 2: From c. 1500 to c. 1800. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-521-66370-0. Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "The 1899 Malolos Constitution". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines (in Spanish and English). Título I – De la República; Articulo 1. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2023.